Suggested Topics :

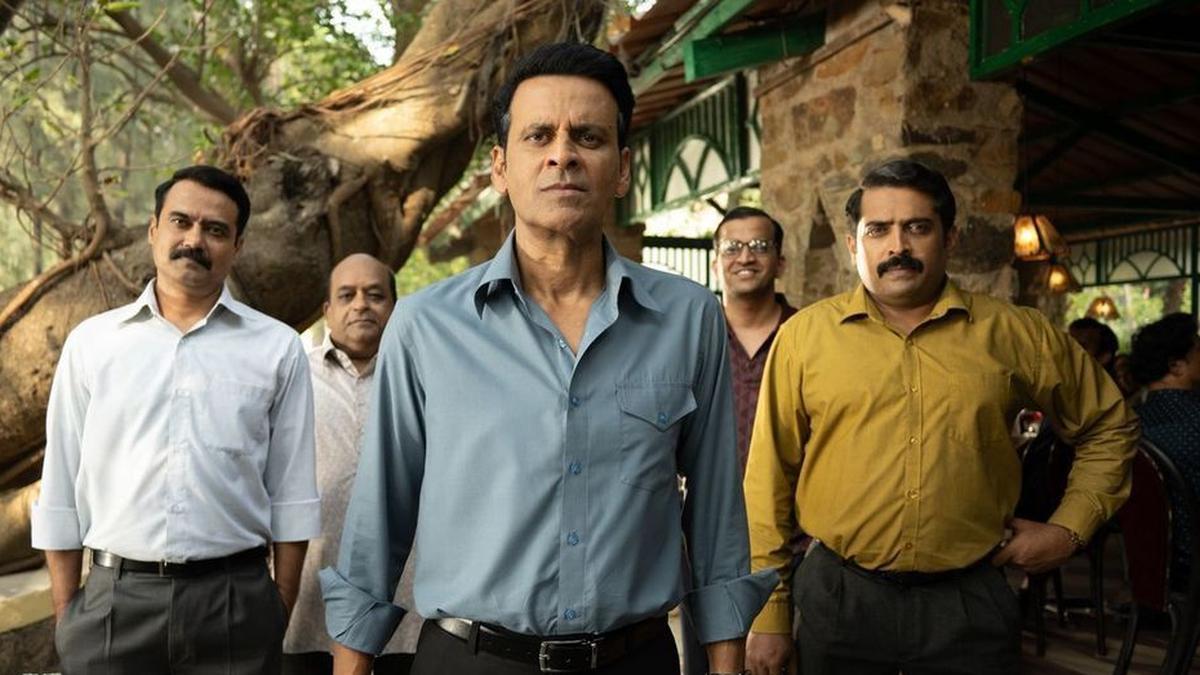

‘Inspector Zende’ Movie Review: A Manoj Bajpayee Special That Injects History With Humour

Inspired by the real-life story of a supercop tracking down a notorious killer, 'Inspector Zende' stands out because of the genre it chooses

Inspector Zende

THE BOTTOM LINE

A clumsy but watchable cop comedy.

Release date:Friday, September 5

Cast:Manoj Bajpayee, Jim Sarbh, Sachin Khedekar, Girija Oak, Harish Dudhade, Bhalchandra Kadam, Bharat Savale, Onkar Raut, Nitin Bhajan

Director:Chinmay Mandlekar

Screenwriter:Chinmay Mandlekar

Duration:1 hour 52 minutes

In the Netflix streaming canon, the film Inspector Zende begins where the series Black Warrant ends. It’s 1986, and deadly “Bikini Killer” Charles Sobhraj escapes Tihar jail after drugging the whole prison on his birthday. The six-episode drama hinted at how he managed to break out. The guards were too busy being the protagonists of their own stories of systemic struggle. Sobhraj, a peripheral figure in his decade there, simply took advantage of their main-character energy. Far away in Bombay, waiting in a milk queue, Inspector Madhukar Zende (Manoj Bajpayee) hears the news bulletin on a radio. By the time the others in the line look at him, he’s already gone — like a middle-class superhero looking for a phone-booth to don his cape. Only here, the booth is his modest family room in a chawl, and his cape is the Bombay police uniform. He expects a call any moment, given that he’s one of the few cops to have previously nabbed the criminal.

Chinmay Mandlekar’s film may exist in a shared universe, but the genre belongs to the opposite end of the spectrum. Inspector Zende is a crime caper — a deliberately over-the-top and whimsical take on real-world characters (Sobhraj here is ‘Carl Bhojraj,’ in case you’re wondering) and events. You don’t often see comedies made out of inspired-by-true-events stories; heroism and underdog narratives tend to be distinctly grave themes. Particularly if it’s a cat-and-mouse game between actual cops and a slick criminal who’s scheming to escape the country. The tone is surprising, disarming almost, and it works as much as it doesn’t.

