Suggested Topics :

Ahead of 'Thamma', Ayushmann Khurrana's 10 Best Performances, Ranked

With 'Thamma' releasing on October 21, here are Ayushmann Khurrana's 10 most effective performances.

Most actors look for a home in the Hindi film industry; some build their own. Since its arrival in Vicky Donor, the Ayushmann Khurrana School of Storytelling has become an affordable institution that bridges learning and entertainment; stardom and social value; maturity and boy-next-door anxiety. The school has screened applications, sworn by its syllabus, stayed accessible and stubborn in the face of constant flux. At times, Khurrana’s image as the principal who cares too much feels like a safety net; the wokeness tends to flatten the ambition to take risks, push the boundaries of the craft and try new things. At times, this image is also the reason he has survived, thrived, stumbled and led the secondary tiers of fame between the Khans, Deols and Shroffs.

It’s easy to take his presence on camera for granted because there’s no false promise. It’s a sweet spot of sorts: you can’t really think of a film where Khurrana is memorable precisely because you can’t think of a film where he isn’t. He’s always there, as an antidote to North Indian masculinity — it’s up to the makers to either employ or challenge his genre. It’s no coincidence that some of his best work has happened in movies where he’s simply acting, not performing; where he’s emoting, not pandering to emotions.

13 years and 20 films later, the upcoming Thamma — a vampire-themed Maddock Universe horror comedy — is his biggest ticket yet. Regardless of the result, it feels like the culmination of being visible and invisible at once; of following the trends and being followed by an industry that’s averse to originality and seduced by scale. On the eve of his 21st role, it’s a good time to ‘cut to flashback’ and recall a career that’s been on the brink long enough to make it a home. Here are 10 of my favourite Ayushmann Khurrana performances, ranked in ascending order:

10. Article 15 (2019)

I remember watching Article 15 during the Anubhav Sinha Renaissance Era (post Mulk) and thinking: what a clear-minded social drama. Even better, it opens with notes of Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ In The Wind, as a car from the city snakes towards a hinterland full of grassroots bias and caste-based violence. Over the years, Article 15 has admittedly not aged well, given the urban-saviour gaze that was so obvious in its first frames. In fact, I suspect my fondness for the film stemmed from this very gaze: a privileged and upper-caste male writer enjoying a perspective he identifies with. But Khurrana’s performance as the St. Stephen’s-educated IPS officer posted in rural Uttar Pradesh doesn’t pretend to know better. Unlike the God complex heroes popularised by Akshay Kumar back then, Khurrana offered a middle ground in terms of the protagonist’s ready-made wisdom and righteous rage. Dylan’s music is initially his way of transcribing the oppression he has studied in books and newspapers — until silence becomes his soundtrack in an India that resents his idealism. It’s a turn that allows the film to exhale between its bouts of preaching to the choir.

9. Shubh Mangal Saavdhan (2017)

Shubh Mangal Saavdhan is Peak Ayushmann Khurrana. It’s all colour and contrasts: loud, smart, funny, preachy, progressive, satirical, unsubtle, a mansplaining takedown of toxic masculinity. As a red-blooded Delhi boy whose impending marriage is derailed by erectile dysfunction, Khurrana’s exasperated body language becomes the top draw of a story that thrives on a quintessentially Indian lack of boundaries, the involvement of families in ‘intimate’ problems, and a perfect supporting cast. You can feel his hubris turning into debris, bit by bit, as his private condition is inflated into a public mission. The writing platforms the actor and his strengths: the trademark scowling, the sighs and reaction shots, the rudeness that softens, the spatial awareness, the middle-class urge to live in the cracks of love stories. Of course the film insists on the usual transformations and monologues and abrupt tonal shifts, but not many mainstream Hindi star-actors have an entire genre named after them the way Khurrana does. Diversity is nice, but so is the ability to be different versions of the same person.

