Suggested Topics :

'Turtle Walker' Documentary Review: Taira Malaney Destabilises the Boundaries Between Fiction and Nonfiction In Myth-Making Doc

The film is backed by Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti, with James Reed, the award-winning co-director of 'My Octopus Teacher' as an executive producer.

Nature documentaries thrive on a brimming sense of wonder and intimacy—of the world that is out there, and of a person who, with uncritical love in their heart and irrational courage in their spine, builds that bridge between this world and that. Documentaries like My Octopus Teacher and Fire of Love thrive on this doubleness—the too large pressing down on the shoulders of the too small.

Taira Malaney’s Turtle Walker, chasing the path laid out by Satish Bhaskar, who kick-started an interest in sea turtle conservation in India, is an attempt in that direction—but it gets so caught up in the myth of its protagonist, it often forgets this intimate quality, swapping it for the cinematic, instead.

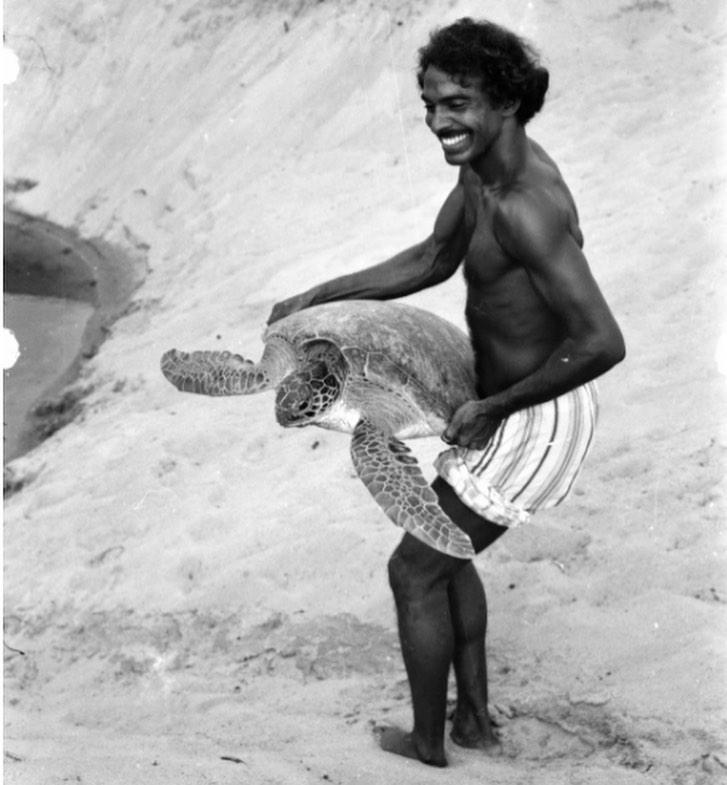

Bhaskar lived a full life—he passed away in 2023—spending over 19 years, between 1977-1996, surveying over 4000 of the 7500 kms of the Indian coastline (since then, the coastline has been re-measured, coming up to around 11,000 kms). He spent five months by himself in Suheli, an island in Lakshadweep, where he was stranded studying turtles, sending love letters to his wife, Brenda, by throwing bottles with messages into the swelling sea. One of these bottles traveled 800 kms to Sri Lanka, where a fisherman found it, put it in an envelope and posted it to his wife. Finally, Bhaskar was picked up by a Lighthouse Department Ship. Later, he spent seven months on South Reef in Andaman chasing the Leatherback sea turtle until he got diagnosed with Trigeminal neuralgia, causing him severe pain in the eyes and head. He had to retreat.

This film begins in 2018 in Goa—where Bhaskar, through tight close-ups, speaks to the camera about his life. Malaney recorded over 26 hours of footage of him extensively recounting those years collecting turtle data. Bhaskar’s meticulous notes helped.

Malaney, however, makes a curious choice to dramatise the narrations, by shooting with actor Rohan Joglekar, who plays the young Satish Bhaskar—the gaze is exact, though Joglekar’s nose is far sharper. By doing this, Malaney has foregrounded the limitation of both the documentary format, and her documentary film. More interested in the mythical past of its protagonist, than their shapeless present, the documentary becomes not a truth-telling, but a myth-making engine; it delights in the retrospective mode, not prospective.

This decision gives the film some of its most potent, profound images, say, of young Bhaskar, with a flashlight, coming across a Leatherback so huge, he is dwarfed by both its image and its impact—the first such sighting of this turtle in India. But it also completely destabilises the point of the documentary form, by pretending the border between fiction and non-fiction is a formality that one can toy around with.

The playfulness is not a problem. Much ink has been spilled over this division between fiction and non-fiction, with questions around how much a filmmaker can intervene in a story, how much polish can they summon, etc.

The problem is when this pretense leaks into the way the film thinks about Bhaskar—who becomes hollowed out of his personhood, becoming a sparkling shell of spectacle, instead. As though they have used the three-act structure to make sense of his life. For example, the documentary only seems interested in his hunger when it causes a moral crisis in him—making him eat turtle eggs. He spends 150 days on the island of Suheli, and the film did not once ask, where does the man get his nutrition from? How does he bore?

Similarly, the film is interested in his wife, Brenda, only as a set-up to land the punchline of the letters in a bottle. The gaze feels so curated and tightly structured, it feels like life, not just being re-organised on the editing table, but being lived on it. It is a tragedy when people become protagonists—a shadow of themselves, made palatable, polished, and purposeful. When the film lets its gaze wander, Bhaskar and Brenda walking, the latter waddling, the former holding on lightly, or when it lets him stare at her while she speaks—the whisper of another film can be heard.

Turtle Walker loops us back to the present, nudging Bhaskar to take one more trip to the Andaman and Nicobar islands, to see how it fares in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami—but this, too, is an obvious set-up, where the documentary is prompting the protagonist into action, not capturing an action that would exist otherwise. Why did it take so long for Bhaskar to finally return to the islands? The film is interested in the story-beat of his return—that should be enough.

The film has a formidable polish. After all, it does have James Reed, the award-winning co-director of My Octopus Teacher as the executive producer and Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti’s Tiger Baby—which also produced the documentary In Transit—as a producer. The top shots, and underwater footage in clear azure waters feel edenic, untouched by a human desire to control. The cinematographer, Krish Makhija, uses infrared cameras for filming turtles, so they wouldn’t get disturbed. Rare archival photographs of Bhaskar meticulously documenting his trips—around 300-400 scans—keep rupturing the film’s fictions. The sound design is thick and sensuous, you can feel the pain in the turtle’s eyes as they are birthing eggs, because the sound of them blinking with wet eyes has been captured on sound—a pchh.

Similarly, their chattering, the sound of sand being splashed by their flippers, breath leaving the holes on their nose, and even the dropping of wet eggs—these build atmosphere. (A foley studio and foley artists have been credited in the film’s end scroll, so how much of the sound is documented and how much is staged is not clear.)

At the end of it all, the question remains—is the life-staged meant to emphasise the life-lived, or does the film run in the opposite direction? That when you think of Bhaskar, you think not of his story, but of his youth, overwritten by the striking face of Joglekar, full of passion, full of doubt, full of a life that has been lived forward only so it can be told backwards.

Turtle Walker had its World Premiere at DOC NYC 2024 in New York and the India premiere at the International Documentary and Short Film Festival in Kerala (IDSFFK)