Suggested Topics :

Tarun Tahiliani Interview: 'Serious Designers Do Not Design For Movies'

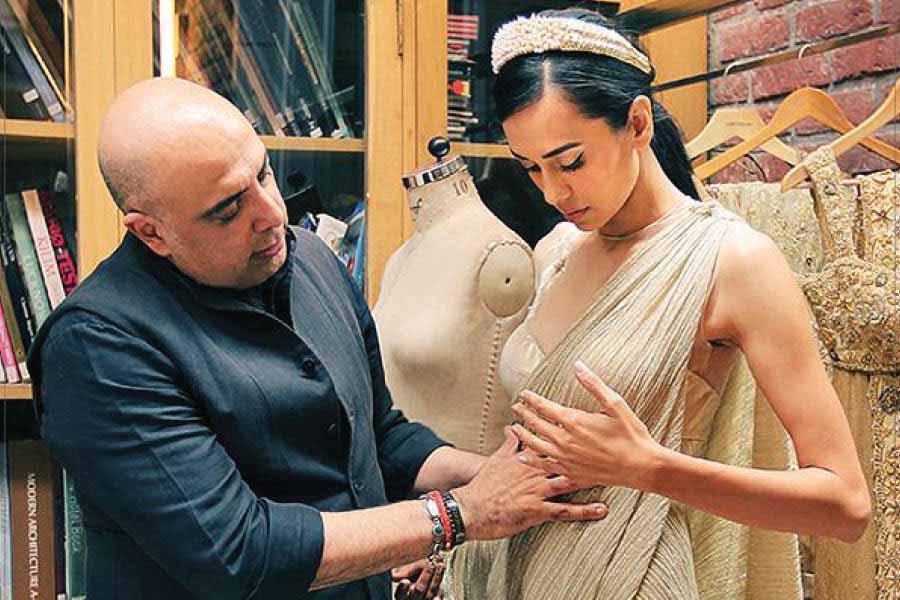

From preserving craft clusters to redefining luxury prêt, and most recently styling Janhvi Kapoor’s much-talked-about Cannes debut, the designer remains at the forefront of India’s evolving sartorial landscape.

Tarun Tahiliani’s flagship store in Mumbai’s Fort district carries the distinct scent of fabric and polished wood. The mannequins stand dressed in his signature drapes, while the high ceilings and expansive rugs give it a contemporary, yet innately Indian feel. A bride-to-be prepares to leave the store after a private appointment, as The Hollywood Reporter India finds the designer wrapping up in his office on the first floor.

Despite dressing some of the biggest names in the industry, Tahiliani confesses he prefers working with non-celebrity brides. “Am I allowed to be honest?” he asks with his characteristic, booming laugh, glancing at his PR agent who sits across the table. “She’s turning pale already!”

The designer explains that celebrity brides tend to approach their weddings as they do a character in a film — perception playing a key role. He admits, “While it’s wonderful for publicity, I think real glamour lies off-screen — in the people who live it, breathe it and pay for it.” He points out that, unlike in the West — where Scarlett Johansson can stroll through Manhattan wearing a hat — we remain far too enamoured by celebrities in our country.

Film Vs. Fashion

Ironically, despite his stance on fame and celebrity, Tahiliani has, in some way, been a part of that world. “Back in the ’80s, good Hindi movies, along with awful Russian movies came to town,” Tahiliani recalls. “I used to dub those into English for 500 bucks a day.” Tahiliani was a theatre man, reminiscing about a play he worked in with the late actor Pearl Padamsee. “The play was called Love, a trilogy that takes place on the Brooklyn Bridge. Every weekend we flew to perform in different cities. People had dinner while we did our supper theatre,” he says. “We even performed in the Central Prison in Coimbatore. Because there were no theatres there, the jailers would lay the seats, and [prisoners] would be locked up. The town would come to watch, and then the jailers would put the seats back,” Tahiliani explains, adding, “Jugaad — that’s how India functioned.”

