Suggested Topics :

IFFI 2024 Dispatch: Of Shepherds, Locusts And The Language Of Revolution

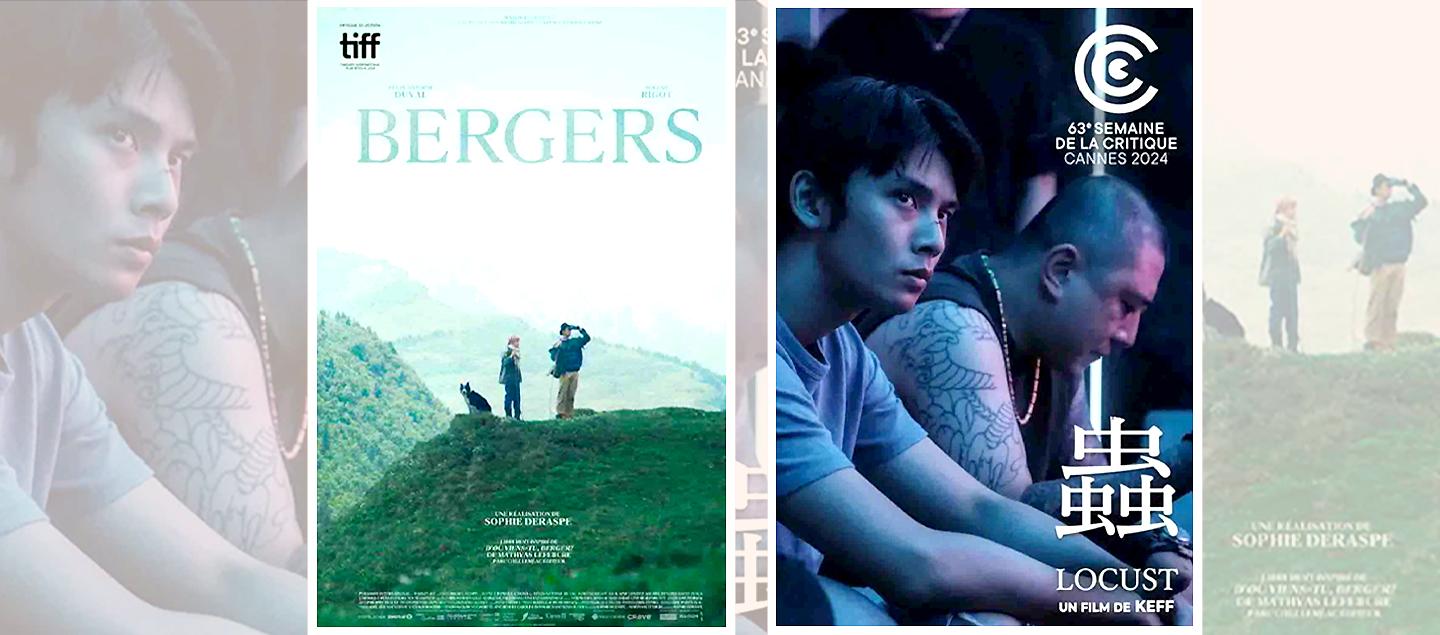

Notes on a French-Canadian writer drama and a Taiwanese tragedy

Sophie Deraspe’s Shepherds opens in the South of France. The first shot is very writerly: cobblestone streets, a town square, remnants of the previous day’s market, a quaint little place waiting to wake up. It’s the kind of escape-it-all view one imagines when they’re stuck in a dead-end job in a bustling city thousands of miles away. As it turns out, this point of view does belong to a writer, Mathyas (Félix-Antoine Duval), who has quit his advertising job in Montreal to “travel and become a novelist”. He’s left his previous world behind in search of words and nomadic experiences. He is young, foolish, idealistic, and he knows it — the kind of aspiring author who perhaps talks and thinks about writing more than he writes. But his credit card is full, and the nothingness often slows down his heart rate so much that he passes out. So Mathyas, just like that, decides to become a shepherd. For him, it’s an existential pause in time. For those who train him, however, it’s time itself. He cannot afford to be a visitor passing by.

