Suggested Topics :

From Mandira Bedi to Shibani Akhtar, How Female Anchors Changed Cricket in India

Before cricket became a billion-dollar entertainment juggernaut, the televised world was an all-male realm. And then, match after IPL match, women commentators found a voice.

In the early 2000s, when cricket broadcasting in India was still a man’s domain, Mandira Bedi stepped onto the studio floor as the host of Extraaa Innings during the 2003 ICC World Cup and became one of the most recognisable faces on television — and also one of the most polarising.

In the years before cricket became a billion-dollar entertainment juggernaut, the sport’s televised world was a cloistered space that was dominated by men, insulated from change, and sceptical of outsiders. Especially if the outsider wore noodle straps.

Best known then as a television actress, Sony signed on Bedi to host Extraaa Innings, a studio show designed to add flair to cricket coverage. But her presence ignited a fierce backlash.

“People were just not ready,” says Suprita Das, a senior sports journalist and author of the book, Free Hit: The Story of Women’s Cricket in India. “And by people, I also mean her colleagues on the panel, who were all men. They just didn’t believe it was her space to be in. If she hadn’t played cricket, then what was she doing there?”

Critics were quick to label Bedi “an airhead”. Her contributions were dismissed, her role trivialised as “the extra in Extraaa Innings”. What she wore became a national talking point. “There was so much commentary and criticism about who she was, what she was wearing, what she wasn’t wearing,” Das tells The Hollywood Reporter India. “What did she do to deserve that place on a cricket World Cup panel with eminent cricketers?”

Bedi, as Das documented in her reporting and interviews, prepared rigorously — she would print out statistics and data in the hotel’s business centre, and would study the game late into the night. But little of that mattered. “She told me she used to go to bed crying every night,” Das recalls. “She felt miserable. She gave it her best, but it was never enough.”

Why is She Here?

To understand the extent of Bedi’s disruption, one must first understand the landscape she entered. “It wasn’t a space for women. As simple as that,” Das says. “Even if no one said it aloud — and by no one, I mean middle-aged male cricket journalists — you didn’t need them to say it. You could feel it. The undertone was always: Why is she here?”

Female sports reporters were few and far between, especially in print. Those who did make it into the press box often found themselves alone. “You always had to prove yourself,” says Das. “You had to work two or three times harder, just to be taken seriously.”

As television news boomed in the early 2000s, more women entered sports journalism as anchors, correspondents and field reporters. But even that visibility came at a cost. “There was always this impression from senior print journalists that the ‘TV girls’ didn’t really know much,” Das says. “That they were just pretty faces saying something on camera.”

Resentment sometimes followed when these women landed interviews or scoops with Indian cricketers because access was rare and coveted. “The belief was they got those stories because they were women,” says Das. “Because of how they looked, or dressed, or spoke.” Dressing, in particular, was fraught with implication. “Of course, the noodle straps became a thing which Mandira was trolled for,” says Das.

Sports commentator and broadcaster Mayanti Langer Binny remembers the last time she went viral. It wasn’t for an interview or a post-match insight. It was because she and her co-commentator were wearing matching clothes. A woman presenter’s outfit often garners more attention than her insights. Viewers scrutinise her appearance, reducing her credibility to her clothing choices. This persistent focus on style over substance reinforces the idea that women must first look the part before they’re allowed to be heard. “I joke with my stylist every tournament — I’m like, ‘If I don’t become a meme, am I even successful’?” Binny tells The Hollywood Reporter India. “You have to laugh at yourself. You can’t survive in this industry without that.”

Today, Binny is one of the most recognisable faces in Indian sports broadcasting — a fixture on screens during marquee cricket tournaments, and a voice that fans associate with high-stakes matches. “Over the years, I’ve gone from being the only girl in the room, to witnessing more and more women come in — behind the camera, from production, from marketing. Now we often shoot programming where the floor manager is a woman, the production manager is a woman, the host is a woman, the producer is a woman. That’s really heartening,” she says.