During one such performance, he discovered designer Asha Sarabhai’s pieces, which were in collaboration with Japanese designer Issey Miyake. “I went to see her in Ahmedabad and then (his sister) Tina [Tahiliani Parikh] married Suhrid [Sarabhai’s] cousin, Vinay [Parikh].” Despite his ties to film and theatre, Tahiliani has never considered pursuing costume design. “Back then, Meena Kumari designed her own costumes for Pakeezah, and they were fantastic. But fashion and movie [costume] design are two different things,” says the designer. “An odd movie is done — like [in the ’80s] Jean-Paul Gaultier did The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, or Giorgio Armani did [Richard Gere’s costumes in] American Gigolo — because it’s funky.”

But Tahiliani sees fashion and costume design as distinct worlds, often confused, leading to the latter being mistaken for the former. “But serious designers do not design for movies,” he asserts. He agrees that when a celebrity like Janhvi Kapoor wears and styles an outfit, it resonates with the modern Mumbai woman, which then leads to a surge in the copy market.

“Roaming around Surat, my own people have shown [copies] to me while sourcing for Tasva (his menswear brand). I said, that’s a TT copy, don’t you have any shame? At least hide it!” Tahiliani says with a laugh. “They were all flustered. But I thought, should we carry our own copies?” The designer knows there’s no stopping it, so his defence is to create pieces so intricate and masterfully crafted that those who can afford them will never consider settling for imitations.

India Modern

The journey to creating such one-of-a-kind pieces began with his brand Ahilian and the multi-designer store Ensemble in 1987, which was later handed over to his sister Tina in 1990, when he left to study at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York.

“My father was quite distraught when I started Ensemble — said I was becoming a tailor,” he recollects. Selling oilfield equipment by day, he’d work at his studio three evenings a week. And by studio, he means a four-storey walk-up without an attached washroom.

“We’d work on a chatai (straw mat) because there was no furniture. Tailors would come to take the fabric. We didn’t have mannequins, so we’d put loose kurtas on this very thin peon [who worked there], and he’d walk up and down. And as we worked, we’d get batata vadas from downstairs.”

The early designers to showcase at Ensemble were an eclectic mix. Rohit Khosla, a Kingston University graduate, had worked with Versace and was Albert Nipon’s head designer in New York. Abu Jani [and Sandeep Khosla] designed for a small Juhu label called Mata Hari, while Rohit Bal was just starting out, supported by his brother’s export company. American designer Neil Bieff was a Bergdorf Goodman favourite, and Anita Shivdasani [with Sunita Kapoor] contributed production expertise. Even the legendary Zandra Rhodes joined in, drawn by the beauty of Indian craftsmanship.

It went “viral” — thousands of boutiques emerged, and ready-to-wear fashion took off. Years later, in 2003, Tahiliani became the first Indian designer to showcase at Milan Fashion Week with ABFRL (Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail), presenting a prêt collection ahead of its time. Today, his latest ready-to-wear venture, OTT, redefines luxury prêt-à-porter for the modern woman. Tahiliani describes Ensemble’s fashion shows as legendary. He recalls, “It was almost a riot, I remember a woman pulling out a lipstick and slashing somebody.”

He also mastered his embroidery skills in those early days. Growing up in South Bombay near the Taj Palace Hotel, he spent years in Parel, learning the craft from master embroiderers. “Every time I wanted to see an embroidery swatch, I’d get into a black and yellow cab and in that ghastly traffic, go four streets in, climb up two flights and in a small room I’d find 30 embroiderers.” He recalls how tough it was and commends his fellow designers Manish Malhotra and Abu Jani and Sandeep Khosla for having been through the rigours as well. “Schlepping all over the city in non-air-conditioned cars and slums because we loved it.”

After studying abroad and visiting studios like Perry Ellis in the US, he realised he needed to dream bigger — beyond the sweatshops and Parel bylanes. In Paris, fashion studios stood on the best streets — Chanel behind The Ritz, Yves Saint Laurent on George V — while in Mumbai, they were relegated to industrial pockets. “So, I moved to Delhi,” he says. “Also, no fashion capital exists without a summer and a winter. You remove Bollywood from Mumbai and the influence it has…,” he trails off.