Deraspe’s film does a fine job of balancing romanticisation and reality. The apprenticeships are tough on Mathyas, and initially, Shepherds feels like a template-writer tale in which the dreamy-eyed, city-slicking protagonist is humbled by the ‘nature escape’ he chooses. Every time he starts to get comfortable and confident, he gets a rude shock. But the film-making doesn’t thwart the gaze of that first shot. There’s no teach-him-a-lesson vibe. He continues to look at the world aspirationally, and even finds a soulmate along the way. You can tell that the sheer physicality of shepherding is building his emotional and intellectual muscles. But he isn’t doing it to become a novelist or a deeper thinker; he’s doing it because the controlled detachment it offers redefines his own sense of attachment. As an undocumented immigrant, it offers him a chance to belong to people rather than a place. The goodbyes are often abrupt and harsh — the first shepherd refuses to train him after trying him out for a day, the second is a bit of a self-destructive maverick, and the third is almost too good to be true. The film doesn’t bring back any of these characters for the sake of narrative closure. Just like life, it moves on.

Shepherds is a beautifully shot film because it internalises a writer’s perspective, and a lot of it unfolds in the French Alps. But the way it looks is a language of its own. For instance, during one of the ‘tougher’ and more isolated jobs, Mathyas fantasizes about having sex on top of a grassy hill under the sun. Later on, the fantasy comes to life, and it’s exactly as he imagined. That’s not to say his shepherding journey is easy or gorgeous; it just has its moments. His reality is allowed to be a little romantic. Félix-Antoine Duval delivers a perfect body-language performance. His physical transformation from a soft-looking ‘tourist’ to a hardened man of the land sneaks up on the viewer. He manages to grow up, visually even, without entirely losing the naivety that made him so adventurous. He resists turning Mathyas into a new-age farmer whose emotions and sensitivity redefine the profession. It’s the sort of spirited turn that humanises the concept of the ‘world traveler’. He puts a face to the wanderers we come across — those who explore and experience like they have no home to return to.

On the other end of the isolation spectrum, there’s Liu Wei-chen’s simmering performance as Chung-Han, the reluctant protagonist of Locust, the feature film debut of Taiwanese-American film-maker KEFF. Chung-Han is mute but not deaf, a metaphor for the geopolitical setting of the film. It’s 2019, the Hong Kong protests are in full flow: Taiwan and its youth can hear everything but they have no voice. Chung-Han works at an old noodle shop by day — a shop struggling to survive the nowhere-gentrification of a city overrun by greedy builders and politicians. The owner’s lease is almost out, but he remains defiantly antiquated in the face of the changing landscape. Chung-Han is part of a violent loan-collecting gang by night. It’s not long before their blood-thirsty leader weaponises their class rage; they resort to abducting and robbing wealthy club customers because “they deserve it”. The film follows Chung-Han’s slow-burning but inevitable descent into the locust-like swarm of corruption and revenge.

Wei-chen gives the character a distinct 1980s Hong Kong action-hero vibe, allowing the story to find refuge in the permanence of his pauses. Chung-Han is going astray without realising it, because even his voicelessness is falling on the deaf ears of a culture that’s reduced middle-class life to a bunch of sensationalist news cycles. The youngsters look up from their phones and notice the television screen to see the latest culinary sensation, but the riots in Hong Kong elicit little more than shrugs. Chung-Han’s spiral into a headline is full of little beginnings (a girlfriend, warm employers) and false endings. At times, the screen fades to black for long enough to suggest that not even a climax will change the fate of those like Chung-Han. His reality is so damning that he can’t romanticise about getting away from it all as if he were a French-Canadian writer. There is no shepherding of fortunes.

He’s more of a coming-of-rage character than a coming-of-age one — resigned to themes of heroism, antiheroism and sacrifice within the tragedy that’s afforded to him. Ultimately, Locust is not a great film; it almost dares the viewer to be patient with its 134-minute running time, predictable implosions and mood-piece staging. But it’s a story that exudes the identity of its central character and country. It’s like watching the anatomy of a full-scale riot that features one person. It’s a film by default because that’s how the rest of the world — including foreign viewers at film festivals far away — can understand its voice. After all, silence is the universal language of complicity.