Suggested Topics :

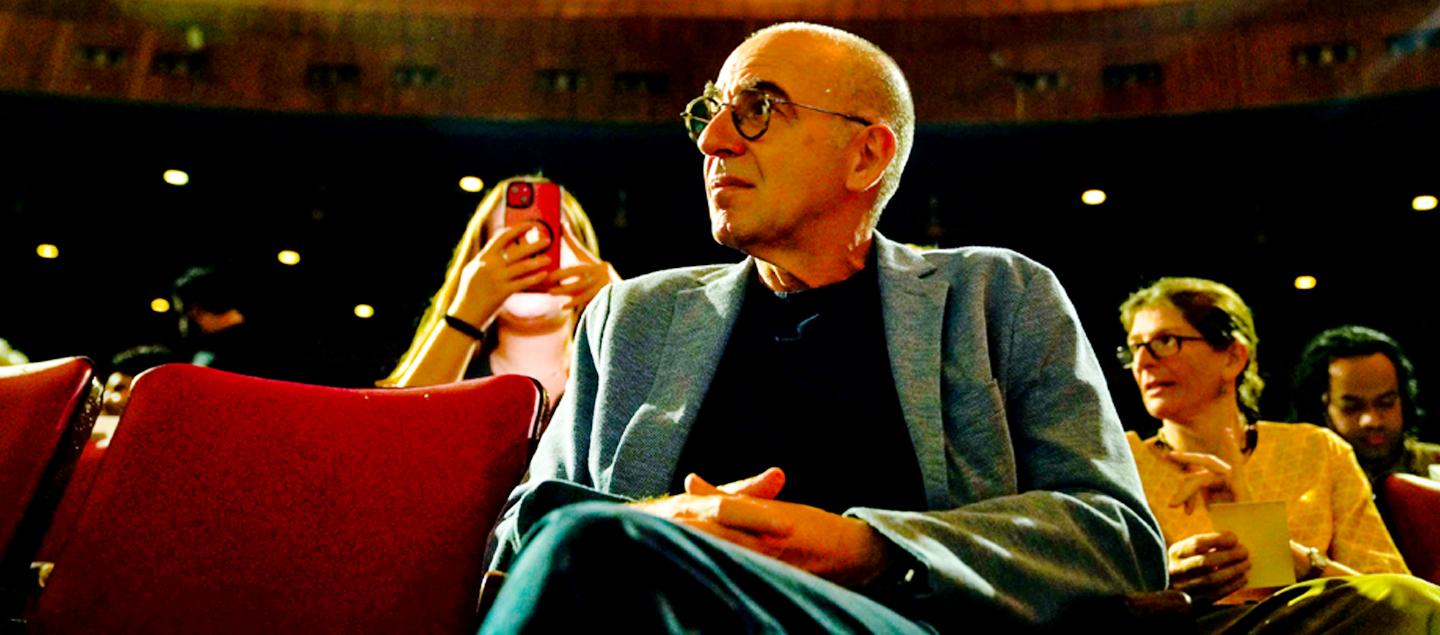

Italian Filmmaker Giuseppe Tornatore Talks About How to Love Cinema

Tornatore, who began his journey in cinema as a projectionist, talks about how he taught himself to be a filmmaker and what he misses about the way movies were made in the past.

Istituto Italiano di Cultura di Mumbai (IIC Mumbai) — which aims to promote Italian culture and heritage by fostering cultural exchange with the local community in India — in collaboration with the Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) — which has been working for a decade to restore Indian films — brought a slice of Italy to Regal Cinema in Mumbai’s Colaba, with Cinema Italian Style. The festival, which ran from September 27 to 29, showcased restored prints of Italian classics, and was headlined by Oscar-winning Italian filmmaker Giuseppe Tornatore. The FHF, spearheaded by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur — who founded the organisation —has played a crucial role in promoting the importance of cinematic preservation. The collaboration with IIC Mumbai, under the leadership of Francesca Amendola, the institute’s director, proved especially rewarding to cinemagoers.

Tornatore, who began his journey in cinema as a projectionist, honoured two stalwarts of projection — Sukumar Ghosh and Chand Kumar Mondal — with lifetime achievement awards. It was a fitting prelude to the festival’s opening screening: Cinema Paradiso (1988).

The Hollywood Reporter India sat down with Tornatore to discuss what makes cinema truly special to him and how he hopes to be remembered.

The conversation has been edited for clarity.

What is your earliest memory of being in a cinema hall, and how has that experience remained special for you even today?

