Suggested Topics :

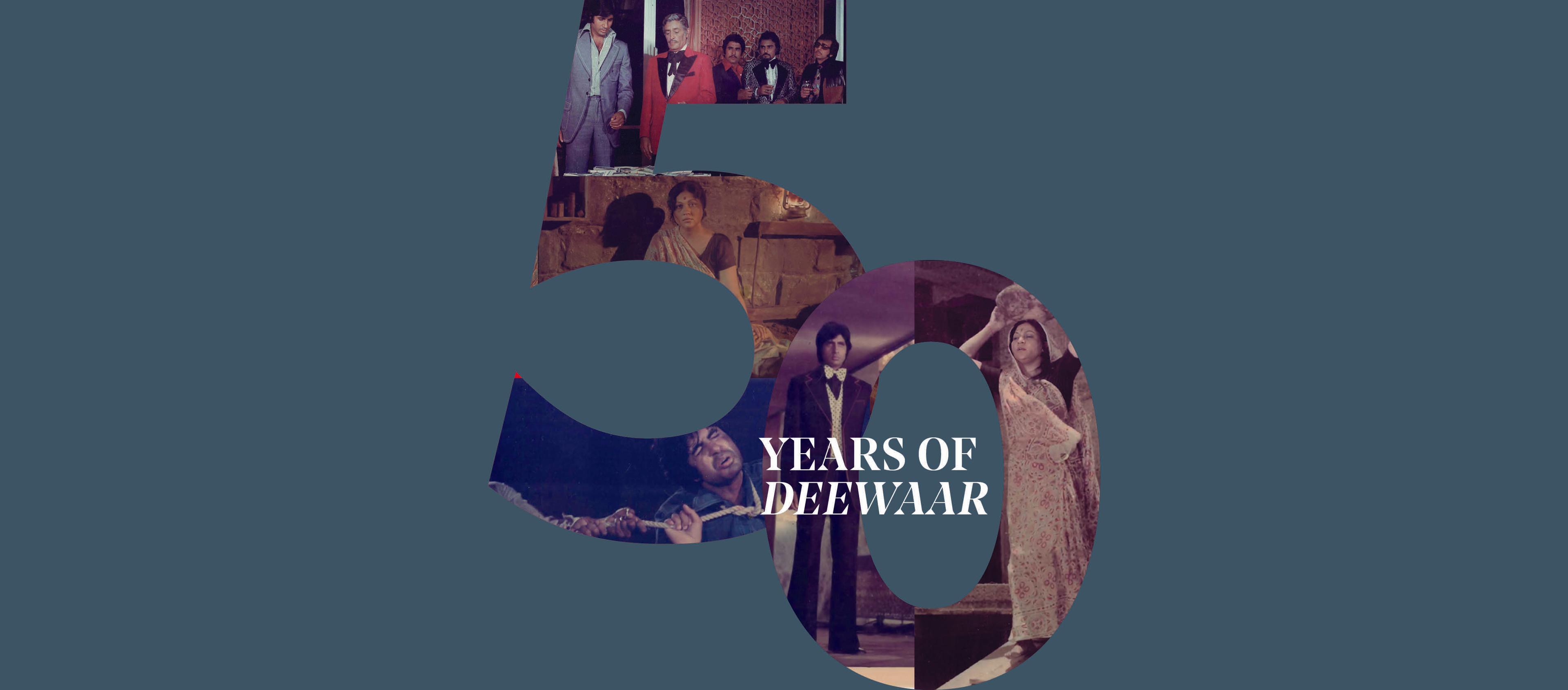

'Deewaar' Turns 50: Amitabh Bachchan, Salim-Javed, and the Birth of the New Bollywood Hero

Even after half a century, 'Deewaar' remains a landmark in Hindi cinema, masterfully marrying themes of moral ambiguity, fractured kinship and sociopolitical unrest into an enduring archetype of modern heroism.

Until a thing beloved becomes a thing parodied, it has not completed its life cycle. Such is love’s work in this fragmented and proliferated world. Recognising the parody before the love, when some hear the dialogue “Mere paas maa hai” (I have a mother), they might spot the meme before the movie. But, perhaps, the movie from which the meme has been pulled — Deewaar — still stands its hefty, uncontested ground, 50 years since its release in 1975, running to packed theatres during the Amitabh Bachchan retrospective in 2022.

Some movies can withstand their memes.

It does help that Deewaar gets referenced with sincerity, and not irony, as a film and not a template, time and again — here, in a scene in Loins of Punjab (2007), there in an interview with director Danny Boyle who calls Deewaar “absolutely key to Indian cinema”, and when music composer A.R. Rahman accepted his Oscar for Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire, he even quoted the film, “Mere paas maa hai”.

