Suggested Topics :

An Essential Shyam Benegal Guide: Charting The Auteur’s Legacy With Five of His Best Films

How do we tell the story of the Indian Parallel Cinema movement? The answer, of course, is through Benegal’s cinema—an unwieldy body of work that provides no easy answers, only succulent clues that keeps one searching.

Wobbling on his walking stick, 88-year-old Shyam Benegal showed up in a cream half-sleeve shirt, pants, and chappals to the Mumbai premiere of his latest, most expensive, and his last film, Mujib: The Making Of A Nation (2023). His shirt pocket sagged under the weight of some folded papers and his phone, which were cupped in it. He had no patience for fanfare, even as the moment demanded it.

Read More | Shyam Benegal Passes Away At The Age Of 90

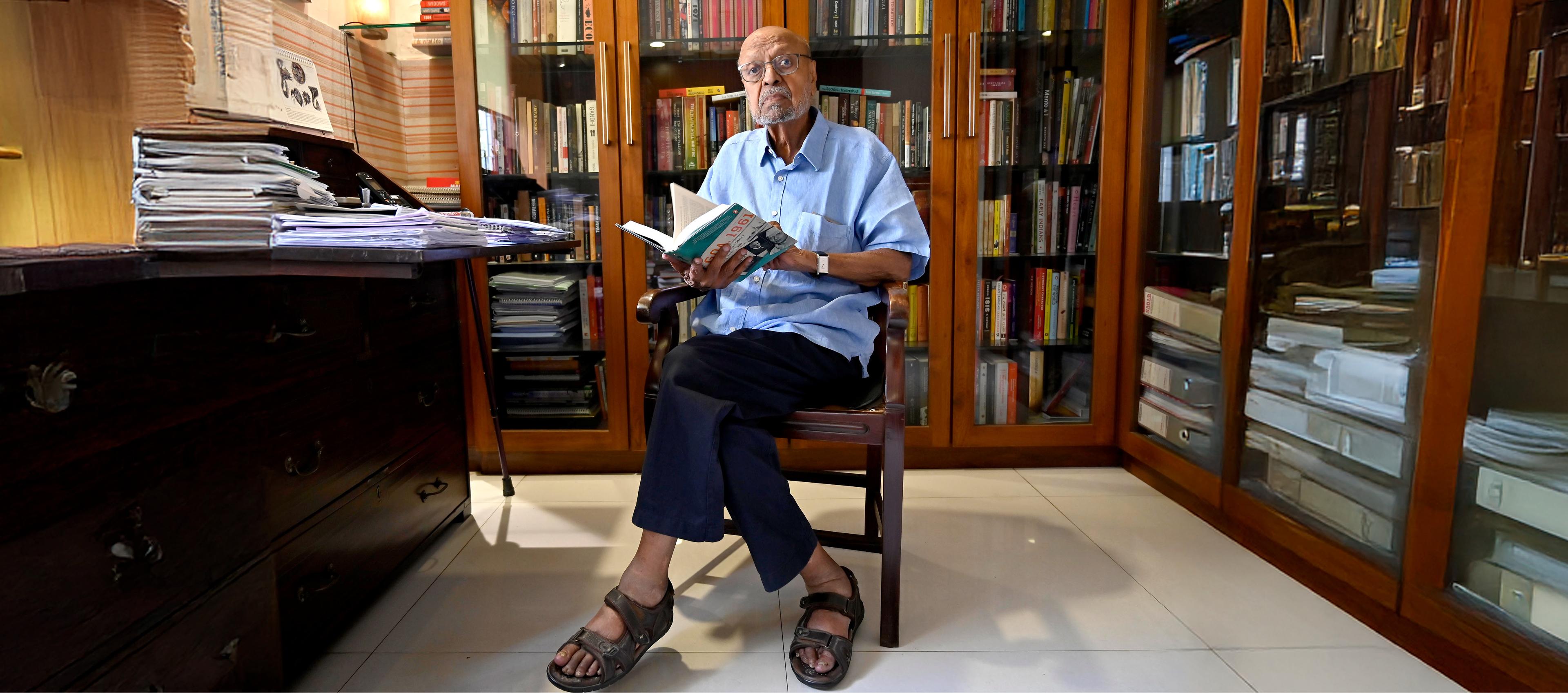

There was something old school about Benegal. His office, his refuge against domesticity and retirement, is in South Mumbai. Even as Hindi cinema moved further North, turning South Mumbai a relic, Benegal stayed put.