When I was six years old, in my village, we had seven movie theatres, and eight in the summer because we had one open movie theatre. I had the opportunity to go every day to a different movie theatre to see a new movie. We would see the same movie two or three times in the cinema hall, because it was not the way it is today that after the show, you have to leave the theatre and go outside. It was a special time. When I became a projectionist, I was 14 years old. I remember, we got Modern Times (1936) by Charlie Chaplin. I had never seen that movie. Obviously, as a projectionist, you get to watch the show, but I must have watched that film 20 times in a week. I projected the movie for four days, five shows every day. I watched all the shows. It was great.

In what ways did your early experiences as a projectionist, photographer, and documentary filmmaker influence your filmmaking?

I believe that the beginning of my love for images happened through the job of a photographer. That experience totally influenced the way I saw real life — the world around me. I remember when I was shooting my first documentary, I was 14 or 15 years old. I remember I used to study filmmaking through the films I showed from the projection box.

The movie was divided into two parts; we used to project the first hour, then there was an intermission, and then the second part. When I was projecting the second part, I used to have the first part in my hand, and I would study it. By watching hundreds and hundreds of movies, I learned the logic of this language.

As a photographer, I used to have my camera with me at all times. I was constantly taking pictures. For many years, I would follow people and animals to take a picture at the right moment. I would spend the whole day people-watching. Sometimes, I had the opportunity to get some very interesting action. Many times, nothing at all. But I learned to observe people. The way they move, the way they laugh. It was an extraordinary school.

When I am on the set shooting one of my movies, I can immediately tell if one of my actors is not being realistic. It’s impossible to write it down in the screenplay — you have to walk realistically. It has to feel correct.

Your cinema is rooted in realism, and you also grew up during the Neorealism movement in Italy. Have you never felt the need to explore other styles, like fantasy?

I love the realism in movies. The experience of Italian neorealism was so strong, not only for Italy but for the whole world. It was probably the best experience in the history of movies. I like the idea of my films being realistic, but it’s not like I don’t like other styles. I like all the styles. I was educated to love every kind of movie. I love fantasy, horror, thriller, fantasy, sci-fi — everything.

How do you love everything?

There are two reasons for this democratic love. One, in the movie theatres that I used to go to, or in which I was the projectionist, we did not have genre-specific theatres. A classic film could be followed by a modern one. On Sunday, a blockbuster would be shown. On Monday, a film by Ingmar Bergman would be shown. The day after, a musical. So, I watched everything without discrimination.

But, more importantly, my teacher of projection arts taught me something very important. He said, “Remember, when you project a movie, it has to be perfect every time — the light, the focus, the sound. You must always do your best. Even if you are projecting a movie that you don’t love — every movie must get the same treatment, the same rights.” The democracy of technology made me open up to all kinds of movies and love every kind of movie.

When I go to a movie theatre, I love to be a spectator. I need only one or two sequences that will make me love the movie. Even if the movie is not great, I'm a generous spectator. Inside the movie theatre, I love the movie simply because it exists, and I know how difficult it is to make a movie.

Your love for cinema can be felt in Cinema Paradiso (1988). Do you think that the romance of cinema has lessened in the digital age? Especially with people watching movies on their phones?

Obviously, many things have changed with the digital age. Forty or fifty years ago, the crowd in a movie theatre was electric. People used to speak to the characters on screen; they used to have a relationship with the actors, the actresses. They even spoke to each other during the film and many days later at the town square. Today, the atmosphere is very cold.

Obviously, I'm not very happy that people watch movies on their phones. It is impossible to understand the wide shot on the phone. They can understand only the close-up. Many movies today are only made of close-up shots because the way you watch the movie influences how it is made and, in turn, influences the language.

I don't love this, but I prefer that people watch the movie on their phone if the alternative is not watching it at all. Maybe watch it on the phone and love it enough to come to see it on the big screen. The magic is in the movie theatre.

The relationship between the big screen and your memory is strong. When you watch the movie on your phone, you don’t even remember it. When you watch it in the theatre, the images stay in your mind.

Is there something about making a movie that you don't like?

There is probably only one aspect that I don't love so much. It is the time that you spend looking for a producer, a co-producer, a distributor. That's tiring. Forty years ago, you only had to speak to one person — the producer. I would narrate my story to one person. If that person liked my story, he decided to do the movie.

Today, I have to narrate my story to a producer, to his partner, to the partner’s friend, to a co-producer, to another co-producer in another country, to the functionary of the platform, to a lawyer, to the agent of the actor! You have to narrate your story to hundreds and hundreds of people, trying to convince them that your story has the right to exist.

It's so tiring.

How do you want to be remembered?

I would like people to remember me for the movie that I am yet to make.