Suggested Topics :

From 'Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3' to 'Barzakh': The Range of Queer Desire on Screen in 2024

The revelation of queerness, is the revelation of desire, but more importantly in these stories, it is the promise of trauma and conflict

It is easy to believe, watching Hindi cinema and streaming in 2024, that queerness is always a revelation. It is impossible that it exists lightly on the surface of the story — it has to not just be stated, but its stakes have to be laid out, too. The revelation of queerness, is the revelation of desire, but more importantly in these stories, it is the promise of trauma and conflict.

In Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3, Waack Girls, and Big Girls Don’t Cry, parental or societal disgust and queer assertion come in the same breath. In Waack Girls, we find out that Lopa Mehta (Rytasha Rathore), the lesbian daughter of a rich contractor is “a proud member of the queer community and a hater of oppression,” in the very same inch of a sentence where we register her parents’ disapproval — they know of their daughter’s desires, they know they cannot do anything about it, and they make an expression of having sniffed rotten eggs. Over the course of the season, Lopa’s relationship with her lover withers, and her antagonism towards her parents intensifies — for reasons entirely unrelated to her queerness — and the parental opposition to queerness is replaced by the parental opposition to her career choices. The parent is no longer a figure that needs to make that arc from being ashamed to beaming pride, but, instead, from being ashamed into the full garb of stock villainy, as though the show lost sight of its own stated drama.

With Big Girls Don’t Cry and the blockbuster film Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3, to give a character queerness, is not to give them desire, but to give them conflict. In Big Girls Don’t Cry, a character nonchalantly brings up the question of when her brother is coming out to his parents as a “ten-on-ten homo” — again, her brother’s sexuality and the anxiety about parent’s approval comes as one moment, inseparable almost. Very rarely is queerness a moment that floats into the story — like the final kiss in Citadel: Honey Bunny, that the ruthless agent KD (Saqib Saleem) plants on the lips of a lover, his right-hand-man, lying dead. His assertion of grief and queerness emerges together, a moment that neither expands nor digs — KD’s queer desire is not addressed before or since, but its possibilities lurk, much like the suspicious, unstated affair that the brother and husband of Bae (Ananya Panday) are having on the sidelines of Call Me Bae.

Big Girls Don’t Cry does not have, nor aims for that cavalier vocabulary. One of the central thrusts of the show is Leah (Avantika Vandanapu), the star basketball player, who is in love with Vidushi (Himanshi Pandey), her junior — a girl who is more forceful and honest about her desires, as she is about her butch appearance. Their love is this conflict. “Whatever we have off-court, stays off-court,” Leah tells Vidushi. The arc of the show is Leah’s friends pushing her to accept herself, and feel pride, in one climactic gesture of singing protest against the school authorities.

This is the itch with the “pride” discourse that ties itself to the ethical demands of “representation”. It is so narrow, it almost defeats its own purpose. Because if pride is where you want to end up, shame, inevitably, is where you begin. Their relationship to queerness begins as one of guilt. Even pleasure is tainted by an impending punishment — the girls will kiss only so that they get caught and suspended; Kartik Aryan’s character will dance in Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3, in kathak regalia, as a woman, only to be caught and have his body burnt as punishment. To see characters pursue pleasure is to see them play with fire, a promise of doom.

As anyone who wrestles with queerness knows, pride and shame are not opposites; they exist alongside each other, and that is our cross to bear. You can spend weeks in the comfort of familial acceptance, but one invasive and suspicious gaze can tumble the whole house of cards. The question is not how pride can obliterate shame, but how uncomfortably can they exist together. But these stories are uninterested in queer desire, seeing queerness, like how cinema sees class and caste, as solely a site of conflict.

Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3’s “revelation” of Manjulika being a man (Aaryan) who yearns to be seen, to identify as a woman, unsteadies this neat demand for representation. It is impossible to know if the film — by making the transgender woman coming out as a plot twist — is making fun of it or yearning to be sensitive about it. Especially in a year in which Madgaon Express had an extended gag about men dressed in navaris, the very image of a man dressed as a woman coming out of left field, is one that is consumed, primarily, as shock, a shock that gets lubricated with humour. Aryan’s awkward performance and ill-stitched look are so strange and stiff, the audience I was watching the film with broke out in peals of laughter — and it is a fragile moment, because you do not know if what is being laughed at is the idea of being a woman or the lead-footed performance. It is one of those unsettling moments when you do not know how to enter the film, because the film’s surface has rendered itself both alluring and opaque.

