Suggested Topics :

Exclusive | Farida Jalal: 'No Actor Has Come Back The Way I Did'

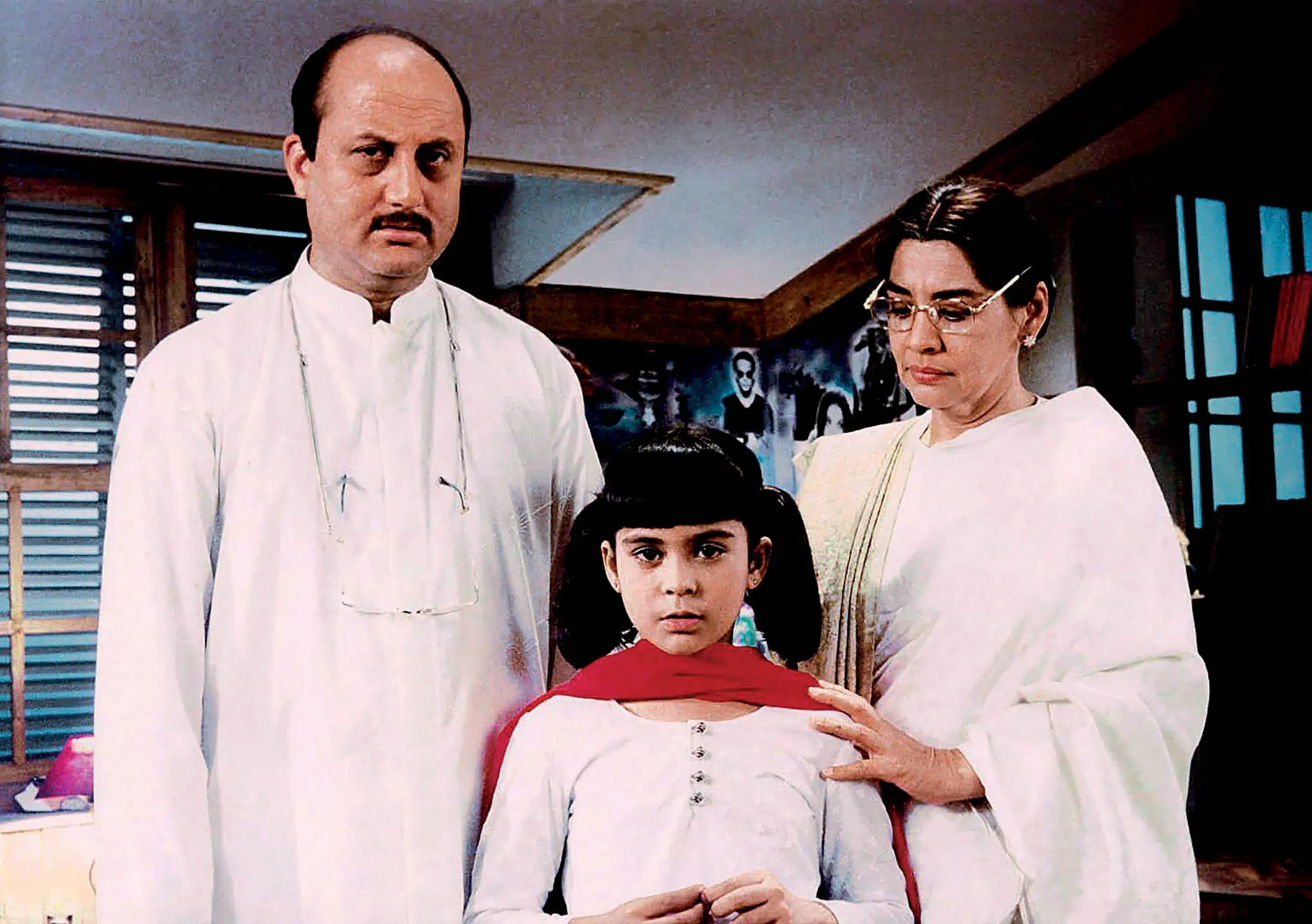

Farida Jalal looks back on a life in cinema shaped by friendship, restraint and a refusal to compromise.

She lives in a sprawling but simple flat in Mumbai’s Andheri, populated with old pictures and VCR tapes but nothing extravagant — a home that reflects a life that was fully lived rather than carefully curated. When Farida Jalal opens the door, the first thing you notice is her gait. Age makes itself known without apology. And then you notice her eyes, bright and sparkling, taking everything in.

