Suggested Topics :

THR India's 25 in 25: 'The Great Indian Kitchen' is a Revolution at the Sink

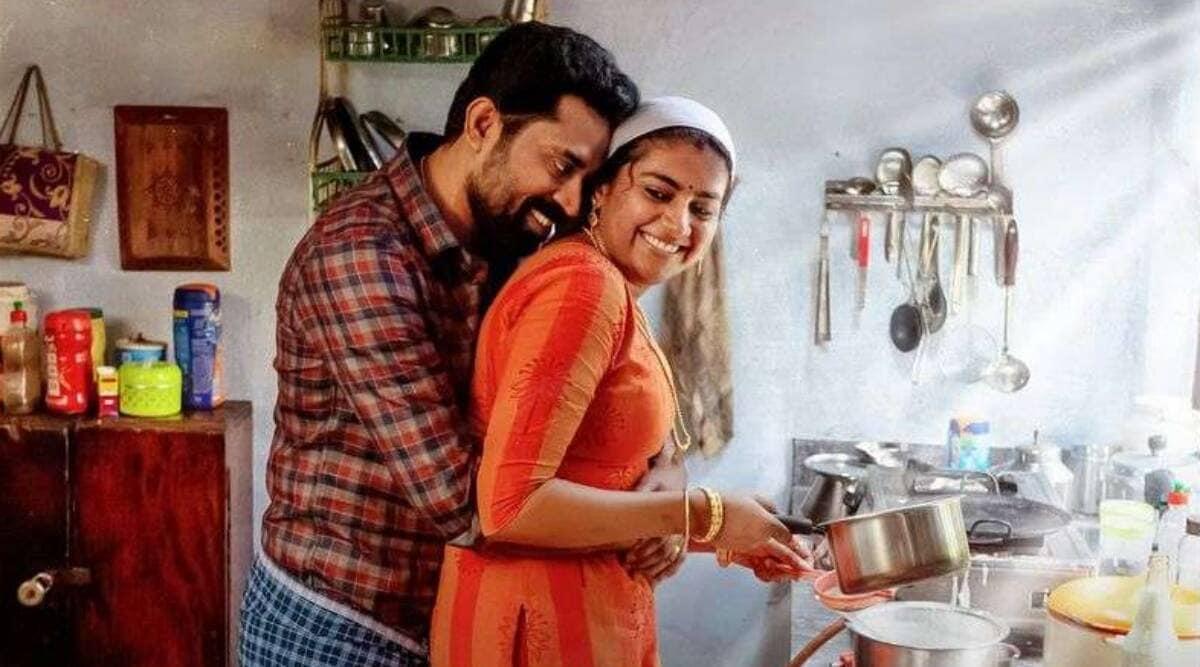

The Hollywood Reporter India picks the 25 best Indian films of the 21st century. Jeo Baby’s scathing domestic drama 'The Great Indian Kitchen' turns ordinary chores into an indictment of patriarchy itself.

In Jeo Baby’s The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), a disgusting and messy dining table becomes a damning symbol of patriarchy. A space abandoned by men too entitled to eat with dignity and left to be wiped clean by the women who are expected to sit at the same table, as second-class citizens in their own homes, permitted neither rest nor respect. This is the normalised cruelty that powers Baby’s searing critique, suffocating audience members with the slow grind of domestic labour rendered with such precision that the repetition itself becomes unbearable. The housewife at the story’s centre (Nimisha Sajayan) enters her new marriage dancing, literally, flushed with joy, only to be reduced to her mother-in-law’s shadow and, when that mother-in-law departs, to a prisoner in her own kitchen.

As the demands pile up, she is allowed to occupy less and less space in her own home. Even sex becomes akin to duty. In a devastating scene, her husband moves on top of her while she lies there inert, sniffing her fingers, unable to rid them of the smell of onions and oil.

Baby, drawing from his own disillusionment at home, insists on the details: the endless chopping, frying, scrubbing, the casual indifference of men who neither notice nor care. He refuses melodrama — the husband, played with chilling banality by Suraj Venjaramoodu, never raises his voice, only asserts his entitlement with every gesture.

With no background score, only the sounds of drudgery, Baby and cinematographer Salu K. Thomas compose frames like miniature stills of waste and frustration, until the explosion arrives, righteous and cathartic. The Great Indian Kitchen is not just a film but a reckoning, revealing how oppression thrives in the most ordinary spaces, and why the Indian kitchen may be the country’s most contested battlefield.

Jeo Baby on Making The Great Indian Kitchen

Baby never imagined his small, self-financed film would spark a cultural firestorm. The Great Indian Kitchen was born of the director’s own exhaustion in the kitchen after marriage and was conceived as “a kind of self-expression…something personal.” Initially rejected by every major platform — “the exciting fact is the movie was rejected by men in decision-making places,” he says — it found its first home on a modest local streamer called Neestream before word-of-mouth pushed it into the mainstream.

“We went to every major streaming platform, and we realised that they did not want our film because all of these men thought there was no audience for this story,” he says. What carried it there was not industry validation but audience conviction, especially from women who saw their own lives reflected in its fury.

“Suddenly when it went viral all these same platforms came back to us wanting to acquire our film,” he says with a laugh.

Baby chose not to script dialogue in advance, instead “fine-tuning every line with the actors on the day,” allowing the oppressive routines to feel unbearably real. The monotony itself becomes the film’s language. “I take this experience with me everywhere I go. I let the nuances emerge organically,” he says.

The responses the director got from members of the audience were (and continue to be) overwhelming. “I got more than 100 messages from men saying they started washing their own plates, helping in the kitchen,” he says. Women flooded his inbox too: This is my life; this is my story. “I have been reading every single message, and it really makes me very emotional when I hear the stories and how it changed people’s lives. I still think it’ll take 10 to 12 more months for me to read every message in my inbox,” he says.

Its legacy lies in that collective awakening. With stark images and unflinching patience, The Great Indian Kitchen transformed the most private of spaces into a battleground of gender, labour, and power. “I don’t think about things like legacy. It was a moment of self-expression for me,” Baby says. “By making this film I found a way to honour my partner, too. It changed our lives, and from the stories I’ve heard from audiences it feels like it has somehow managed to leave a mark.”.