Suggested Topics :

A Guide To Raj Kapoor’s Cinema On His 100th Birth Anniversary

However you choose to read it, what is indisputable is that his films provided other mainstream filmmakers a template with which to imagine their worlds

There is the myth woven around Raj Kapoor’s cinema and then, there is Raj Kapoor’s cinema. Speak to people about his oeuvre, and you might often hear more about how his films were received — his popularity in the Soviet Union, where 64 million people bought tickets to Awara (1951), for example — or how his films can be read — as symbolic of some post-independent Nehruvian spirit, for example, melding? Congealing has a negative connotation Chaplin with romantic socialism that was sexualised later on. The adulation is thick. It is hard to see the film through the haze of paratext. This is the problem with cinema that is received pre-engaged, bolus chewed on.

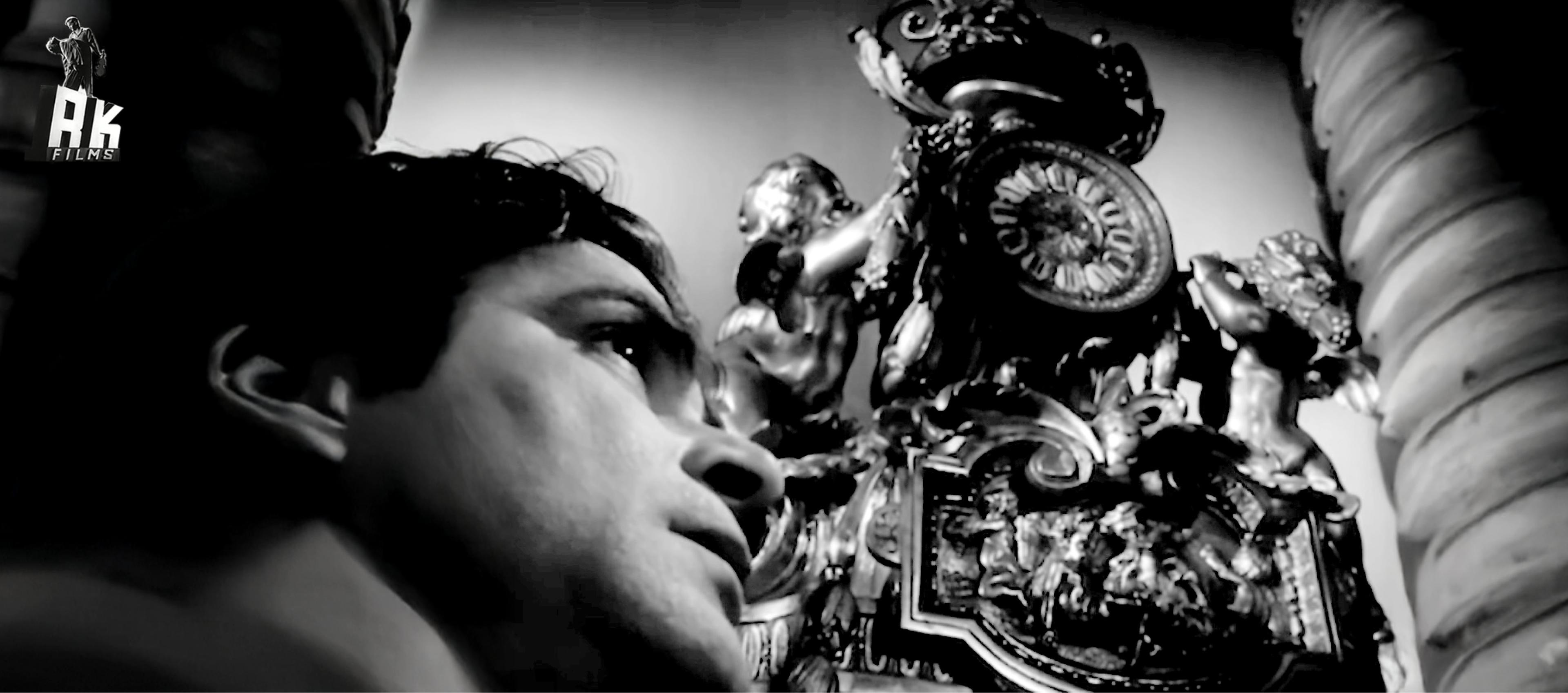

As a director, Kapoor’s filmography spans decades, from Aag in 1948 to Ram Teri Ganga Maili in 1985, as India tumbled from post-independent state-heavy socialism into the early hints of bootstrapped liberalisation, through three wars and an Emergency, and most perceptibly, from black and white to colour — what shadows were to the former, flowers would become to the latter. Alongside him, almost throughout, were his comrades in cinema: cinematographer Radhu Karmakar, sound designer Allauddin Khan, and art director M.R. Achrekar.

