Suggested Topics :

'Unmechanical: Ritwik Ghatak in 50 Fragments': A Document of Revolutionary Imagination

Long before parallel cinema became fashionable, Bengali auteur Ritwik Ghatak proposed a film about Vietnam shot entirely in Bengal. This 1968 essay reveals the vision of the director who changed Indian cinema.

This year marks the birth centenary of Ritwik Ghatak, the Bengali filmmaker whose explorations of Partition trauma, social realities and working-class struggle established him as one of Indian cinema’s great auteurs.

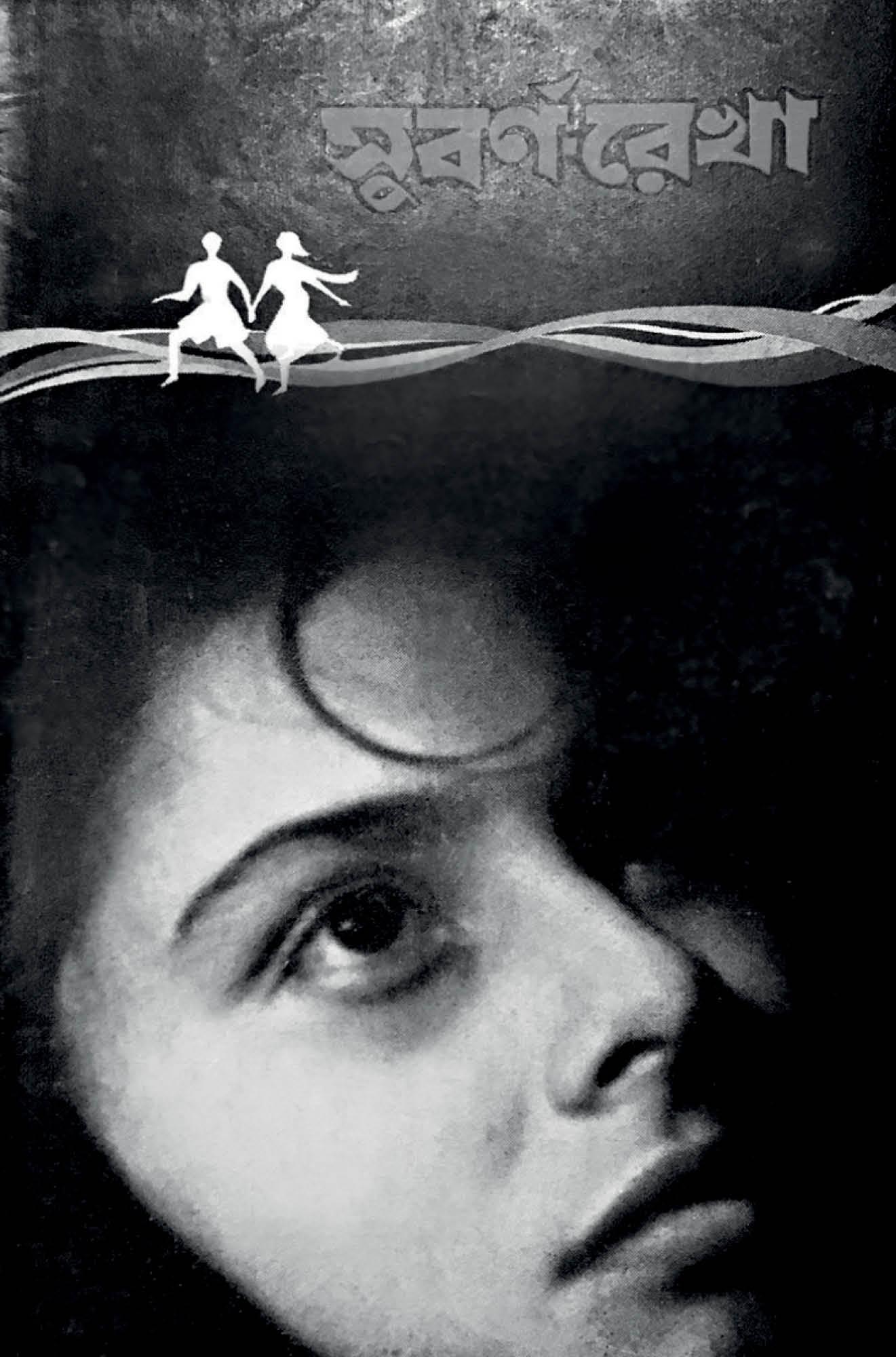

Best known for works such as his trilogy on the Partition — Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), and Subarnarekha (1965) — he influenced everyone from Satyajit Ray to Mani Kaul. To celebrate his centenary, Westland Publications has released Unmechanical: Ritwik Ghatak in 50 Fragments, edited by sports journalist Shamya Dasgupta, bringing together artistes, academics, actors and journalists writing about their encounters with the director. These 50 essays celebrate Ghatak through reflections and expressions of love.

The following essay — written by Ghatak in 1968 — outlines his vision for a film about Vietnam that would be shot entirely in Calcutta (now Kolkata), connecting the American War in Southeast Asia to the struggles of Bengal’s impoverished. The film was never made, but the essay remains a document of revolutionary imagination.

Edited excerpt from the book:

The Film I Want to Make About Vietnam

RITWIK GHATAK

The idea of making a film about Vietnam is a particularly difficult — and intensely sacred — one for any film director today. Tossing off a casual remark on the subject without going deep into the matter, or before examining the complete information on Vietnam, is either insanity or travesty. It is this travesty that I have to commit now.

