Suggested Topics :

The Ultimate Duel between Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen

A war of letters ensued in The Statesman newspaper following Satyajit Ray's scathing review of Mrinal Sen’s Akash Kusum (1965). It ended in Ray parting ways with his closest rival for a lifetime.

Following is an edited excerpt from ‘At Home With Mrinal Sen’ by Dipankar Mukhopadhyay (Om Books International, ₹395), an up-close and personal account of the rebel filmmaker who pioneered the Indian New Wave Cinema, from the perspective of his close friend and confidante. While Mrinal Sen and Satyajit Ray helped each other through their careers — Sen suggesting actors to Ray, Ray pushing Sen’s ‘Baishey Shravana’ (1960) into the gaze of international critics — in 1965, this friendship was put to test by a series of letters in the local newspaper.

***

It all began with a series of letters that were printed in The Statesman, Calcutta’s most prestigious English daily at the time.

In 1965, Mrinal Sen made Akash Kusum. It is the story of a young man of a lower middle-class background who falls in love with a woman from an affluent family. Fearing rejection, he presents himself to her as an upcoming but successful businessman. She believes him, which means he has to continue the charade. He begins to borrow heavily from a rich friend and tries some shady, quick-fix methods to become rich overnight. In the end, he fails miserably and loses whatever he has, including the girl.

Based on a story written by Ashish Barman — a distant relative of Satyajit Ray — Akash Kusum became a powerful exposé of urban consumerism, thanks to Mrinal Sen’s film-making. Sen used a light-hearted style to lead the unsuspecting audience to a grim climax. As a social commentary, it hit hard, which is probably why Akash Kusum failed, both in terms of commercial and critical responses.

Contemporaries such as Santi P. Choudhury, a well-known documentary film-maker, hailed Akash Kusum as the first truly urban Bengali movie. Professor Amalendu Bose, head of the department of English in the University of Calcutta, lamented that the average moviegoer was so engrossed by the hero’s antics that he failed to appreciate the tragedy of the story. However, there were many others who disagreed with such opinions.

In his review of Akash Kusum, which appeared in The Statesman on 23 July 1965, the paper’s film critic had observed that ‘had the film ended on the same seriocomic mode, probably the audience would have been more sympathetic to the hero’, going on to say, ‘The revelation of the deception that the hero had been practicing was fit occasion for some high comedy, at the end of which the hero might still have retained, like Don Quixote, his schizophrenic view of the world but we could have got our laughs while in some street-corner of our heart we would have retained as we do for the knight of the woeful countenance — a trace of sympathy, even admiration for this hopeless dreamer.’

Barman reacted sharply to this critique. He wrote back: ‘We feel a Don Quixote ending for a contemporary story with all its immediacy of the scene would have been totally unconvincing and hence dangerous. For a period piece, no doubt, this could have been a plausible postulate. This cinema mirrors the reality too objectively, with a ruthless precision and lucidity of the images; hence it is almost impossible to lend stylised ambiguity of a topical theme. I stress the word ‘topical’.

The editor of The Statesman thought the matter was over after this sharp exchange of words between his film critic and Ashish Barman, but then came a response from someone who could not be silenced. Satyajit Ray sent his comments and in his inimitable style, he delivered a scathing dismissal of Akash Kusum.

Ray wrote: ‘May I point out that the topicality of the theme in question stretches back into antiquity, when it found expression in that touching fable about the poor deluded crow with a fatal weakness for status symbols. Had Mr Barman known of the fate of this crow he would surely have imparted the knowledge of his protagonist, who now acts in complete ignorance of traditional precepts, with — need I add — fabulous consequences. … It is almost impossible to lend stylised ambiguity to a topical theme. I stress the word ‘topical’.

An enraged Barman responded immediately: ‘I am flattered to see that Mr Satyajit Ray, one of the greatest film-makers of the world, has taken note of my letter pertaining to your film critic’s review of our film Akash Kusum. In his nimble comments however, he has mixed up two different aspects of a topical theme; for the topicality of the story does not negate the basic human urges like love, jealousy, hunger, hope or the desire for a better life. What it does is to stamp these basic urges with the contemporary forms and the urgency of a central focus. As far as the question of imparting the precepts of antiquity is concerned, may I remind Mr Ray that great men like Christ, Buddha, and Gandhiji have done the same from the past — evidently with not much success.’