He went to work every day, except Sundays. He did not use the computer; his secretary printed out his emails for him. A rosewood desk that was bought from Chor Bazaar was his workspace, on which decades were spent writing and tinkering with the scripts that would make what we today call parallel cinema. This was a film movement with rooted perspective, and a desire for spatial, historic, and linguistic authenticity. Despite being singed, his films embodied patient cinema, with uncertain and unstable psychologies expressed as gazes and glances that mean too much in the head, and too little on the lips.

With a pursuit for realism, he brought out a fresh crop of actors: Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Girish Karnad, Amrish Puri, Anant Nag—all staggering into his filmography from the Film And Television Institute Of India, Pune (FTII) or the National School Of Drama, Delhi (NSD) with their brash, unkempt beauty, and a fire for this fickle thing called justice.

His early films, from the 1970s, were full of rage against the system—caste, class, gender. His debut Ankur (1974) was made at a time torn between the fading star of Rajesh Khanna and the up and coming vigilante disillusionment of the Angry Young Man. A third path was being forged.

His first decade as a director was a miracle. There was the anger of his ‘rural uprising trilogy’ of films, Ankur (1974), Nishant (1975), and Manthan (1976)—the last crowdfunded by farmers in Gujarat. This was followed by the biographical Bhumika (1977), whose full feminist rage gets expressed in the brothel-drama Mandi (1983).

Then, there was the bilingual Kondura (1978), Benegal’s interpretation of Ruskin Bond’s novel in Junoon (1979) and the Mahabharata in Kalyug (1981), and the dainty fugue of magic realism in Trikal (1985).

As Benegal’s films grew in scope, budget, and glamour, people began throwing asperions at his cinema. After Junoon (1979), with Shashi Kapoor, for example, India Today wondered “whether Benegal has succumbed to the siren calls of commercialism”.

Benegal, nonetheless, trod on.

Alongside this, he was also making documentaries, while also pursuing positions that would keep him in close company with the State. He served as the director of the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) from 1980 to 1986, and as the chairman of FTII twice, from 1980–83 and 1989–92. He would spend this decade working with Doordarshan, giving cinematic shape to Nehru’s Discovery of India in Bharat Ek Khoj (1988), among other shows.

Read More | The 10 Best Hindi Performances of 2024, Ranked

Post the demolition of Babri Masjid in 1992, his trilogy of films—Mammo (1994), Sardari Begum (1996), and Zubeidaa (2001)—foregrounded Muslim women in all their grating adamance and barbed pathos. In this context, his swerve to comedy in Welcome To Sajjanpur (2008) and Well Done Abba (2009) was considered acts of foaming froth, of blunted politics with a neoliberal sheen, but located in these quiet comedies are the broken aspirations of a disenchanted people, which nonetheless does not leave them hopeless.

Benegal’s cinema was never cynical, even when it was tragic, especially when it was comic.

With Mujib, a starched, marathon run-through of the life of the late Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, considered the father of Bangladesh, Benegal was returning to the genre that kept snagging at him through the decades: the political biography.

In the 1980s it was Nehru (1984), in the 1990s it was The Making of the Mahatma (1996), and in the 2000s, it was Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero (2004). He loved to tell the story of nations yoked to the story of its foundational figures. The question, then, becomes, how do we tell the story of the Indian Parallel Cinema movement? The answer, of course, is through Benegal’s cinema—an unwieldy body of work that provides no easy answers, only succulent clues that keep one searching.

In his last interview, with Samdish, Benegal said without emphasis or flourish, “I don’t feel like I could have done very much more than what I did. I wanted to become a filmmaker. I became one.”

The following five films, then, provide a pathway into this vast oeuvre, films that establish his wide embrace as much as his serrated gaze, his capacity for the outsized and the intimate, the commercial and the caustic.

Nishant (1975)

From Benegal’s ‘rural uprising trilogy’, Nishant is the most crowded, cinematic, and elusive. While Ankur’s finale is easier to digest, the final rural rebellion at the end of Nishant, against the rapacious and extractive landlords, is so angry and directionless, it flips the very purpose for which it was lit aflame.