“Hello,” she says, and the word does several things at once. She apologises once, lightly, for nothing in particular, then settles into the sofa with the ease of someone who has learned not to perform comfort. “Ask,” she says, and then, as if correcting herself, “No, tell me first. Tell me what you want to know.”

Throughout the conversation, Jalal uses “hello” the way some people use punctuation. It can signal surprise, mild disapproval, amusement, or simply remind you that you are speaking to someone who has seen this world, and this industry, from the inside for over six decades. She is not wearing any make-up. She pauses, looks around, wonders aloud if she should. When she needs to pose for a few pictures, she straightens instinctively, like someone whose body remembers this work even when the mirror is no longer part of the daily ritual.

SISTER ACT

Born in Mumbai when the city still felt like a collection of neighbourhoods rather than an ambition, her mother was determined that her daughter would have discipline, so she went to a convent school, where the nuns taught her posture and punctuality and how to finish what she began. “I was very close to the life of a nun,” she says. “Very disciplined. Very god-fearing. That never left me.” She talks about St Joseph’s, Panchgani, as if it were a second home rather than a school, a place that gave her not just education but a way of being. Years later, when she returned to Panchgani while shooting Bees Saal Pehle (1972), she found herself touching the walls. “Everything I am comes from there,” she says. “Values, grounding, honesty.”

At the same time, she was already obsessed with Hindi films. During holidays, she would watch anything that was playing. “I used to write letters home asking my mother to book tickets. Any film. I had to see one the very next day.” Dancing, she remembers, was discouraged in her school. “The sisters would say, ‘Indian dancing? You’ll be expelled!’ I said, ‘Sorry sister, but I love to dance.’” Eventually, she was performing at every school function, year after year. She laughs while saying this, the laughter bubbling up mid-sentence, never interrupting the thought, only embellishing it.

“That was always my scene,” she says now, almost casually. The phrase comes back often over the course of our conversation. That’s not my scene. That is my scene. It works as a personal philosophy; a boundary she has never felt the need to justify.

She entered films in the late 1960s, winning the Filmfare Talent Hunt and making her debut at a time when actresses were expected to fit a narrow mould. “They said I was short. Not tall, not slim,” she recalls. “I didn’t care. I never did surgeries. I only cared about the scene.” Supporting roles, especially sisters and later mothers, appealed to her more than leading parts. “Those women had interiors,” she says. “They had lives.”

THE WAITING GAME

She was never in a hurry to become a star. “I thank god I was not a leading lady,” she says. “That panic they live with, I never had it.” Her metric for success was simple. “Did I give my 100 per cent to the scene? If yes, I slept well.”

The industry’s current obsession with instant validation leaves her bemused. “Now success is trailer views, teaser shares. I once heard of a success party before release. Hello?” The word lands softly but firmly. Celebrity-first ambition troubles her. “If fame is your goal, it won’t last. It’s very fickle. Always was.”

When she talks about love, she casually talks about how all the leading men used to flirt with her. Her future husband, Tabrez Barmavar, did not behave like that. He watched her, noticed her, waited. She found him irritating at first. “I didn’t like that he wasn’t impressed,” she says, laughing again, this time with recognition. He brought flowers for her mother before he brought them for her. He asked questions and listened to the answers. When he proposed, she said no. Not dramatically, not as a test. She simply said she wasn’t ready. He waited. When she said yes, it was not because something had changed about him. It was because she had caught up with what she already knew.

Marriage briefly interrupted her work. But when her favourite filmmakers followed her to Bengaluru with offers, she realised that she had to go back.

VANITY, FAIR

She learned the difference between attention and intimacy, between being seen and being known. She became more careful about what she agreed to do. She was never interested in being everywhere. “I don’t like noise,” she says. “I don’t like crowds that are pretending to be affectionate.”

She talks about celebrity culture now with mild bafflement, not anger. The entourages, the caravans, the way sets have become louder without becoming more efficient. She remembers a conversation with Raveena Tandon, both of them shaking their heads at the expectation that producers should foot the bill for vanity vans and assistants and comforts that have nothing to do with the work. “We used to come in our own cars,” she says. “We brought our own food if we had to. The producer was not our parent.”

She is careful not to sound superior. She does not accuse. She simply states her preference. “That’s not my scene,” she says. It is not her scene to shout for attention. It is not her scene to confuse busyness with purpose. It is not her scene to stay where she is not needed. This clarity has cost her work at times. She knows this. She does not regret it. “I have never been hungry for work,” she says, and then, anticipating misunderstanding, adds, “I have been hungry for good work.”