Also Read | Inside Papa’s Bombay: The Exclusive Dinner Party Celebrities Can’t Get Enough Of

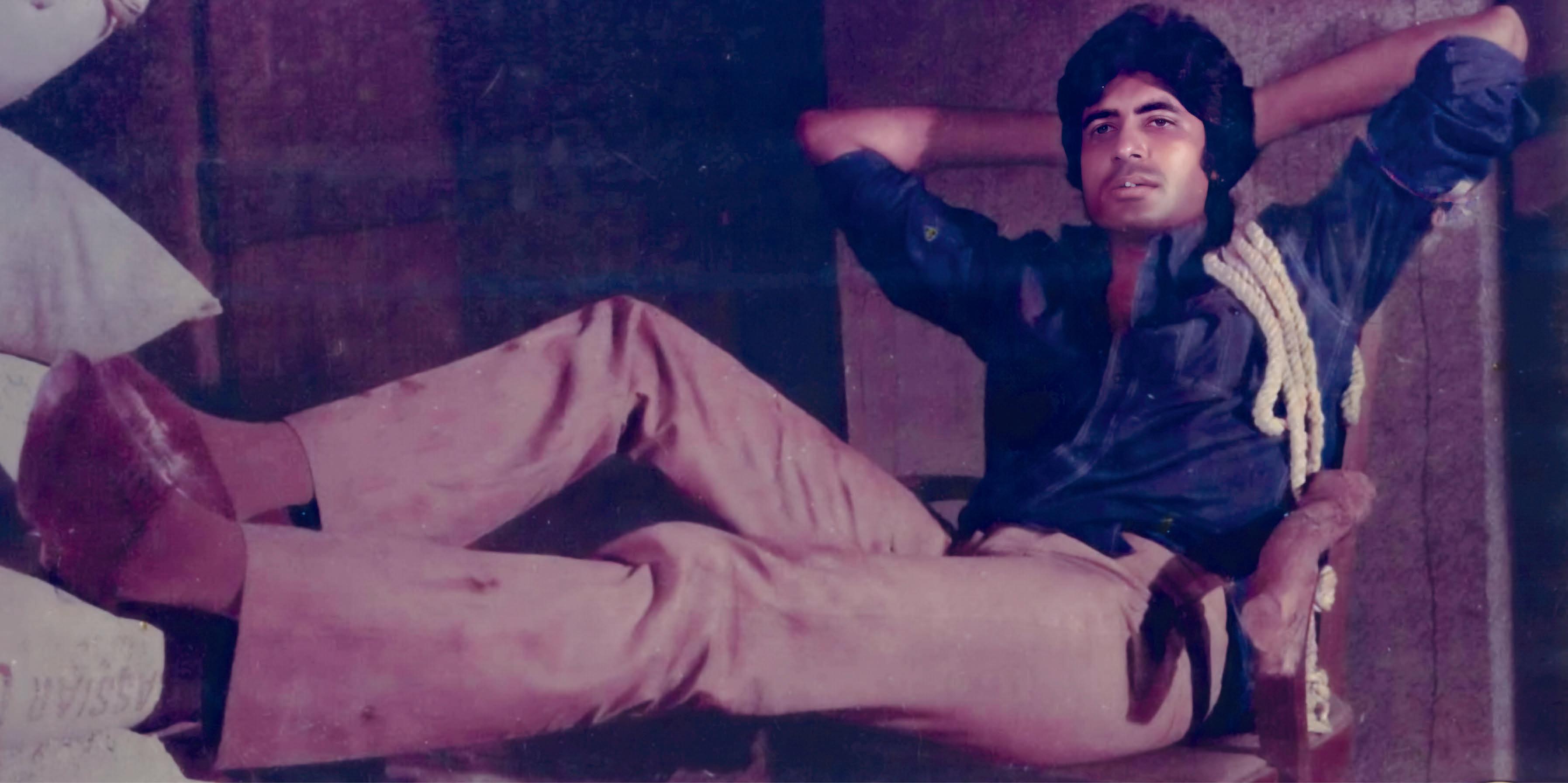

Directed by Yash Chopra, Deewaar trails two brothers who tread different paths — Vijay (Bachchan), becomes a dockworker, and later, a smuggler, while Ravi (Shashi Kapoor), becomes a police officer, trying to chase and put a cork on the very smuggling activities with which his brother paid their bills. A moral conundrum lifts the film out of its melodramatic gestures, its easy excess, teasing out the tension between respectability and heroism — that while Ravi is the respectable and honourable figure, allied to the nation, the Constitution, and that while it is him who mouths the famous dialogue, it is the disreputable Vijay who is, ultimately, the vanquished hero.