At this point, Mrinal Sen entered the fray. While talking about the duel of words years later, Mrinal-da insisted that he began writing not to continue but to close this exchange. He wrote to The Statesman: ‘I am rather tempted to bring in a champion in this seemingly exciting polemics — Chaplin — who, made much in the image of the poor deluded crow of Aesop’s fables, expressed, to quote his own words, ‘my conception of the average men, any man, of myself ’. His derby, according to him, strove for dignity, his moustache for vanity and so on. And in later years after World War II, when the world was atrociously different — old fatal weakness for status symbols drove Chaplin to kill a dozen women. And I am sure Mr Ray will certainly not doubt the topicality of Chaplin’s theme brought out with such mastery during the long years of his film career. Was it not this madness, which is so palpable in all Chaplin’s works, evident in Don Quixote which yet remained contemporaneous, and in our days do we not share the same aberrations in lesser or greater degree with indeed ‘fabulous consequences’? I do not, by any chance, wish to take refuge under the fabled crow’s wings and claim to be an Aesop or a Cervantes or Chaplin. I have made a film called Akash Kusum and that is all.’

Sen’s comments did nothing to douse the debate. Missives from Ray, Sen and Barman continued to appear, each one fanning the flames of controversy. Sen sent rejoinders, Ray reacted with unpleasant comments. Sen and Barman insisted Akash Kusum was a portrait of contemporary society that reflected the restlessness of the youth, while Ray saw the film as a plain, simple and badly made comedy.

The ‘Letters to the Editor’ column in The Statesman started filling up with comments from all quarters. Film buffs and cine-club members such as Barun Chanda commented, ‘Mr Satyajit Ray has overlooked the possibility that there are people who can overgrow children’s fables, or, better still, translate them into an adult language.’ Rajat Roy Choudhury added, ‘Mr Satyajit Ray instead of constructively criticising the film Akash Kusum, in a roundabout manner pulls its director and story-writer’s legs and quibbles with words. Mr Ray himself borrows from old and outdated stories and ideas in his films. How then he can blame anyone for such borrowing?’

As the controversy snowballed, regular readers joined in. One film enthusiast wrote, ‘Mr Satyajit Ray’s Big Brother attitude towards Mr Mrinal Sen and Ashish Barman is surprising. Akash Kusum has contemporaneity in its very theme and not on the surface. Castle building in the air is topical enough.’ Another film enthusiast wrote, ‘The exchange of letters between Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen and Ashish Barman is amusing. In his latest letter (August 21-22) Mr Ray considers himself to be an authority on what he calls “contemporaneity”. I doubt it very much after seeing Kapurush.’

The very next day a letter was published supporting Ray. Dilip Ghosh wrote, ‘Mr Satyajit Ray has rightly classified Akash Kusum as a crow-film. Any enlightened viewer will find a very great difference between Chaplin’s tramp and Mr Barman’s hero whose entire thinking rolls around bluffing.’

This exchange of letters rekindled the audience’s interest in seeing the film. One viewer wrote after watching it, ‘I have read with interest the letters on Akash Kusum and now I have seen the picture and feel constrained to say that it has not been able to retain the reputation of Mr Sen as a film director. It is a commonplace production. Except for some lively dialogue, there is hardly anything praiseworthy.’

On 1 September, The Statesman carried a comment on the film by Ray in which the film-maker deliberately used the word ‘contemporary’ in every sentence and ended the letter with a statement that remains famous for its savagery:

‘A crow-film is a crow-film is a crow-film.’

Sen wrote back quickly: ‘In trying to derive a ‘contemporary moral’, Mr Ray by adding three doubtful prefixes, has conveniently reconstructed a famous line which originally belonged to the French film director Jean-Luc Godard: ‘A film is a film is a film.’ In this connection it may be interesting to note that Mr Godard, unlike Mr Ray, prefers to remain amoral and will perhaps ‘suffer’ many human frailties, including ‘persistent lying’ even ‘in beds’.’

An anguished reader was so provoked by these exchanges that he wrote, ‘Only one person does not know how great Mr Satyajit Ray is. That is Mr Ray himself. How else could he stoop to attack a poor colleague so mercilessly?’

Another wrote back, ‘As a result of this controversy, all that has happened is, a mediocre film has received tremendous publicity and the general public has lost some of its regards [sic] for Mr Ray.’

On 13 September, the management of the newspaper officially brought the matter to a close by declaring no more correspondence on the subject would be published ‘as it is nobody’s loss, nobody’s gain’.

By coincidence, the two film-makers met at a Film Society meeting on the same evening. Ray said to Sen with a smile, ‘What a pity it ended too soon. I could have written many more letters.’ Sen replied, ‘I have neither your firepower, nor your support base. Yet I would have replied to each of them.’