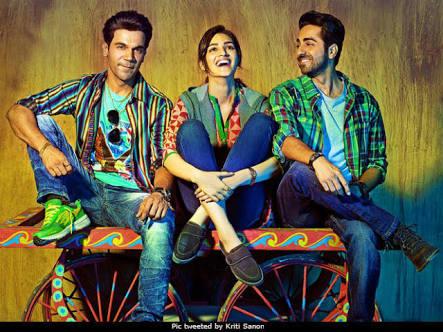

8. Bareilly Ki Barfi (2017)

2017 was a banner year for Khurrana, and it’s fitting that he starred as yet another unlikable and self-centered beta-male writer in the year’s definitive small-town comedy only to cede the spotlight to another actor. Rajkummar Rao took the plaudits for the crowd-pleasing role as the performative nerd in a love triangle. Khurrana, however, shows a penchant for blending into crowded movies instead of standing out and stealing the spotlight. He’s had a knack for this across his career — evident from how we can neither find a mind-altering Khurrana character nor a mind-numbing one (though Dream Girl 2 comes close). What you see is sometimes what you don’t get. He is effective in intangible and consistent doses here; his Chirag Dubey is no Pritam Vidrohi or Bitti Mishra in the pop-cultural canon, but there’s something about him playing a shuck-boi who is ready to be schooled, fooled and enlightened for the sake of Bollywood infotainment. It’s a case of main-character energy disguised as all-character energy.

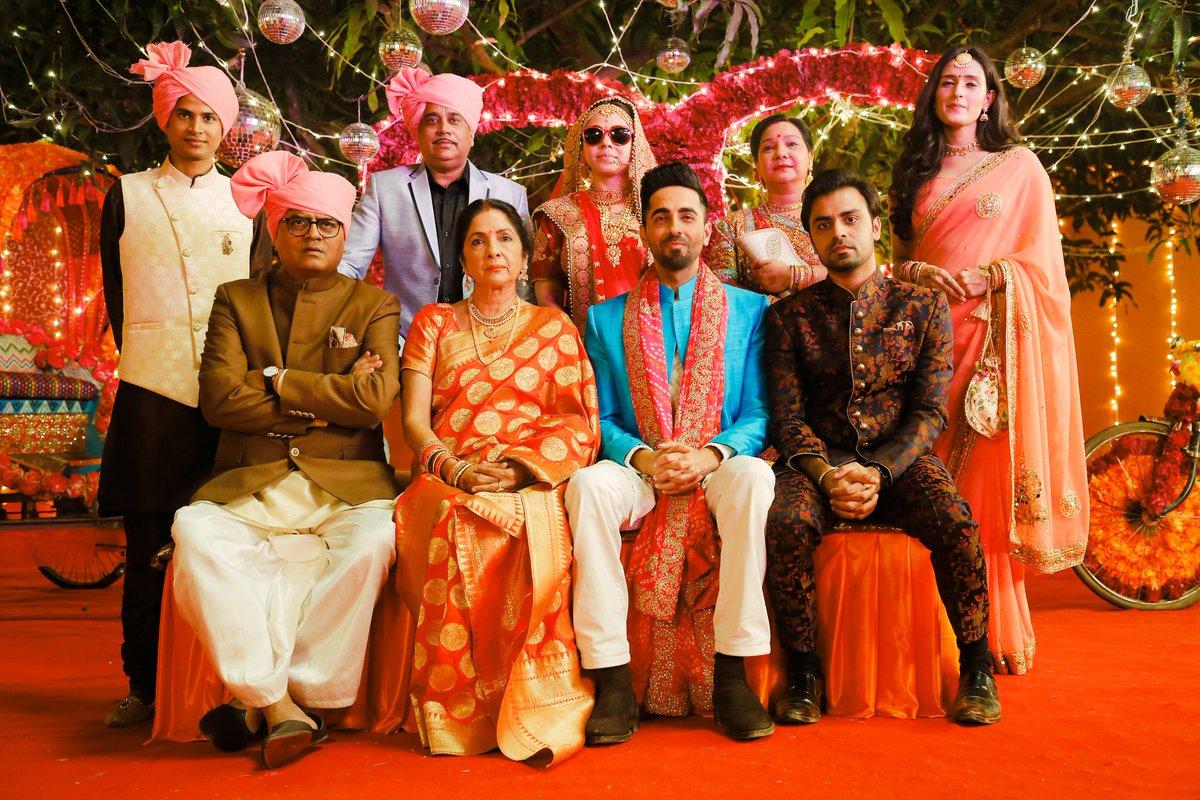

7. Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2020)