With a screenplay written over 18 days, in one draft, with dialogues being chiselled for another 20, the iconic screenwriter duo of Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar were reaching out into the past, influenced by films like Mother India (1957) and Ganga Jamuna (1961). But in other ways, they were also grasping at a more modern sensibility, something more universal, yoked to the temperature of the years being lived through, with economic productivity in steep decline, essential commodity prices being hiked, cities crippled by strikes — over 47 per cent of the organised labour force in 1974 may have been involved in some strike action or another — and protests that made possible the very idea of an undone state. A few months after Deewaar’s release, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency. Alongside this post-independent hope that congealed as smothered disenchantment, there was also urban alienation. For all his bravado, Vijay became the silhouette of the lonely hero with a doting mother that cast a long shadow on our cinema — a trope we see being celebrated in films and franchises as recent as Pushpa and KGF.

If you want to pursue some naughty psychoanalysis, you could chalk it up to Javed Akhtar’s awkward relationship with his father. In a conversation with Nasreen Munni Kabir, published in Talking Films: Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar (Oxford University Press, 1999), he notes, “In our country, we don’t have a strong tradition of bonding between father and son, anyway. There is an awkwardness even in so-called normal households.” Vinay Lal, in his book Deewaar: The Footpath, The City and the Angry Young Man, sees the missing father as a cultural trope in Hinduism that can be traced back to the Ramayana and Mahabharata, where fathers are either missing or whose virility is suspect. Whatever the reason, the consequence, as Kabir notes in the conversation, is a trend of “reducing the screen family to a single character — that of the mother”.

Also Read | Sharan Venugopal on 'Narayaneente Moonnaanmakkal' and Bringing Personal Memories to Life

While the titular deewaar, or wall, is the one between brothers, between good and evil, as Akhtar notes, it also, more poignantly, represents “Vijay’s relationship with the Parveen Babi character in Deewaar, or his relationship with the Raakhee character in Trishul (1973) — it is very difficult for him to tell these women that he loves them. It is equally difficult for him to express his love for his brother or his mother. There is a storm raging within him, so he has closed the doors. That is how such characters feel safe. They create a deewaar between themselves and their emotions.”

The heroic man, tongue-tied in front of his lover, wrecking the world to produce some form of order — is that not a familiar arc? As Akhtar mentions, “I remember in Delhi or in Bombay or in Calcutta, many respectable people would boast of their great friendship with various smugglers. So, in a society in which such things are acceptable, it was no wonder that such a hero was acceptable too.” A broken hero for a broken world.

With Deewaar, Salim-Javed also flushed a new modernity into cinema. It is not just cigarette smoking, which is usually assigned to the vamp or the seductress. Here, all three — Babi’s, Kapoor’s, Bachchan’s — characters smoke, as scenes linger in tenderness, no connotation from the ash spilling over into the moral overtones of the moment. The language, the setting, and Akhtar insists, even the accent, language, and tempo exuded a modernity, even as it let the women fester away from the limelight. “It wasn’t only because the characters in the film wear trousers and jackets…. It was much more urban, much more contemporary, and the kind of moral dilemmas that it posed were very much of its own era…. In Ganga Jamuna (1961), whatever was happening, was happening to Ganga. In Deewaar what was happening to Vijay was happening to many of us. Maybe we did not react like Vijay, but we could identify with him more than we could with Ganga.”

Salim-Javed together created the language of this alienated, anti-establishment, suave heroism in Hindi cinema in the 1970s, given shape and voice through Amitabh Bachchan, in films like Prakash Mehra’s Zanjeer (1973), Chopra’s Deewaar, and Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (1975). And while Sholay exploded past itself, turning into a fortified myth, Deewaar still has space to negotiate with its shortcomings, its exuberances, and fresh appeal.

Interestingly, the producer, Gulshan Rai, wanted to cast Rajesh Khanna — who was, at the time, coasting along on his late 1960s superstardom, and considered more of a hero than Bachchan — for the role of Vijay. But Yash Chopra, who had seen Bachchan in Zanjeer, insisted till he got his way. With Shashi Kapoor’s character, too, there was some coaxing needed, given that Kapoor is elder to Bachchan but would be playing his younger sibling. Salim-Javed, who held some sway over the casting process, convinced both Kapoor and Gulshan Rai.

