Suggested Topics :

How Theatrical Re-releases of Old Films Are Granting Them New Lease of Life

The Hollywood Reporter India explores the future of Indian cinema with actor R. Madhavan, and producers Sohum Shah and Siyad Kokker, following the promising turnout at the recent re-releases of their old films.

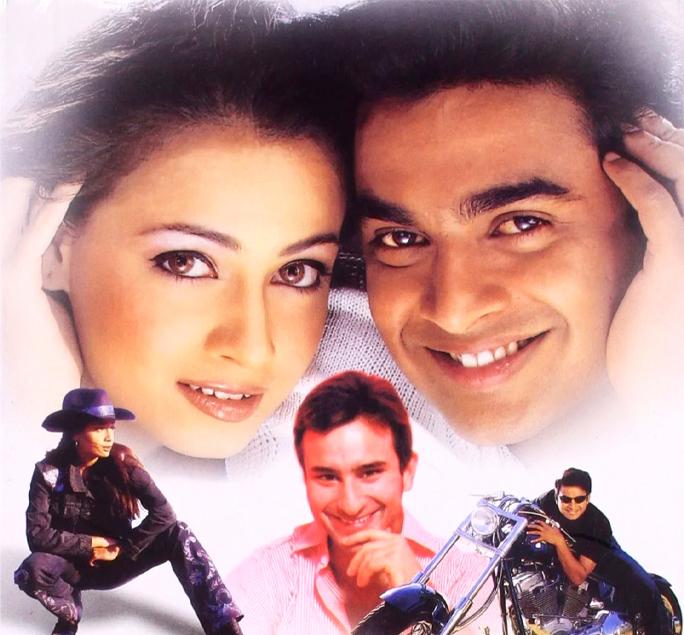

LAST UPDATED: NOV 08, 2024, 11:31 IST|6 min readNostalgia is driving India’s box office in 2024, with cult favourites like Rockstar (2011), Veer-Zaara (2004), Spadikam (1995) and Laila Majnu (2018) drawing fans back to the big screen. “It’s baffling yet extremely flattering to see audiences repeating dialogues and dancing to the songs again in theatres, screaming and cheering before lines are even spoken,” says R. Madhavan, whose Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein (2001) is among the latest films to have experienced a re-release.

The intriguing bit, however, is the resurgence of films that had initially flopped. While Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein (2001), along with the likes of Tumbbad (2018) and Devadoothan (2000), had their loyal fanbases, they didn’t achieve significant box-office success at the time. This begs the question, how are they thriving — or even outperforming new releases — today? Is that genuinely granting the actors and filmmakers a second chance?

Resurrecting the Box Office

Tumbbad is one such film that did, in fact, outperform a new release the day it returned to theatres. As the first Indian film to open the Venice International Film Critics’ Week in 2018, it came with high expectations that were not met, says actor and producer Sohum Shah. Reflecting on those difficult times, he says: “I was shocked when I saw the numbers for the first two days; my heart broke. I remember calling my brother and telling him that I failed.” While Shah did receive messages of support from fellow filmmakers Shakun Batra and Abhishek Kapoor, his disappointment was profound, especially since Tumbbad was a film six years in the making.

Interestingly, whenever Shah would post on social media, even years after the film’s release, his inbox would be flooded with two recurring questions: when is he re-releasing Tumbbad, and if he has begun working on the sequel? “Nobody ever just complimented my watch, spectacles or clothes,” he says with a laugh. Despite the disheartening outcome during the initial release, Shah remained optimistic; in his own words: “If one isn’t, they can't survive in a city like Mumbai!” It paid off in a remarkable turn of fate, when the box-office numbers from the re-run matched his original expectations.

With the ticket affordably priced at about ₹150 each, the high turnout for Tumbbad’s re-release is a testament to its massive footfall. Shah credits its renewed success to the evolving landscape of Indian cinema. “Post the COVID-19 pandemic, our audience has been exposed to different kinds of cinema, and their perspective has changed,” he says. “In fact, during the re-release, my brother asked me if I had changed anything in the film, because he liked it so much more this time! In 2018, people were used to watching formula-based films. But the Indian landscape has changed a lot since. For example, students have access to world cinema and cultures abroad.”

R. Madhavan, on the other hand, knew then what we know now — that Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein is an exceptional film that audiences across generations will relate to over the years. “We had broken the rules of storytelling. It had worked brilliantly in Tamil, and I was sure that it would do so in Hindi as well. But the outcome surprised me,” he says. However, he adds, “I wasn’t as disappointed as I should have been, as one is expected to be when one of their first films flops.” Because, at some level, he knew that Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein had a long shelf life.