More than one word separates Shubh Mangal Saavdhan (2017) from its spiritual sequel: a gutsy and rare gay romcom that expanded the vocabulary of commercial Hindi cinema in the early days of the pandemic. A Khurrana multiverse bristles in this film, where the Badhaai Ho parents (Gajraj Rao and Neena Gupta) reverse and humanise a formula that resists binaries and broad strokes about free love in the age of repression. The themes extend beyond the obvious to explore the moral tension between generations, the trauma inherited by children in dysfunctional families, the paradoxes of parenthood, and the burden of masculinity in a patriarchal society. Some of it is clumsy and calculative, but Khurrana’s courage — as the better half in a couple where someone else is a conflicted protagonist — shapes the levity of a heavy-hearted and thorny narrative. His Kartik Singh is not even the central character with the intolerant family, yet the actor’s ‘niche’ as a preacher in an age of provocateurs tides the film over and allows it to punch beyond its social footprint. It’s important, yes, but it’s also good storytelling with fine performances. Imagine that. SMZS walked so that Badhaai Do could sprint.

6. Dum Laga Ke Haisha (2015)

A decade ago feels like a lifetime in the India of 2025 — long enough to forget that the ‘hero’ of its most subversive romcom was essentially a right-wing chauvinist so caustic and entitled that only a very persuasive performer could have provided him a redemption arc. Khurrana nails the challenge in Sharat Katariya’s wonderfully textured and witty 1990s-set story. Largely remembered for Bhumi Pednekar’s self-assured debut and some Kumar Sanu nostalgia, Khurrana’s Prem Prakash Tiwari remains the patriarchal-but-flexible heart of the Haridwar-based marital dramedy. The holy setting is the star in more ways than one, shaping the man’s relationship with his own small-mindedness while never denying any of them the capacity to change and unlearn. Khurrana pushes the character to the point of no return in terms of inherent bigotry, but then manages to salvage a comeback without hijacking the limelight. A lot of the film is cleverly written and disarmingly frank, so it’s like watching an oblivious mass hero getting educated by love. The feel-badness of a nationalist video-cassette shopowner is so strong that the feel-goodness just hits different. After all, secularism is the ultimate reward.

5. Doctor G (2022)

Speaking of unlikely redemptions, all the Khurranaisms are there in Doctor G. The ‘condition’: an Indian man studying to be a gynecologist. The wokeness: he has a progressive mother and falls in love with a Muslim girl. The flaws: he expects better treatment from his ex because he’s not a problematic man (“like Kabir Singh”). The casual sexism: he judges his mother for being on a dating app, and dismisses his own prospects because he’s a benevolent man in a female-dominated field. But this is only the first half. The underrated victory of Doctor G is that it becomes an Ayushmann Khurrana movie that critiques and upends previous Ayushmann Khurrana movies — and his performance riffs on the atonement. It’s not done in a smug and self-reverential studio-in-joke way either: his character, Uday, is simply not allowed to use the ‘setting’ as a prop to transform himself. There is no sudden light. There is no sharp remission. It takes a fair bit of resolve to hold your own in a story that defies a trope-generator legacy — to be an unheralded hero who doesn’t mind interrogating his own heroism.

4. Vicky Donor (2012)

Never has the punchline of North Indian virility been so…watchable. Khurrana’s clutter-breaking debut is the film that became his cape as well as his kryptonite. The Shoojit Sircar-directed, Juhi Chaturvedi-written movie is a charming cross-cultural romcom that doubles up as a sperm-donor caper in a country that drinks humour like a shot of tequila to soften its inhibitions. Besides the stealthy deconstruction of societal stigmas and ‘taboo’ topics, the film infuses the reality-show-coded freshness of Khurrana into a story that can’t afford to be familiar. It’s a performance and character without baggage, before the patterns and tics and little affectations became the currency of a commercial legacy; the protagonist was an alt-masculine painkiller in a landscape that created space for most signatures to co-exist. It helps that the balance between the cultural and the personal — the commentary and romance — is something that precious few satires since Vicky Donor have pulled off. Those were simpler days; a versatile Annu Kapoor became the toast of the nation again, the film-makers broke out and went on a hot streak, and Khurrana and Yami Gautam’s unconventional first innings became the selling points of a stacked year for Bollywood.