Kapoor’s father, Prithviraj Kapoor, was a prominent actor, onstage and onscreen; Kapoor’s first stage role was at the age of five for his father’s production, and he spent his childhood assisting his father between the Imperial Studios in then-Bombay and New Theatres in then-Calcutta. Prithviraj Kapoor was a founding member of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), linked to the Communist Party of India (CPI) and connected to the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA). Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, a screenwriter for a number of Kapoor’s films, and a close collaborator, was also a member of the PWA. These were artists in search of new political horizons. Cinema was a mere medium, a tool in that pursuit. But Kapoor differed slightly; he wanted to be the showman.

In 1948, Kapoor made his directorial debut with Aag, in which he starred alongside Kamini Kaushal, Nigar Sultana, and Nargis — three of the leading actresses of that time. A strangely balanced film, it unfolds when a childhood dream of performing with a friend goes unfulfilled — a dream the protagonist, Kewal, keeps trying to materialise later on in his life as he tumbles into love three times over. Kewal keeps trying to replicate lapsed innocence. These are characters who are animated by ideas, people becoming vessels carrying certain notions; there is no interest in or curiosity for psychological realism, or a fuller realisation of character. It allows grander narratives to be spooled. Kewal is pursuing inner beauty. He falls in love with a nameless woman who has arrived from “narak” or hell — one of the first few references in Hindustani cinema to Partition. To test the length of the shadow that inner beauty casts, Kewal burns himself, scarring his face, hoping his lover will still be by his side. She leaves him.

This pull of desire away from a scorched face gets retraced three decades later, in Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram (1978), and this tripartite invocation of women two decades later, in Mera Naam Joker (1970).

It is his relationship with Nargis — as an actor, but also, lover — that gets memorialised in the RK Films logo, a pose from Barsaat (1949), in which Kapoor, the poetic urban slick, is holding a violin and Nargis, who plays the smitten daughter of a Kashmiri boatman, is swooning backwards.

The urban-countryside, rich-poor dichotomy that Kapoor would not tire of was fermenting here, as was his enduring relationship with Nargis, who would act in Kapoor’s following films, Awara (1951) and Shree 420 (1955). They would make seventeen films together.

Though Nargis debuted with Mehboob Khan, Kapoor forbade her to act in his films. Her return to Khan’s filmography with Mother India (1957) was also, then, her exit from Kapoor’s filmography, even as every RK Films production began with her silhouette. Some absences are too present.

In Kapoor’s films, to be rich is to be morally compromised. As someone born into riches, if you can emerge as moral, it is only through love. As Nasreen Munni Kabir notes, his films offer a Marxist analysis, without a Marxist solution — the solution is only, always love. That is how you endure wealth — which could be gotten from urban preoccupations like a lawyer in Awara, a businessman in Shree 420, a politician in Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985) or rural yawns like a land-owning thakur in Prem Rog (1982).

There is a strange tension in his films — where on the one hand, he is intent on colouring the rich as inherently evil, close-minded, even parochial, but at the same time, his films luxuriate in these spaces. They prefer the bungalow to the shack. While Kapoor plays the tramp-like smudged poor in both Awara and Shree 420 — “Indian Charlie Chaplin” is another phrase thrown at Raj Kapoor’s early filmography — the poverty is only celebrated as a communal event — ‘Ramaiya Vastavaiya’ in Shree 420 or ‘Na Mangu Sona Chandi’ in Bobby. There is an isolation that comes with wealth, a community that accompanies being poor. The rich father is often absent or abusive. The rich parties that characters attend reluctantly glitter, as though the surface is scrubbed with jewels. This is where ambivalence enters his filmic language, which is not political in any explicit, call-to-arms sense.

The dissolve edit and the dramatic scene blocking — in which characters move between the foreground and background as distinct, distant spaces — douse his earlier films. Sangam (1964) is the apogee of this. The film, a love triangle between three childhood friends (Raj Kapoor, Rajendra Kumar, Vyjayanthimala) across class, takes Raj Kapoor’s idea of love idealised, his preoccupation with this love across boundaries of class and etiquette, all while playing with a new form — he served as editor for the first time, and also shot not just in colour, but in Europe, a first for any Indian film. A masterclass in staging, characters pushing and pulling from the foreground, the climax plays out like a triangulating dance between the three characters and a gun that keeps changing hands, until the trigger is pulled.