To sit with Nishant is to sit alongside the bare-chested, sculpted, and vice-ridden sex appeal of the late Amrish Puri’s character, the feudal landlord; the pencil moustache of Naseeruddin Shah’s character, the landlord’s brother, whose lost person flits between kidnapper and kin; Shabana Azmi playing both the kidnapped, sexually assaulted wife, and the coveted concubine, sublimating her revenge as Stockholm syndrome over the course of the film, discovering her sexuality, leaving her husband, the principled teacher played by Girish Karnad high, dry, and cuckolded—a character that Benegal in interviews calls a “wimp”.

This was Benegal’s rejection of the middle-class intellectual figure.

Despite Indira Gandhi’s love for Ankur and Benegal’s close association with the State, Nishant was stuck as part of the censorship regime of the Emergency. Benegal wrote to Indira Gandhi, who saw the film and insisted the censorship be lifted. Only some demands were made, though. Benegal was told to remove markers of time and place, to make it clear that all this rage and rebellion was happening in pre-Independent India.

Benegal relented, though it did not matter. Those who knew, knew.

Mandi (1983)

From a thimble-thin story by the Urdu short story writer Ghulam Abbas, inspired by the story of Nehru — who in 1929 was the chairman of the municipal board of Allahabad, deciding to move the brothel from the center of the city, near where he was born and lived — the ensemble Mandi emerges in all its raucous colours, screeching arguments, and floating, abstract apparitions.

Set, for the most part in a brothel, the film is a bursting belly, and this heavy sense of something important and nondescript ripping past in all the crossed wires is pressed up against the film’s surface.

It was around this time that Benegal could feel a shift underfoot in the way he was relating to and expressing stories. “I became interested in simultaneity … or what one might call the subjective-objective, simultaneous renderings of the past and the present. All these things enabled me to expand the scope of the narrative and to take on narratives which otherwise might seem unfilmable.”

Nehru (1984)

Co-directed with Yuri Aldokhin, and produced by Films Division of India in collaboration with Center-Nauch-Film Studios, and Sovin Films, Russia—an indication of the Russian affection for Nehru, one which he returned—the film charts his influences, heartbreak, and longing, stuck somewhere between Buddha, Lenin, Marx, and Gandhi. Benegal called this a ‘first-person' biography as opposed to an autobiography.

Narrated by Saeed Jaffrey, one of the most curious effects of the film is how Nehru emerges as a character from the shards of letters, reminisces, and diary jottings—and not as a mythical figure, but a fragmented but strident man yearning for myth, with life and its whips coming in his way.

You can see both the posture and the person as separate, but connected silhouettes.

Zubeidaa (2001)

The "Khalid Mohamed" trilogy—Mammo, Sardari Begum, and Zubeidaa—came out of Benegal’s fixation with the life of Mohamed, an Indian film critic. Mohamed was invited to script the three films—Mammo being the story of his grandmother’s sister, Sardari Begum about a distant aunt, and Zubeidaa chronicling his mother’s life and death, her marriage into crippling royalty, playing second wife, and ultimately, bringing death to herself and her husband.

In many ways, Zubeidaa was Benegal’s most mainstream film, with AR Rahman scoring the film in the only way he knows—melodically, claustrophobically—and Karisma Kapoor bestowing it with commercial glamour. While speaking to William van der Heide, Benegal remembered Zubeidaa being “held up as an example of the direction in which popular cinema should move”.

Welcome To Sajjanpur (2008)

From a filmography bursting at the seams, with over 24 films, most of which pushed Indian cinema into a more conscientious orbit, the choice of this air-woven comedy might seem strange.

But populated with oddballs like a trans woman who wants to enter politics, a superstitious mother who wants to get her daughter married to a dog to evade her horoscope’s ill fate, a daughter who rides her scooter out of every scene, a widow in love, a housewife longing for her husband who has moved to the city—all of these characters tethered to a letter writer in a fictitious village, Welcome To Sajjanpur is a bumbling film, light on its feet, warm in its heart, and charmed in every step.

Above all, it is testament to Benegal being a filmmaker who had no disdain for the commercial, the popular. Pradip Krishen, in fact, describes him as “the first Parallel Cinema wallah to break through to a popular audience”, a breakthrough that was possible entirely because of his “apparent readiness to compromise … separat[ing] his praxis from the more radical aesthetic and political approaches of such committed Marxist filmmakers as Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, and Mani Kaul.”

Even if his politics were not committed, politics were always present in his films. As he told van der Heide, “To me the overall experience of living is very important and the overall experience of living in my country always includes politics.”