Today, women occupy a far more visible space in cricket broadcasting and journalism. Yet, many of the early dynamics — the scrutiny, the need to justify one’s presence — persist in subtler forms.

When former England cricketer Isa Guha appeared as a guest panellist during an early season of the Indian Premier League, her credentials were impeccable: a fast-bowling all-rounder, a two-time World Cup winner, and a prominent voice in the commentary box globally. But none of that seemed to matter once the cameras rolled. “I remember the other people in the studio, including a host and former cricketers, just continuously went on talking about how great she looked — about her glowing skin, her outfit, how she looked in it,” recalls Das. “You could see on her face that she was really not comfortable in that space.”

This discomfort wasn’t an anomaly. Women who came before Isa Guha were routinely subjected to the same patronising treatment. The go-to excuse was always the same: “She didn’t play cricket, so why should she talk about it?” But Guha’s experience exposed a harsher truth. Even women who have played cricket at the highest level are not spared the sexist scrutiny. “She was complimented heavily for how attractive she was... without acknowledging the fact that she’s a two-time World Cup winner who’s here to offer cricketing knowledge and acumen,” Das says. “That’s misogyny. Plain and simple,” says Binny. “The trolling I’ve received over the years has had very little to do with my cricket knowledge,” she says. “And the one thing that still upsets me is when players’ partners are made scapegoats after bad performances. That’s still happening.”

Breaking In, Breaking Through

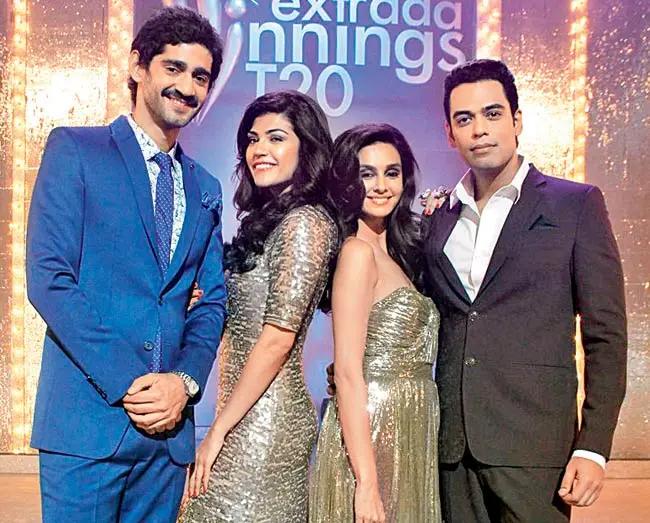

The presence of women in cricket broadcasting has had ripple effects across the ecosystem — far beyond what many initially imagined. As networks expanded coverage of live sports, women entered not just as anchors and reporters, but across production, marketing, scripting and digital strategy. The shift was visible on screen, but just as vital behind it. Shows like Extraaa Innings T20 altered the viewing experience itself.

The studio show blended expert analysis with sharp commentary. It wasn’t focused singularly on breaking down technique and economy rates; the discussions were more candid and more accessible. “Ultimately, it opened the doors for people who weren’t necessarily hardcore cricket fans but could still enjoy the game by watching with those who were,” says Shibani Dandekar Akhtar, producer, presenter, actress, and singer. “Extraaa Innings T20 brought a different flavour to the IPL compared to what we see now, which leans more toward a traditional sports journalism approach. Extraaa Innings added an element of entertainment, making the tournament more engaging,” Akhtar adds.

What that did was widen the lens of who cricket was for. By consciously creating programming that didn’t only cater to purists or one narrow demographic, broadcasters invited in a broader audience. “You can’t have a successful show if you only cater to one crowd,” says Akhtar. While cricket coverage still overwhelmingly caters to men — and the male gaze remains inescapable — accessible, personality-driven journalism around the sport helped expand its cultural reach. More women began watching, engaging, and eventually working in the ecosystem. According to latest data from the Broadcast Audience Research Council (BARC), there was a 21% growth in female viewership in IPL in 2020 from 2019; and TVRs increased 5.4 from 4.3. What started as entertainment coverage ended up redrawing the edges of who felt welcome in the conversation.