My knowledge of Vietnam runs only as far as newspapers, some photographs and analyses of the news in a few magazines go. Leave alone Vietnam, I haven’t ever been anywhere in Southeast Asia. So, when it comes to the source of Vietnam’s abundant spirit of life, I can only discuss it at my desk, I cannot capture its pulse. Still, somewhere, somehow, I have been given an indication that this is an event that will change the pages of history. In some way, it seems to me, Vietnam will profoundly change something for the world.

One more thing. To make a film, I have to be confined to Calcutta or to Bengal. Not only do I not think of this as a problem, but, on the contrary, it also signals the shining possibility of being a primary condition for creative art.

From the perspective of what little I have perceived of Vietnam, the battle there is also our battle. The same struggle is being waged here. Vietnam is the symbol of resistance against all kinds of oppression in today’s world. Actually, terming it a symbol would be wrong; it is the most extended form of this resistance. The suffering and tears in our own country are extensions of the Vietnam War. American imperialists have not understood this, which is why Vietnam has stunned them. Or, one might say, turned them into mad dogs.

I’m told that some film-makers in a country across the seas are planning films on Vietnam, and some have even made them. I’m not talking here about documentary journalists, who have presented with great power the visible war in Vietnam. I’m referring to those in a distant country, who are trying to participate in Vietnam on the strength of their brains alone. In my opinion, they are bound to fail. I have had the fortune of watching a film on Hiroshima made by someone from this class of directors. This is the film that has led me to such a conclusion.

I recall something else as well. A renowned French director has expressed a desire to make a film on Vietnam. Several years ago, he had been given a proposal to make a film on Napoleon’s life. Not the Napoleon of the battlefield, he had said then, nor the wars themselves—what had appeared more meaningful and artistically inspiring to him was the couch on which Napoleon had sex with women. He would begin his film with this couch. I tremble at the very thought of what might ensue if Vietnam were to fall into the hands of such people.

For, given its involvement with many other things, Vietnam has also turned into something else that’s lethal — fashionable. So-called intellectuals have begun to jump up and down about Vietnam. They will never be able to grasp Vietnam’s tears of blood, and its resolve tempered in fire. Because, just like the American imperialists, they can never place their fingers on Vietnam’s pulse. Like ikebana or terracotta horses, their study of Vietnam allows them to remain ‘ultra-modern’. Even amidst all of this, they might manifest the terrifying tendency of being caught up in so-called human relations. May god bless them.

Now let me consider how I would move forward with my own film. These are, of course, entirely disorganised thoughts.

A Calcutta slum.

A hideously ugly room.

A mother, with her sick child beside her. A voice outside. The mother pours out some hooch from a pot in the corner and takes it out.

The sick child cries.

Outside, smoke rises from a freshly lit clay oven. The mother offers the bowl of hooch to a man.

A police whistle drowns the cries of the child. Several people run up and surround them.

Police whistles … the child’s crying …

The sound of a rocket whistling upwards.

An American bomber plane. Split into two halves mid-air. About to plunge to the ground. (Seen in a still image, of course, for I always want to present the real war in Vietnam through stills. I will modulate these to the rhythms of living, moving images of the country.)

With this beginning, I want to show the helpless crimes of the impoverished in our country, which we normally avoid when we give the fighting spirit of the common people a stylish appearance for public presentation. I will reveal the entire picture of reality—the causal relationships between these so-called crimes, which are the lowest expression of the harsh realities of our fighting masses. The images of Vietnam will accompany them as explanation.

Then I will move to another episode, where I will depict the dreams of the downtrodden as just that — dreams. These segments will be based entirely on music and partly on dance. I will make no reference to reality here. As punctuation, there will be a succession of images of the brave girls and boys of Vietnam and of Algeria’s National Liberation Front. As though they are determined to ensure that these dreams materialise. I will end this episode with a scene of musical joy and exuberance, with thousands of tender young children dancing. Their dancing and freedom fighters leaping over trenches will be choreographed to the same rhythm.

Now to the final episode. Here I will emphasise the presentation of the people as fighters. There will be full-throated recitations of Ho Chi Minh’s poetry in translation, and scenes of the buoyant accomplishments of the combating and toiling masses will flow past our eyes. This ebullience is the elation of fulfilling the dreams presented in the previous episode.

Here I will try to capture that very pulse of life, which is a mystery to oppressors. The same survival spirit that sends roots into the earth and absorbs nutrition from it, the same survival spirit that is born in hard steel and the sweat of the body, the same survival spirit that exists in the depths of meditation — where there is profound peace — I will try to give it shape in the film.

I do not know if I will succeed, but I will try.

This is how I will end my film.

A young man who has been shot. Maybe a student, maybe a peasant. His agonised but elated screams will be borne to us, and he will collapse. Even in the face of death, he will clutch the earth with both his hands. My camera will go beyond his hands to his clotted blood — which the earth sucks in.

Another Vietnam is being born there. A Vietnam that is immortal.

This essay was originally published in Anandabazar Patrika in 1968.

Translated by Arunava Sinha; Introduction text by Prathyush Parasuraman.

Arunava Sinha translates classic, modern and contemporary fiction, non-fiction and poetry from Bengali and Hindi into English, and fiction and poetry from English and Hindi into Bengali. Over ninety-five of his translations have been published globally so far. He teaches at Ashoka University, where he is also the co-director of the Ashoka Centre for Translation, and is the books editor at Scroll.in.

To read more exclusive stories from The Hollywood Reporter India's December 2025 print issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest book store or newspaper stand.

To buy the digital issue of the magazine, please click here.