Suggested Topics :

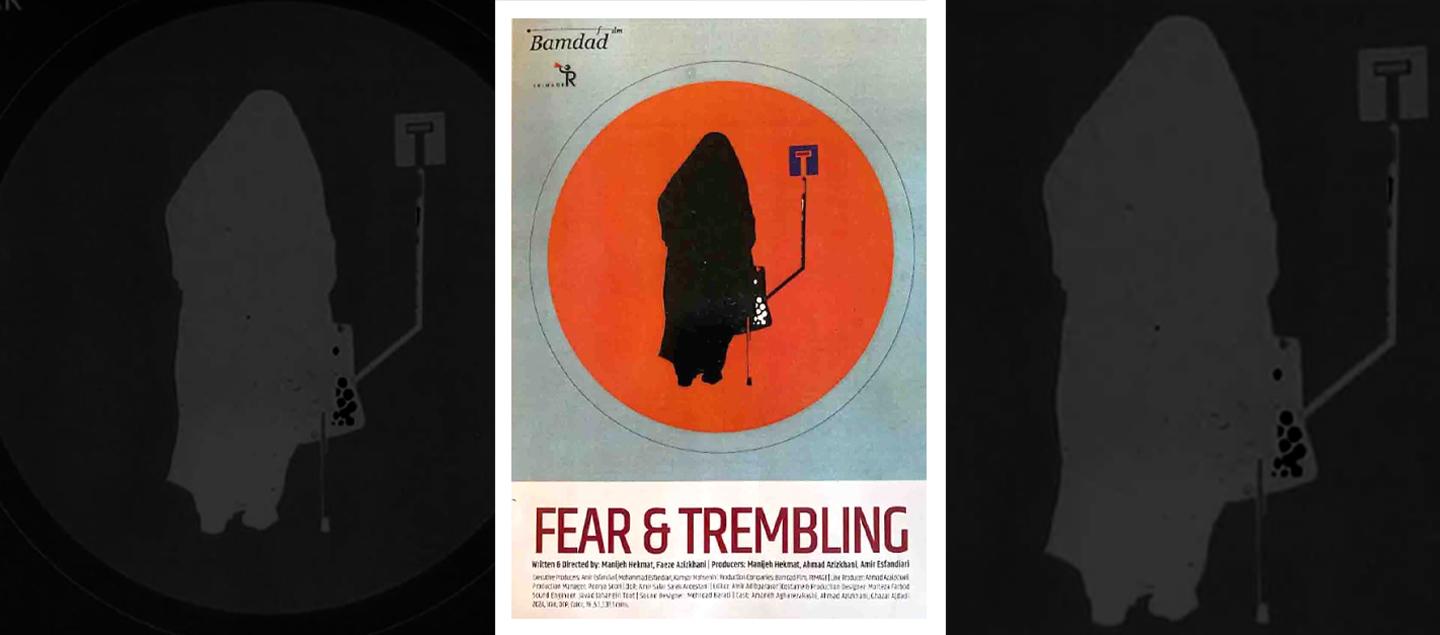

IFFI 2024 Dispatch: Fear, Trembling And One Of The Best Performances Of 2024

Notes on ‘Fear & Trembling,’ a low-key Iranian gem in contention for the festival’s Golden Peacock award.

Writing about films at film festivals can be tricky. You can watch up to six titles a day, but the writing part is always at the back of your mind. Where’s the time? What screenings can be sacrificed for a quick dispatch? Will you remember anything at all? Is it fair to ‘judge’ any of them when memories and immersive experiences keep getting overwritten by the next one? What if the heart is too full or too tired? Every now and then, one movie comes along and reminds you why you’re there. The anxiety of festival coverage makes way for a necessity — the burning desire — to immediately write about this film. You can’t think or do anything until you get it out of your system. In my brief time at the 55th IFFI, that film was a world premiere in competition for the main award. It’s called Fear & Trembling. And inevitably, it comes from Iran.

