Suggested Topics :

‘Babli by Night’: A Transperson’s Tale of Belonging, Solitude and Resistance

Neel Soni’s BAFTA-longlisted short, 'Babli by Night,' is an intimate portrait of trans identity and wilderness-bound freedom.

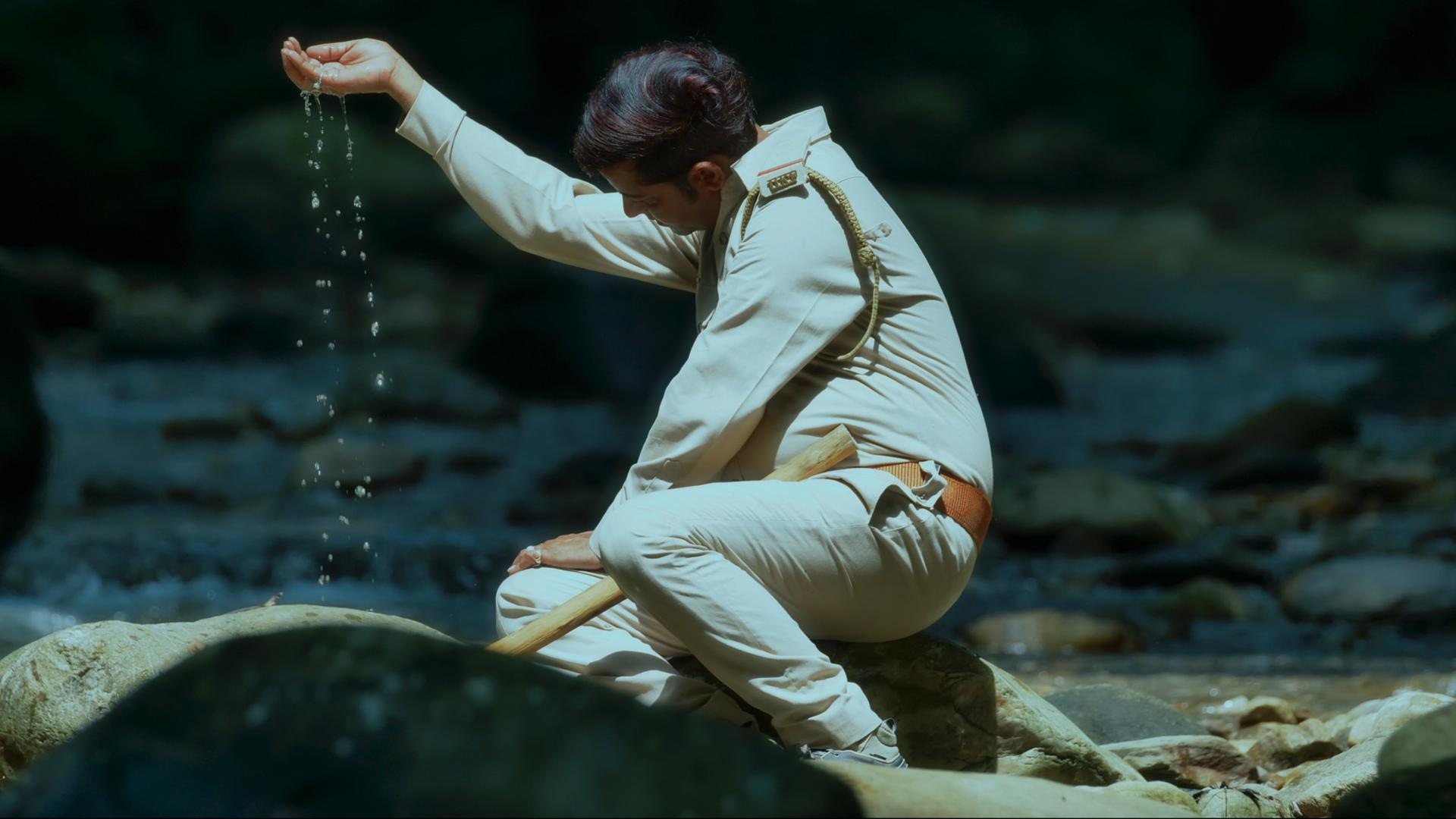

When 23-year-old filmmaker Neel Soni’s camera faces Babban, a forest guard in Uttarakhand’s Jim Corbett National Park, it almost immediately refocuses its lens to reveal Babli in all their tenderness, moving through the world with a spring in their step, dreaming of building a home with their man.