Raj Kapoor occupies a singular place in her memories. “The best director in the world,” she says simply. After finishing Bobby, she went to say goodbye. “He said, ‘There is no bye between you and me.’” He attended her wedding, brought gifts, stayed present. Rishi Kapoor remains close to her heart. “I still love him. I still miss him,” she says, her eyes welling easily when she talks about people who mattered.

THE COMEBACK

Henna (1991) marked her return to films after years away. “My comeback was better than my first innings,” she says. “No actor has come back the way I did.” Television followed. Films followed. Work flowed. Television changed the rhythm of her life in ways she did not expect. Sharaarat (2003) arrived as an extension of her career, it gave her more space to breathe.

Comedy, she says, taught her more about listening than drama ever did. Timing was not about speed. It was about restraint. The joke lived in the pause, in the refusal to push.

She talks about ambient viewing now, the way screens have become background noise, the way stories are consumed while doing other things. She does not condemn it. She simply wonders what gets lost. “Acting needs attention,” she says. “Even bad acting needs attention. Otherwise, why are we doing it?” She worries less about the future of cinema than about the future of care. Care in preparation. Care in writing. Care in watching. She has little patience for violence that mistakes shock for depth. She turns away from work that does not trust silence.

Jalal also has little patience for social media culture or camera phones. “Who put a camera in the phone?” she asks, half-laughing, half-serious. “Please find him. I want to meet him.” The irritation is real. Hospitals, airports, private moments. “There is no decorum,” she says. “It’s an invasion of privacy.”

Now she’s almost amused by how much these phones have changed our lives. How they’ve killed the “silence” that we need for good art to exist. Micro-dramas, algorithm-chasing content, second-screen storytelling do not interest her. “That’s not my scene,” she says, simply. Nor does the industry’s current fixation with violence and alpha masculinity. “Where is the tenderness?” she asks. “The biggest stars of our time were romantic heroes.” She has not watched much recently, though she speaks warmly of Homebound. “After many years, I cried,” she says.

FRIENDS LIKE FAMILY

After six decades, the memories come to her as people. She speaks of her favourite associations with an ease that suggests they were never strategic to begin with. Kajol, she says, is one of a kind. If she doesn’t like you, she doesn’t like you, she says, and laughs, as if this is the highest form of honesty. But nobody hugs you harder. “She nearly kills me,” Jalal says, pleased by the excess. Shah Rukh Khan, she calls a perfect gentleman. While shooting for Duplicate in Mauritius, she remembers him wordlessly taking a trolley from her and her mother at the airport. “That’s who he is,” she says. “He can kill you with kindness.”

Her affection stretches easily to the next generation. Watching Aryan Khan’s work, she says, her heart was in her mouth. “I always pray for them,” she says instinctively, as if prayer is simply another way of paying attention. Jaya Bachchan remains central to her emotional life, a constant rather than a memory. “We were thick pals,” she says. When my mother died, she came. When my husband died, she was there. She stops, lets the thought settle. “That’s a friend. That will always remain in my heart.”

It is only then that a note of loss creeps in. She wonders what happened to those friendships, how the industry once full of familiar faces has thinned into occasional messages, long silences. She hasn’t seen many of her old friends in years. The heartbreak, when it appears, is unperformed, a slight softening of the voice. She worries about the younger generation.

“They don’t know what matters,” she says. “They don’t know what’s real.” She isn’t trying to sound like a broken record. It’s just that things have become increasingly transactional, and artists, she insists, are not built for that. “We are soft people,” she says. “We were never meant to be business people.”

Despite everything, her loyalty to the industry remains intact. “If any film does well, I feel happy,” she says. “The industry should thrive.” What gives her freedom, perhaps, is the absence of artifice. No PR teams. No social media scripts. “What’s there to hide?” she says. “Nonsense.” She has never softened herself to be palatable. “Smile more, nod more, be agreeable — I never did that,” she says. “I’ve said what I wanted to say.”

As we finish, she checks in gently. “Anything you want clarified?” she asks. “I was clear, right?”

Clear about who she is, what she stands for, and what she refuses to compromise. Was any of this off-the-record? “That’s not my scene,” Farida Jalal says once more, smiling. After all these years, it still isn’t. And that, more than anything else, may be the point.

To read more exclusive stories from The Hollywood Reporter India's February 2026 print issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest book store or newspaper stand.

To buy the digital issue of the magazine, please click here.