3. An Action Hero (2022)

There’s something poetic about a great Akshay Kumar cameo in an Ayushmann Khurrana film that has not one message to give. They bump into one another on a flight in which Khurrana’s character — a Bollywood superstar who has accidentally killed an arrogant fan — asks for advice from a wary Kumar. The veteran’s reaction is one of many golden moments in Anirudh Iyer’s severely underwatched (the word “underrated” is off-limits) meta comedy that’s a morbid satire on fame as well as a slick action thriller about a desperate hero and grieving gangster. There’s no ‘commentary’ as such, but if you really stretch it, the timing is uncanny. Khurrana plays someone who symbolises a flawed Hindi film industry trying to survive at a time Bollywood became (and still is) India’s favourite whipping kid. He does have the last laugh (or cough), and to the actor’s credit, he treads the thin line between spoofy and serious without breaking a sweat. As a social hero in the role of an on-screen action hero forced to become a real-world action hero, Khurrana is surprisingly versatile. He could have overcooked the tone, as could the film, but both show restraint to deliver a satisfying genre send-up that bats for Hindi cinema in the most un-Hindi-cinema manner. Its box-office failure only reiterates the ‘message’ — but I fear it might be to Khurrana what the heartbreak of Jagga Jasoos was to Ranbir Kapoor.

2. Andhadhun (2018)

Who knew another messageless but not meaningless Khurrana performance — just pure Raghavan-esque suspense — would be so thrilling to watch? I spot a trend. In the peerless Andhadhun, he plays a liar who is addicted to the truth of fiction. As a Pune-based pianist who pretends to be blind only to ‘see’ things that tragically and hilariously test his resolve — a gory crime, a sociopathic woman, an organ-harvesting scam — Khurrana brings the right cocktail of greyness and nerve to a role that’s all gait and moral conflict. The viewers become co-conspirators in a film that expertly employs sound, the inner conceit of storytelling, and humanity itself to tease our notions of how a dark comedy should look. The second half chooses a difficult direction, but in no way does it lessen the arc of a struggling artist whose plan to exploit the way the world perceives — and sees — art is swallowed by karma. In Khurrana’s able hands, the character speaks to more than the plot he shapes: he’s just an obsessive musician standing in front of his craft, asking it to love him. It’s both perverse and inspiring to detect just how far a striver is willing to go; he can’t change his talent, so he changes the lens through which his talent is judged through.

1. Meri Pyaari Bindu (2017)

Commentary who? Abhimanyu ‘Bubla’ Roy is perhaps the only Ayushmann Khurrana character who writes a story for himself: not for society, not for the audience, not to assuage egos, not to tell but to feel. As a popular pulp-fiction author whose career becomes a post-script to heartache, Khurrana subverts the pain-births-art trope with a performance that yields a romantic hero who uses words as a tool for reckoning rather than closure. The Great Expectations-coded film is not named after him, but it’s named after the memory and male interpretation of the “manic-pixie dreamgirl” who loved and left. The otherwise-restless actor keeps it still and poignant, resisting writerly angst to craft a coming-of-age arc in which acceptance becomes the language of love. Not to mention the fact that Meri Pyaari Bindu did Kolkata and its quirks back when Bengali-flavoured Bollywood was more than just an aesthetic. He’s so earnest as Abhi that one can rationalise Parineeti Chopra’s over-the-top titular character as a figment of the writer’s imagination — he ‘wins’ the moment he sees her as a person and not a concept that writers are wired to sentimentalise. There is no “what if”; it’s almost unsettling to see a mollycoddled Indian man with no regrets. In other words, imagine a social-message drama in which the social message is unrequited love.