The designer points to swatches lining his office wall, including one from Radhika Merchant’s pre-wedding lehnga — intricately embroidered yet astonishingly light. “That’s technology,” he says. “Luxury is what you feel on your skin.”

Speaking of luxury, Tahiliani grew up in a socialist India, looking over the wall. The rich women of the time would buy Swiss silks to pair with a kurta-salwar and tie a scarf. They were more Indian since people didn’t travel much. “But it’s a much more global world today.”

The designer pulled out the modern sketches he made for the bride who had just left. “This could be an Elie Saab creation, worn anywhere in the world. But it takes real technique — under-construction, padding, boning, Victorian corsetry — to make it all stay in place.”

“So, while it’s Indian, it’s contemporary. I grew up in South Mumbai; I’ve been to Campion [School]; I studied in America; I’m not looking to pretend that I’m overly ethnic. I’m more Indian at heart than most people I know, but I don’t have to show up in a sherwani.” In other words, “India Modern”, as is in the title of his book published in 2023.

Sustainability and Inclusivity

A major force in the industry, Tahiliani had also joined six other designers and a businessman in 1999 to establish the Fashion Design Council of India (FDCI).

But back then, 40 years ago, prêt didn’t exist in India. People relied on tailors, valued their clothes, and embraced sustainability. Even snacks were freshly made — Tahiliani recalls buying wafers from a Colaba stall each evening. Soft drink bottles were returned in crates, and disposable income was scarce.

“Last night, I saw these Maharashtrian women, running around with their saris pinned in place, with their traditional bindis and flowers. They’re true to themselves,” says the designer, a quality lost to the habit of never repeating clothes for the sake of an Instagram feed. Though he found a solution: His studio is happy to design different cholis (tops) and palazzo bottoms for clients to repeat their lehnga sets in new ways. But sustainability isn’t limited to the environment — it extends to the people. The Tarun Tahiliani brand, along with its subsidiaries, has a workforce in the thousands. Beyond in-house staff, they’ve trained clusters of craftsmen, preserving traditional skills.

“After COVID-19, Mumbai saw the worst migration,” Tahiliani reflects. “That’s when we started opening clusters. Now, many work in their villages and they’re no longer migrant labour.” The designer is happy to note that they don’t have to leave their families behind for long. Now, his fight is against automation. He says, “With Tasva, I say we’ve got to keep manufacturing in [Varanasi].”

Tahiliani is equally considerate of his audience. When faced with an overcrowded venue last year, he pulled off the impossible: two shows in one night. “I had no choice because there were 300 people screaming outside,” he reveals. “The RSVPs were overbooked. The easy thing would’ve been to say sorry, but people braved traffic and were upset.” It was a nice, though rather expensive gesture — costing the designer roughly ₹40 lakh for the extra 20 minutes. “But fashion has a bad reputation of being snooty and I don’t like that.”

His studio too, has been a safe space for people to work in. “When the Bombay riots happened [in 1992-93], the Hindus locked the Muslims in the studio and got them food. Also, [all] genders and [types of] sexuality are welcome,” Tahiliani explains. “Fashion has always been inclusive. The only thing we’re not inclusive of is shrieking tempers, which we try to control!” The designer found himself fighting a body-shaming allegation a few years ago, to which he responded, “It’s a business, and the sari is the most inclusive thing you can wear. I may not have every size ready-made, but if you give me your measurements, I’d be happy to make it.”

The most important thing to sustain, however, is the dream. As Tahiliani expands with a new store in Dubai, he reflects on the real challenge. “Opening a store is easy. Sustaining it — that’s the hard part.” He breaks it down with a business mindset: Trunk shows gauge demand; local marketing is key. Grounded in character and guided by comfort, Tahiliani’s pieces reflect a thoughtful blend of style and ease — where fashion isn’t just worn, it’s lived. But that’s no simple task; signing off, the designer admits, “I’m telling you; I have no life.”