Directed by Manijeh Hekmat and Faezeh Azizkhani, Fear & Trembling stars Azizkhani’s mother, Amaneh Agharezakashi, as an old woman named Manzar. Most films centered around women’s rights and gender oppression in modern-day Iran revolve around the stories of victims, survivors and heroes. But seldom has the protagonist been both an oppressor and a victim at once. Manzar is an old-school fundamentalist, living alone in a large house in Tehran, practically alienated from a family that has no patience for her regressive values. She has health problems — possibly early-stage Parkinson’s and arthritis — but they pale in comparison to the decayed machinations of her mind. The film opens with her finding out that her niece has been arrested for not wearing a hijab. Her family members — including an adult son, daughter and her estranged sister — call her all day and implore her to provide the document they need for the release. But Manzar stubbornly holds her ground, maintaining that her niece deserves to be punished for sinning in public. She believes that women like that have no place in society, and that their husbands and fathers should have kept them in check.

The film is remarkable on several levels. It entirely features Manzar on her own, pottering around her apartment, outraging and muttering to herself, wallowing in a stuffy sea of self-pity and bitterness. Characters in films usually speak to themselves as a device of exposition for the audience. But Manzar’s habit is far more natural — it’s clear that she is a long-time companion of loneliness, and like most ageing parents and grandparents, she subconsciously uses her voice as an illusion of agency in a space that has moved on from her. If she talks, she assumes that someone is listening. Not once does this ‘dialogue’ sound forced. In fact, her mumbling becomes a reminder of her own culpability in a culture of silence and subservience. Her family members hang up on her when she rants on the phone, and at times, it feels like the camera is her last hope. She is almost aware of its presence, except this is not a nonfiction film.

Agharezakashi’s performance is the finest depiction of accumulated life — of the frayed relationship between fascism and grief — in the context of these divisive times. You can hear her laboured breathing, the creaking of her joints, the sighs disguised as groans, and the fragility of both her body and her beliefs. You can tell that, at this late stage, Manzar is desperately clutching onto her convictions and blaming the world for deserting her because she doesn’t know how else to justify her situation. It’s all futile now, but she has no choice; it’s too late to “change,” even if it means she might not die alone. It’s the kind of performance that allows the viewer to see her as an embattled tragedy of her own making. You feel sorry for Manzar like you would for just another difficult and cranky pensioner. At some point, it stops mattering what she stands for. All that matters are the delusions of a forsaken old woman, divorced from the humanity of a land she no longer recognises. It’s a rare accomplishment, especially in an era where it’s impossible to separate a character from their politics. The film is an empathetic cautionary tale; it doesn’t villainise her because perhaps it doesn’t need to. There’s no patronizing tit-for-tat tone, with the naked reality itself serving as the message. At some level, it evokes the final act of Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019), in which a former gangster in a retirement home struggles to confront the sheer pointlessness of his violent journey. Mortality waits for nobody, but it also democratises the morality of those who wait. Manzar’s worst fears — of insignificance, not death — have been realised, and there’s not much she can do about it.

If anything, the real-time storytelling affords her the dignity of being herself in the face of great opposition. Manzar’s truth is not unlike anyone else’s — the only difference is that this truth has morphed into denial over the years. She has fought to the end, and through another lens, she could be a revolutionary who has simply painted herself into the corner for the sake of her principles. At one point, a long unbroken shot shows her painstakingly writing down her will, hoping to die in her sleep that night. But the next morning brings with it a fresh hell of survival, and the emptiness of dealing with the consequences of who she is.

Watching a film like Fear & Trembling in this day and age is an interesting experience, too. There was no shortage of walkouts at the festival screening. Some of it might have stemmed from the fact that not much “happens” in the film; it’s just one person going about their crumbling existence. Every act is amplified, and every gesture is indistinguishable from the mundanity of being. But I also suspect that much of the reaction came from the more personal space. Most of the walkouts were elderly moviegoers. It can be unsettling to watch a bare reflection of the end for a generation that’s not used to being held accountable for shaping the communities we live in. Imagine being unable to escape into a screen that, slowly but surely, turns into a mirror. Imagine being confronted with a future of fear, trembling and a whole lot of nothingness.