In the film he makes a curious, cinematic division between love that is a “majboori”, an intuitive compulsion, and love that is “dharm”, or a duty that must be nurtured and performed. Vyjayanthimala’s character, Radha, experiences both, one per man.

While performing well in Europe and across the Soviet Union, this film, like most of Kapoor’s films, was unable to scratch at the American market. The demands they make on their movies seemed incompatible with Kapoor’s imagination — which he sublimated as the Indian imagination. In an interview Kapoor notes, “I showed it to some American distributors … but they wouldn’t buy it, because it was about a woman who married one man while she was in love with his friend. Why did she marry him in the first place, if she wasn’t in love with him, they asked. Why didn’t she divorce him and go to the one she loved. I ask you, would such questions bother Indians?”

It is with Mera Naam Joker (1970) — at 248 minutes, one of Indian cinema’s lengthiest films, shown with two intervals — that Kapoor struck upon his film maudit, a commercial failure that pulled him into deep financial crises. Considered both “compulsively watchable” and an “astonishing train wreck of a film," Mera Naam Joker felt like a worrying pivot in Kapoor’s filmography.

Mera Naam Joker onwards, with Bobby (1973), Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978), Prem Rog (1982) — what Kapoor saw as his “return to purposeful films” — and finally, Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985), there is something uncomfortable about Kapoor’s depiction of eros, because it is inscribed entirely on the exposed body and cleavage of his female actresses. In Mera Naam Joker, Simi Garewal plays a teacher — Christian, of course — who becomes the object of the teenage boy’s lust. We see her bathe. Kapoor was extremely perceptive to the demands of his audience, but sometimes, it could feel like he was shooting from the shoulders of his spectators, to luxuriate in his lust.

While showing writer Khushwant Singh the rushes of Satyam Shivam Sundaram, of Zeenat Aman’s covered face, exposed breasts, Kapoor whispered to Singh, “I love little girls with large bosoms… I suckled my mummy’s bosom till I was 5, played with it … I am a bosom man.” The men, often, wither away as objects of lust, especially as Kapoor stopped acting in his own films, populating it with his stiff sons. Pursuing lust is not, in and of itself, worrying, but the easy eros on screen felt like it was coming at the cost of, compensating for something else — the eros that characters feel for each other. That seems to have been replaced by the salivating audience and the screen.

When Dimple Kapadia, making her debut in Bobby, enters the scene in her orange cola bikini, the camera leers at her waist. Compare this to Nargis wearing a swimsuit in Awara — shot indoors in a set that was constructed because Nargis refused to be outdoors in a swimsuit — where, as Rachel Dwyer notes, “the close up [is] of her face with her hair blowing in the wind, not one of her body”. A voyeurism had entered Kapoor’s film language as he furnished his cinema with newer, younger actresses. What is also true is that none of Kapoor’s freshly minted heroines could muster, what Michael Newton calls Nargis’s “spontaneity of feeling” — this stilted, staged presence begins to permeate his films. Sangam, arguably, is the last great Raj Kapoor film.

In his earlier films, the dichotomy between the vamp-like glamorous woman and the demure, cultured one was clear — Ruby (Cuckoo) the dancer against Neela (Nimmi), the swooning hill girl in Barsaat, Maya (meaning illusion, played by Nadira) the dancer against Vidya (meaning knowledge, played by Nargis) the schoolteacher in Shree 420. If he had to show his heroine, the moral and romantic centre of the story as sexualised, he had to forgo the vice-virtue binary that people attach to skimpy clothing. The white diaphanous sari that Nargis wore to court in Awara and Vyjanthimala wore across Europe in Sangam would become the only thing Mandakini and Zeenat Aman would wind round their bodies as they bathed under waterfalls.

However you choose to read Raj Kapoor’s cinema, what is indisputable is that his films provided a template for other mainstream filmmakers to imagine their worlds — whether Yash Chopra, or later, Sanjay Leela Bhansali — as not built on the psychology of character, and the demand for realism, but with characters whose only preoccupation is love. As Kapoor spoke of his audience, “We sell them dreams; they buy them.” And it is true that over the four decades of his filmmaking, we bought some, many, in fact, and with others, we are still turning the dreams over in our hands, wondering if the purchase is worth the price.