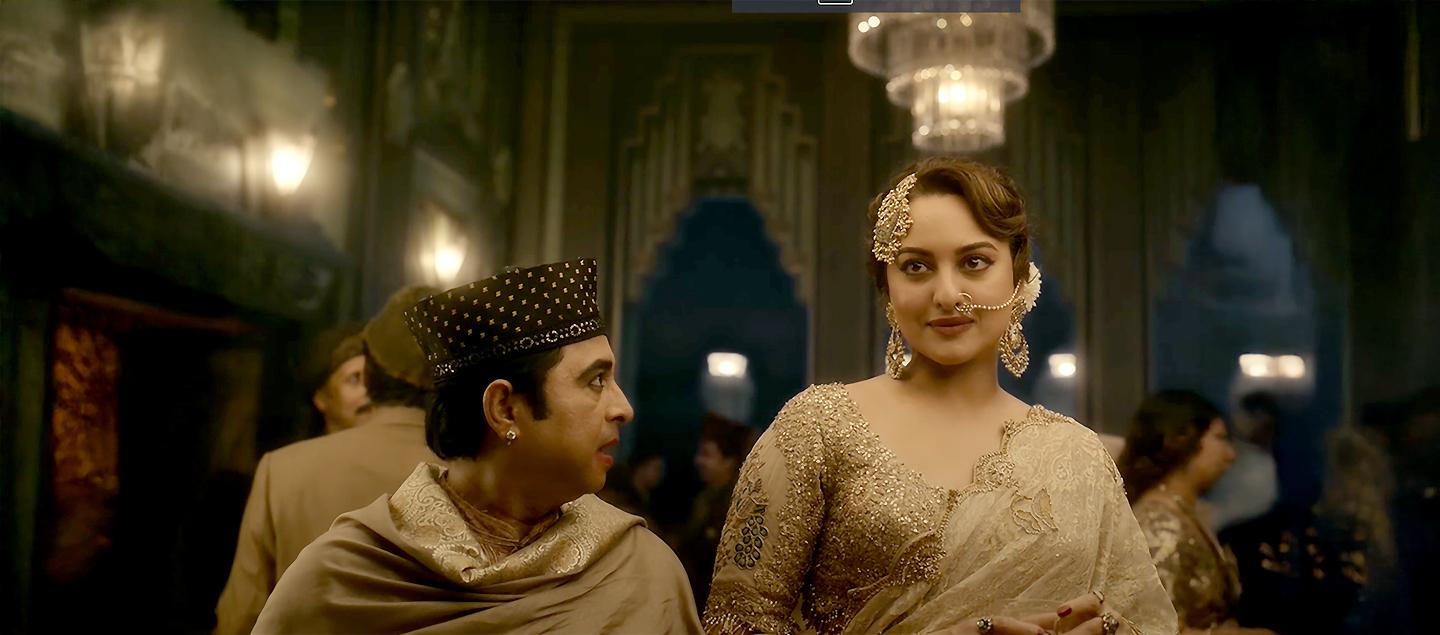

Then, there is the gay ustad of Heeramandi (Indresh Malik) who gives gossip in return for a night well spent in the arms of the beefy Cartwright (Jason Shah), and Fareedan (Sonakshi Sinha) whose rejection of men is so total, that she is a lesbian — a political lesbian, as the second wave feminists would say. Maybe that is what camp offers — a reprieve from these questions, from these demands that representation makes on cinema, because it makes fragile the question of good and bad representation, for what you see has no relationship to who you are, so elevated is its pitch of storytelling, so perfume-like its characters, they just as easily slip into the shadows as they shimmy in the spotlight.

If queerness is a revelation, it is also a wrinkle that needs to be resolved. It is not the queer character who gets the arc, but queerness itself as an idea that gets an arc, from being caged to being celebrated, footloose, and by being celebrated being resolved. The sweet, but clumsily constructed segment of trans lovers in Love Storiyaan does not even have the language to see their love as outside this neat arc. The queer character, then, is a mere vessel for this arc. On the other hand, the camp presentation of queerness sees it as a perfunctory, quirky detail to push the story forward.

But to take queerness seriously, or at least sensually, you must take queer desire seriously, sensually — and neither of the two paths stated above take queer desire seriously. The way Barzakh, on the other hand, holds its camera on a man sucking on a mango, the pink lips, bordered by a neat moustache or the arch of the lower back, with the cut of each muscle flexed and flayed into existence — these are images of heat, singeing the eyes of the spectator with desire. They allow the audience to see the man the way the lover would.

That we are drawn to each other not because we want to fight the system, but because in order to love, incidentally, the system must be fought. Somewhere along the line, though, our stories seem to have swapped the latter for the former.