Claiming Space, Making Space

Another entirely unexpected shift was documented by Das in Free Hit: The Story of Women's Cricket in India. Once Mandira Bedi found herself at the Cricket Club of India in Mumbai, where she witnessed the Indian women’s cricket team play an international match in front of fewer than 50 spectators — mostly families and officials. She was stunned. She sought out Shubhangi Kulkarni, then secretary of the Women’s Cricket Association of India, and offered to help. Within days, she introduced Kulkarni to executives at Asmi, a diamond jewellery brand for which she was a brand ambassador. The company agreed to sponsor the team — periodically, and with no more demand than having their logo appear during televised games. It was, Das writes, “an offer difficult to refuse”.

Bedi’s involvement deepened. She met with Jagmohan Dalmiya, then president of the BCCI, urging institutional support. She turned up for the team’s Asia Cup matches in Sri Lanka in 2004. Kulkarni later learned that Bedi had declined a reported ₹10 lakh fee for an Asmi campaign — directing the money instead to women’s cricket. In a sport that rarely made room for its women, Bedi found a way in and left the door open behind her.

Inside stadiums, progress often stalls at the most basic level — access to clean toilets, ramps, elevators, and safe spaces for working professionals. “I’ve worked with women producers who were afraid to use the facilities, so they’d go the whole day without drinking water,” says Binny. “When I started 19 years ago, there were no facilities for women. No one even thought to open a women’s bathroom for the one female presenter on the crew.” She’s heard of athletes changing in makeshift offices or men’s locker rooms because no one designed the space with them in mind. “Even women sportspersons in different parts of India often don’t have proper dressing rooms… These are oversights. But they matter,” she asserts.

Binny, one of cricket’s most sought-after presenters, now uses the very access she’s earned to point out the spaces the sport still overlooks. In Lucknow recently, she noticed wheelchair access had been added to a stadium. “That’s a whole section of fans we usually don’t think about,” she says. But gestures like these remain exceptions, not the norm. “If you don’t have basic facilities in a stadium, how can people enjoy it?” she asks. “If you’re bringing young children, how do you expect them to use toilets that aren’t clean? These are small things, but they make the biggest difference.”

When asked whether women have truly benefited from the changing ecosystem, her answer is unequivocal: “Cricket is such an amazing platform because it’s loved and highly watched. Sure, there’s scrutiny — you’re judged constantly. But the flip side is that you’re given an incredible opportunity.”

For Binny, visibility is only meaningful when it cuts across expectation. “I get young men telling me they look up to me as an anchor, and young women saying my colleague Jatin [Sapru] is their inspiration,” she says. “It’s not gender-specific anymore. That’s a good thing.”

The next generation, she believes, is stepping into the spotlight with a kind of sure-footedness she never had the luxury of. “The girls I work with now are aware of the scrutiny, and they’re ready for it,” she says. “They work hard at their craft. They’re sharp. They know what they’re doing.”

Even the audience, once quick to second-guess a woman with a mic, is learning to listen. “It’s not, ‘oh, she’s a girl talking about cricket’. Now you’re judged on your presentation, your knowledge — and that’s a great step forward.” Still, Binny carries the weight of being among the first women in this field. “My job is to be diligent, to honour the space I work in and the people I work with,” she says. “And now… if I get trolled for matching clothes, that’s fine. I’ve made peace with that.”

Cricket today looks a little different than it did a generation ago. Equal representation is still far from being a reality, but it’s been tilted — just enough — for women to find a foothold. People like Mandira Bedi, Mayanti Langer Binny, and Shibani Dandekar Akhtar walked into a closed room, took up space, and made space for everyone else.