Between the Vijay of Zanjeer, a police officer, and the Vijay of Deewaar, a smuggler, was a gap of not just two years, but two directors as well. As Bachchan notes, “Prakash Mehra presents his subject differently. He likes to tell a story, not to disturb the frame, doesn’t use too many edits, and doesn’t play around. He barely uses the trolley, and very rarely the zoom. Yashji always zooms, for every shot, close-up, sequence, and song. Movement means a lot to him.” It was this aesthetic of quick cuts and lubricated motion that gave Deewaar its force and flash. Chopra does not even let the scene linger after that famous dialogue. It is an immediate shove to the next scene.

While Deewaar is a story of disillusionment, it is not a story of revenge — and this is something Salim-Javed were careful about. In fact, Deewaar is not even violent; it has fewer action scenes than, say, Bobby (1973). Vijay is not in search of the industrialist who duped his father. Neither is he after the construction manager who shoved his mother around. His anger is more systemic. His solution is less calibrated by reason.

Also Read | Namit Malhotra: 'The Ramayana' Belongs to The World—No One Person or Entity Owns It

Despite having few songs, it is this solution in Deewaar, this anger that is not ugly but festers nonetheless, that captured the imagination of not just the North Indian audience, running in theatres for over a hundred weeks, but filmmakers across the world, from Iran to Turkey. A few years after its release, in 1979, Deewaar was more or less faithfully remade in Hong Kong as The Brothers, which gave further impetus to John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow (1986), though in Woo’s reimagining, the warring brothers reconciled as the film claps shut.

In India, apart from the remakes — Magaadu (1976) in Telugu, Thee (1981) in Tamil, Nathi Muthal Nathi Vare (1983) in Malayalam — it was the romance with the number 786 that lingered. It is a holy number in Islam, which, according to Arabic numerology, is the total value of the letters “Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim” (In the name of Allah, the compassionate, the merciful). In Deewaar, it is Vijay’s billa number — his badge number — when he worked at the docks. Vijay’s much older Muslim co-worker Rahim Chacha (Yunus Parvez) tells him, “Jaise hota hai na, Om? Vaise hi saat-sau-chiyasi…badi barqat hai isme. Is bille ko humesha apne paas rakhna.” (Just like there is Om for Hindus, there is 786 for us Muslims. There are a lot of blessings in this number. Always keep this badge near you.)

Throughout the film, Vijay is saved by the badge that he lodges in his pocket, his heart’s own bulletproof vest. In the end, when he drops the badge and is unable to retrieve it, his death becomes inevitable. Such are the ways masala cinema trains us, prods us to enjoy it by rendering its edges predictable. Here, it is impossible to shrug off the inflection of real-life smuggler Haji Mastan’s biography on Deewaar, given he migrated to Mumbai in the mid-1950s and, having worked at the docks — where he, like Vijay, had a lucky number — made a fortune for himself in the 1960s and 1970s.

This number 786 and its myth would cascade through the films of both Bachchan and Chopra. In Manmohan Desai’s Coolie (1983), Bachchan plays a coolie with the same billa number — it even makes an appearance in the ‘O’ of ‘Coolie’ on the poster. It was during the shoot of this film that Bachchan met with a near-fatal accident, where he was rendered clinically dead for a few minutes. But he recovered. Why would the masses not believe that it was the badge, number 786, that protected him, a blessing that slipped from reel to real?

The number also makes an appearance in Thee (1981), a scene-by-scene remake of Deewaar in Tamil, starring Rajinikanth in the lead role. It is also the prisoner number of Veer Pratap Singh (Shah Rukh Khan) in Yash Chopra’s Veer-Zaara (2004) — “bismillah ka number” that becomes his identity until a lawyer (Rani Mukerji) comes to fight for his justice, his love, wondering if he is a “khuda ka banda”, a man of god. It is a number that gets sprinkled around — here it is in the registration number of Ajay Devgn’s car in Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai (2010); there it is in the title of Akshay Kumar’s Khiladi 786 (2012).

It is true, as Akhtar feels, that Deewaar cannot be remade today, “I don’t know if I could find that kind of intensity and anger, that thrust which made us write Deewaar…. [The film’s] dilemmas are no longer such big problems.” But even as the anger might have dimmed into irony and intensity mistaken for excess, Deewaar’s broad arc stands as a yardstick for its time, and its granular details keep shedding its presence as the decades move and the trends turn.

To read more exclusive stories from The Hollywood Reporter India's February 2025 print issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest book store or newspaper stand.

To buy the digital issue of the magazine, please click here.