For starters, it finds entertainment in those same systemic struggles without trivialising them. The main character energy that became the undoing of the Tihar jailers from Black Warrant is weaponised here. Pressure from above is absorbed by a good-natured DSP (Sachin Khedekar) who secretly backs Zende’s motley team. Their grassroots challenges are turned into genre fodder. For instance, when Zende’s expecting his call, he must first get an oversmart electrician to fix the landline at the police station. Later on, covert meetings happen at his flat to plan their undercover mission (one of them sits on a toy bicycle due to the space-crunch). At another point, Zende is so engrossed in taking orders that he absent-mindedly follows his swimsuit-clad boss to the top of a diving board. The credit greed and jurisdiction war between rival police forces play out like cultural shorthand: Delhi police entitled, Goa police lazy. In a dramatic film, this would’ve looked hagiographic, but the levity takes the edge off. Even the pro-Maharashtra subtext comes across as playful, not smug or dangerous.

The team’s budgetary constraints in Goa, too, become a source of both realism and jest. One of the members is an accountant who keeps fretting about receipts, invoices and cash flow; the viewer remains conscious of the bills (those 1980s bar rates are mouth-watering). The tension of the mission stems from how they’re running out of money; it’s a race against bureaucratic blocks as much as time. There’s something endearing about seeing a cartoonish team actually do their job — against the odds of the genre and audience perception, not just the circumstances. You don’t expect them to be resourceful because of how they are presented. Bajpayee’s The Family Man-coded performance goes a long way in humanising this tone. The actor keeps the film fluid enough to shuffle between pitches without downplaying the urgency of the chase. His presence is the reason a desperate scuffle with the wanted criminal at a wedding reception can unfold like an accidental dance sequence (with the ‘twirls’). His reactions complete the running joke of an un-smiling subordinate, Jacob (a solid Harish Dhudade), whose deadpan face becomes a nod to genre trappings; it’s like Jacob hasn’t gotten the memo that he’s in a comedy and not a pensive procedural.

The drawbacks of this treatment, though, reduces Inspector Zende to a middling watch. The period comedy uses pulpfiction — a '70s background score, customary references to Amitabh Bachchan and Dev Anand and Rajesh Khanna, those stagey outdoor shots — very differently from cinephile-directors like Sriram Raghavan and Vasan Bala. It’s the Bollywood of an era people like Zende have grown up following, but the style here is entirely cosmetic; it disguises a lack of substance in the writing, detailing and production value. The nostalgic music allows most films to get away with mediocre craft (and, in this case, tacky CGI backdrops). Add the Netflix-coded colour palette and lighting (I can’t handle those radioactive reds, blues, purples and pinks anymore), and it looks like more of a corporate decision than a creative one.

Some of the gags don’t land either. Zende’s long interrogations of two crooks in Panvel go nowhere: neither quirky nor clever. There’s also the paradox of casting Jim Sarbh as the French-Indian killer. Unlike the actors (Randeep Hooda and Sidhant Gupta, to name a few) who’ve customised the eccentric persona of Sobhraj over the years, Sarbh is so tailormade for the role that the film takes him for granted. It’s satisfied with his physicality alone, reducing the character to a filler in Zende’s quest; it ends up fetishising the villain — and his killing spree — to sell the stakes. Naming him Bhojraj may provide the creative license, but it doesn’t smoothen the inconsistency of the storytelling. These little spurts of sobriety in the unserious movie extend to the portrayal of Zende’s domestic life. The TV-soap sincerity of Zende’s marriage — missing his god-fearing wife (Girija Oak) keeps him honest — becomes his superpower; he’s the one who deduces that Bhojraj might be found at the only Goan bar he can phone his American wife from. At times, however, it looks like the film reverse-engineers Zende’s scenes as a committed husband to arrive at the point where he guesses Bhojraj’s impulses and whereabouts. The design need not be so visible.

The tonal dissonance is most evident in the redemption arc of Zende’s constable, Patil (Bhalchandra Kadam). A scene where Patil freezes on spotting the killer on a ferry results in him being ‘disowned’ by a disappointed Zende, who calls him a coward. It’s a strong moment that, for once, alludes to the fact that cops are human. In a pacey thriller, Patil would’ve perhaps sacrificed himself in the end to prove his worth, but this film is so determined to be flimsy that his track is resolved in a slapstick manner. The patriotism of these unlikely heroes comes across as an add-on package, almost as a last-ditch reminder that laughing at the characters cannot come at the cost of respecting them. It’s like watching that jovial and attention-seeking uncle at a wedding who becomes somber without warning. Particularly when he’s trying to show that he’s an upright citizen beneath the nostalgia and colour. But it’s not a deal-breaker, because most men his age don’t even have a sense of humour. At a time when Bollywood theatricality is often used to manipulate history, I’ll take a story that uses clumsy wit to conceal emotions and cultural agendas. Most (inauspicious) days of the week, at least.