…

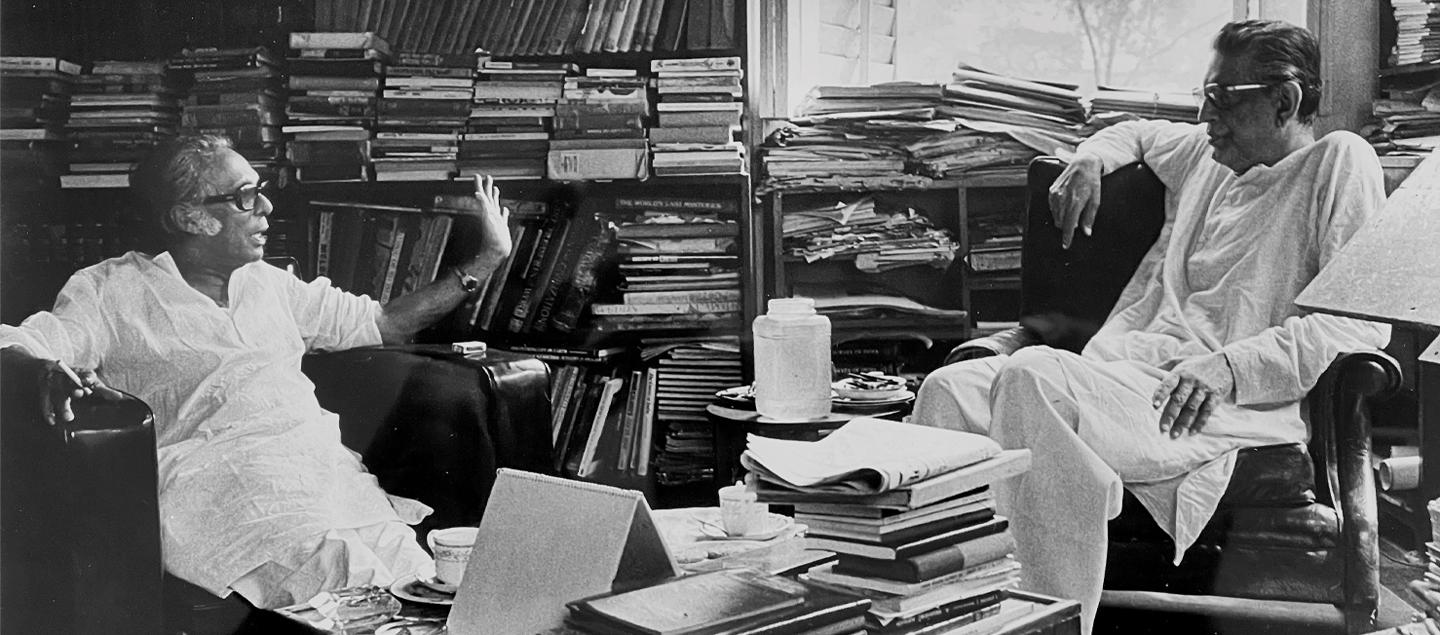

Almost thirty-five years later, one afternoon Mrinalda and I were alone in his house and we found an old copy of The Statesman. I asked Mrinal-da about the rift between him and Ray. He smiled and said, ‘One evening, Manik babu rang me and said, “I won’t hurt you, I just want to make some observations on Ashish’s story.”

Naturally, I had no objections. Then in his inimitable style, he wrote something about the story, which was a bit critical. Ashish immediately hit back, which he could have avoided. I need not have reacted but I also joined the fray, initially just for fun. Again Satyajit Ray wrote a letter. Again Ashish replied and I sent in my rejoinder. The whole issue snowballed, more than a hundred people joined the debate and it became a raging battle between antiquity and contemporaneity.’

To my mind, Ray recognised that in Sen he had a rival, and as appreciative as he was of Sen’s film-making talent, as a cinephile, it also unsettled him. While Ray belonged to one of Calcutta’s most elite families and had enjoyed the benefits of this, Sen was from the backwaters of Faridpur with no social capital to speak of. Ray was an alumnus of Presidency College and Santiniketan; Sen had been a student of science from an ordinary college. Before entering the world of cinema, Ray was already known to be a talented illustrator and had a senior position in an advertising firm. Sen worked as a medical representative. Ray and his friends had formed the Calcutta Film Society. Sen, in contrast, could not afford the membership fee. Ray was a success story with his very first film. Sen had a string of failures till Bhuvan Shome.

Despite the lukewarm response it got, I think something about Akash Kusum made Ray realise that Sen had succeeded in telling the kind of fable Ray had tried to in Paras Pathar, but without much success.

Paras Pathar came out in 1958 and was about a lowly clerk who chances upon a magical stone and becomes rich. Ray attempted to use it to create a contemporary portrait of Calcutta, but both critics and audiences treated Paras Pathar as a simple, light-hearted comedy, a children’s film. In contrast, Sen had taken the simple story of Akash Kusum and used it to explore the same desire to become rich and was able to link it with issues plaguing the everyday lives of middle-class Calcutta.

Perhaps this is why Ray had insisted Akash Kusum should be seen as nothing more than a mere comedy — much like Paras Pathar had been — and criticised Sen for changing the tone at the end by introducing seriousness to the tale.