But Madhavan was sceptical about re-releasing the film. “It had been 23 years [since its release], and the film has played on at least one television channel twice a week since. It’s available on OTT [platforms] and YouTube with multiple channels and college events featuring its songs, snippets and dialogues,” he says. He was uncertain about how it would be received in theatres, though he did suspect it would be a novel experience, like a trip down memory lane. And he wasn’t wrong. Today, Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein has arguably garnered a cult following, and while that’s not surprising for the actor, “it still feels great to be proven right!” he says. His social media has been bombarded with love for his character, Maddy, once again after all these years.

One of the biggest film re-releases in the history of Indian cinema, however, was that of Amitabh Bachchan’s Sholay (1975). And the man behind that move was filmmaker, producer, film archivist and restorer, Shivendra Singh Dungarpur. He's also the founder and director of the Film Heritage Foundation, a Mumbai-based not-for-profit organisation set up in 2014, which supports the conservation, preservation and restoration of the moving image, along with developing interdisciplinary educational programs. “I watched films with awe when I was a kid. I used to write letters to the film stars, talk to the people on screen. They defined my life,” he says.

But after the COVID-19 pandemic, when the audience began gravitating more towards streaming platforms online, Dungarpur decided to bring them back to the screens. With that in mind, his foundation curated Bachchan: Back to the Beginning in 2022 — a festival celebrating Amitabh Bachchan’s 80th birthday by showcasing his landmark films from the ’70s and the ’80s. “I wrote to Mr. Bachchan telling him that I wanted to screen his films, to which he said, ‘Screen my contemporary films, not the ones that are 50 years old.’” But Dungarpur knew that when people would see some of the most popular films of a bygone era back in theatres, they would come. “I realised I must do it at the PVR chain, because they are like McDonald's, right? They’re in every nook and corner.” The idea paid off, and the endeavour was successful.

He continues: “Now the old films are doing better than some of the new ones, and we started that trend. It's only in a country like India that this happens.” He also screened Mahal (1949) — a black-and-white film — on a day when it was raining cats and dogs. Yet, 1,500 people turned up. “Even for Sholay — did you see the line? What we did was bring back cinema — that’s how a film should be seen,” he says. “It has become a craze now. People are releasing all their old films, and people are watching them on the big screen, even though they are available on streaming sites. That is a big win.”

A Pan-India Phenomenon

This trend isn’t limited to the Hindi film industry. Down south, Siyad Kokker, the producer of the Malayalam film Devadoothan, had to wait 24 years to get closure for a movie that had nearly destroyed his career. “Emotionally and financially, the release of Devadoothan is still, what I consider, the most tragic phase of my life. We believed we had made a classic, but upon its release, the audience did not get the spirit of the film. The ones who liked it were just a handful, whose taste was more progressive than the average moviegoer, but we were warned of its fate before release.” he says.

Kokker feels social media gave him the confidence to release the film again — this time with a remastered version in 4K resolution and Dolby Atmos surround sound. “It’s a film that was advanced in all the technical aspects when we first released it — be it sound, visuals or music. We needed to preserve that by bringing it up to today’s standards. A re-release must be done after a technical upgrade, and that is what makes the difference for people who’ve already seen the film on TV.” This is also the case with Tumbbad, an experiential film, which Shah says “has VFX and an extensive production design. The idea was that if it’s raining on screen, the audience should wonder why it’s not raining outside when they leave the theatre. It’s immersive.”

Kokker spent ₹50 lakhs to remaster the film in a process that took more than eight months. He also took the chance to re-release his film before the trend kicked off. “Today, the movie has collected multiple times what it had upon its original release as a big Mohanlal [actor, producer] starrer. More than the financial success, it gives me, its director [Sibi Malayil] and writer [Raghunath Paleri] the validation that our instincts were not wrong all those years ago. It’s a bittersweet feeling.”

Shah agrees that it’s a pan-India phenomenon because, ultimately, people just want to watch good films on the big screen. “For the average middle-class family, there’s not much to do on a weekend; they can either go out to eat or watch a film. But prices have risen due to OTT platforms coming in, and they (the OTT platforms) aren’t accepting many films. So good movies aren't being made,” he explains.

That’s why old films are returning to the theatres, which, in Shah’s opinion, is a good trend. It recovers costs while bringing in a healthy dose of competition for new releases. However, Madhavan disagrees; he doesn’t think this can become a new business model in the industry. “I don’t think it’s a viable proposition in terms of making great money out of re-releases. For smaller films, you can make a considerable amount of money to cover losses, but I doubt re-releases would recover the entire cost of the film and publicity in today’s world.”

Whether old films are returning due to nostalgia or a dry spell at the box office, it’s certainly giving the actors and filmmakers a second chance at success. In some cases, like that of Tumbadd, it has also opened the door for a sequel. Shah admits he cannot reveal much about Tumbbad 2, except that the story has already been written, and they hope to start shooting next year.

Reflecting on the trend of re-releasing old films, the producer in him has only one thing to say: “It’s a cliché, but if a film is made with good intention, satya pareshan ho sakta hai, parajit nahi — the truth can be derailed, but never defeated.”