Soni, a Delhi-based filmmaker who recently graduated from New York’s Pratt Institute in cinematography and video production, met Babban a decade ago when he was 13, while on a trip to the forest with his family. “As a child, I remember the first time I saw Babban. We were leaving for an evening safari, and I saw this forest guard in a uniform, standing with a gun,” Soni says. By the time he was certain that he wanted to be a filmmaker, Soni knew it was Babban he would dedicate his first big project to. "When we were back from the safari, the same person was dancing in a salwar-kameez around the bonfire,” he recalls witnessing the birth of Babli by night, which is also the name of his 24-minute-long documentary longlisted for the BAFTA Student Awards in the documentary category this year.

In a way, Soni has grown up with Babban, a Muslim transperson shunned by their family to the peripheries of the forest they have made a home out of. “It was never a proposal of sorts from me that I would make this film. Just that I always knew that Babban wanted to be in a film,” says Soni. Logistically, he didn’t quite anticipate the scale of what he would embark upon, even though he had a vision in place.

After a few years of estrangement, Soni reconnected with Babban over long phone calls during the COVID-19 pandemic. They immersed themselves in conversations about documenting the life of a person who yearned to live in the body of the woman whose spirit they were born into. Babban is a dreamer. They paint their nails in the brightest red, go shopping at local markets for “frocks” that they pair with the perfect golden leggings they own. There are glimpses of Babban with the women of their family — especially the mother who can’t quite understand the reality of her child. There’s some begrudging acceptance from their kin, but an abundance of love for them from Babban, foiled by their crippling loneliness that Soni captures in his visual treatise. Babban wants to belong as Babli but finds themselves at odds with the world they were thrust into.

As a result, the greatest challenge for Soni lay in not only telling their story with compassion that entailed unlearning his urban, upper class, cis-het privileges, but also ensuring Babban's safety. “The subject is sensitive. However, one also must consider the fact that it’s being told from a place the world has zero understanding of. There are also the family members involved, and of course, the security of Babban,” Soni points out. It led him to make choices between what would make a better film, and what would be done right by his subject. In almost every instance, the latter took precedence, as Babban was actively involved in every aspect of the project, beyond acting. That journey was four years long, midway through which Babban was handed a life-altering HIV diagnosis.

“We started shooting in the monsoon of 2020 and wrapped the shoot sometime last year. There were almost 100 cuts to the film and that was a very, very challenging part of it,” says Soni, who mounted the documentary with his own money, help from his family, and friends who chipped in for a vision that became everyone’s own.

In a particularly poignant scene, Babban recalls seeing a mother elephant look out for her calves, as Babban lies supine under the sun, on the generous bark of a tree in a salwar kameez. They say, while recollecting the memory, that it brought them inexplicable comfort. For Babban, the forest is their home, a safe space; the city, a hostile territory. In that moment, one senses the inherent paradox of their existence that Soni foregrounds through Babban’s voiceover — about their hope and love as markers of resistance — and what Babban does on screen that reveals their fragility, often corporeal in nature. It’s as if they have been incapacitated by a society with a disease that operates like a metaphor for what plagues their surroundings more than them.

And yet, Soni’s gaze shatters the mirage of the parable to show the sole reality that lies at the heart of Babban’s story — a life of solitude, but one that they’ve learned to defy as Babli, who blooms like a wildflower in their chosen home of the forest, in the face of adversities.

For Soni, the documentary stems from a deeply personal need to want to better understand a person he has known for half of his life. However, what it unexpectedly brought him was healing and patience. “The worlds (of Soni and Babban) are very different, but what a place is doing for a person stays the same. So, from that point of view, it was very interesting to sort of try and externalise what that felt like,” the filmmaker says.

Now, after having also been officially selected for the New York Indian Film Festival 2025 and the Rome Short Film Festival 2024, Babli by Night hopes to make its way to India. Produced on a shoestring budget of ₹20 lakh and incubated in a homegrown South Asian community of independent filmmakers who have each other’s backs, Soni hopes for the ecosystem to offer more accessibility in the days to come. It’s the only way he can continue to make someone “feel something”, even if that's a fraction of how transformative the undertaking was for him. “It was the most beautiful process, but it felt unrelenting in some parts. However, when I finished making the film, I felt proud of it, and Babban felt proud of it. And that’s what really mattered to me,” Soni signs off.