Suggested Topics :

Hair and Torture in 'Dhurandhar': Decoding the Prosthetics and Character Designing in Ranveer Singh's Spy-Thriller

Preetisheel Singh, the character and prosthetic designer in 'Dhurandhar,' talks about elevating prosthetics to an art form in Ranveer Singh's recent hit

The first thing Preetisheel Singh clarifies is that she prefers calling her work “character designing” instead of merely “prosthetics”, for it is a combination of hair, makeup, and prosthetics that is done in her “lab” in Versova.

Singh begins working on a film by sitting with the script and director, charting the characters and their graphs—across both the wide sweep of time and the smaller durations, as wounds fester on their body and scars deepen. She, then, makes digital designs, which are shown to the director before bringing the actors in. Live casts—3-D scans—of the actors are then made, for her team to begin working on. This relieves actors from not having to sit for all the trials—it can be done on these casts.

Over the past decade and a half, Singh has worked in films like Haider (2014), Bajirao Mastani (2015), Padmaavat (2018), Kalki 2898 AD (2024), Chhava (2025), and the recently-released Dhurandhar, elevating prosthetics to an art form. From small detailing like ageing wounds and sculpting scars, to larger questions around a character’s hair and hairlessness, she co-created the characters that stain public memory. In Aditya Dhar’s Dhurandhar, her official credit is “Character and Prosthetic Designer”.

Despite its importance in the storytelling process and outcome, Singh notes, prosthetics is not considered worthy of an awards category, “Except for the National Awards, it is barely acknowledged.” Prosthetics is still considered a slapdash thing, “only meant to turn people into an old or fat person. It is high time we—and I include the casting director in this—get the recognition that is due.”

In this conversation, edited for length and clarity, she speaks of the various conversations that went into making the characters:

We should begin by speaking of Ranveer Singh’s hair.

Cracking the hair was important, we had to strike the balance between making it cinematic but not distracting because he is not a front and center character in the first part.

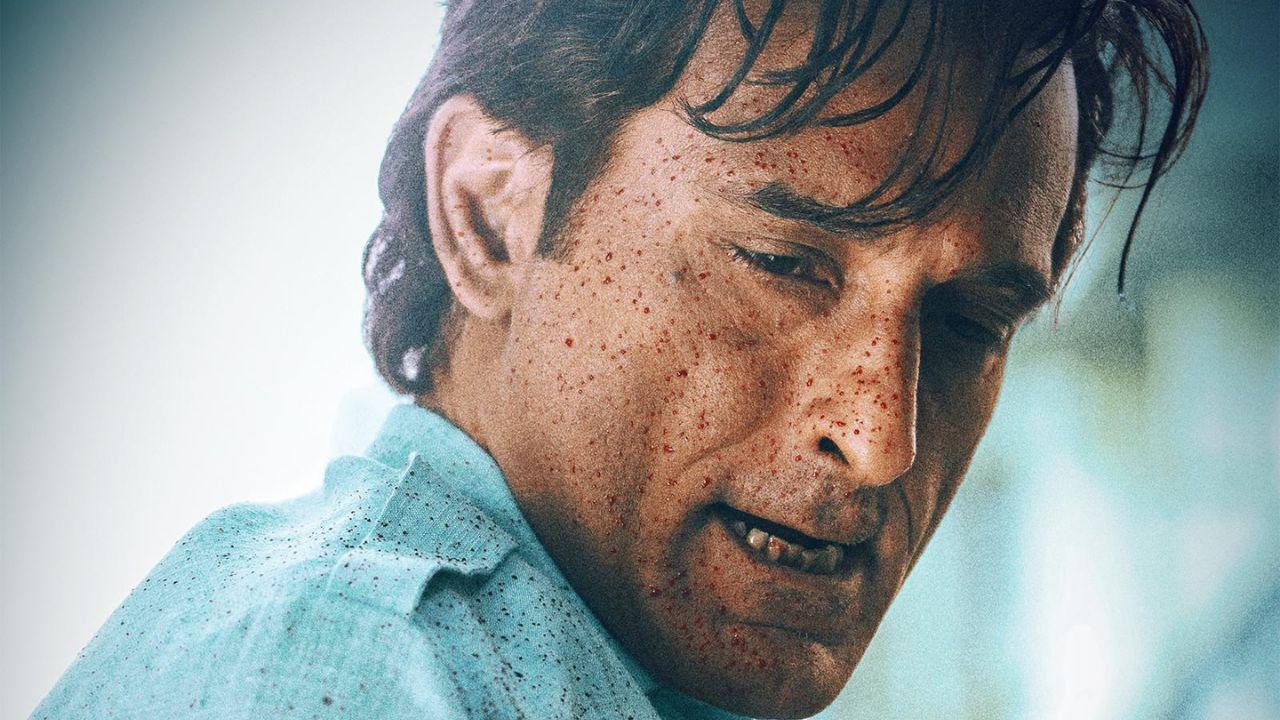

Dhurandhar expands over a certain time period, and I wanted to track that journey from getting into the “spy look” , where he doesn’t have access to money, doesn’t even have a house to stay in, being on the streets, to entering the gang. I wanted to show the initial rugged rawness, where he is not grooming himself every day, with unkempt grungy hair, tied into a ponytail sometimes. You see that greasiness in the texture coming across. Texture is very important to me. I even gave him freckles on his face, and tanned his skin tone. This builds character.

Everyone was initially apprehensive that he had long hair and brown eyes like Khilji, [his character in Padmaavat] and we didn’t want him to repeat that look. I told them not to worry, because I also did his Khilji look, so why would I repeat myself?

How long would it take to get Singh into this look?

Roughly, it would take 1.5 hours to prepare. If there was bloodwork, with scars and bruising, maybe two hours. But time was always of essence.

Over the years, in the film, his character grows his beard, and does not cut his hair, so I used a lot of extensions and wigs—for both beard and hair—because we were going back and forth between the looks while shooting.

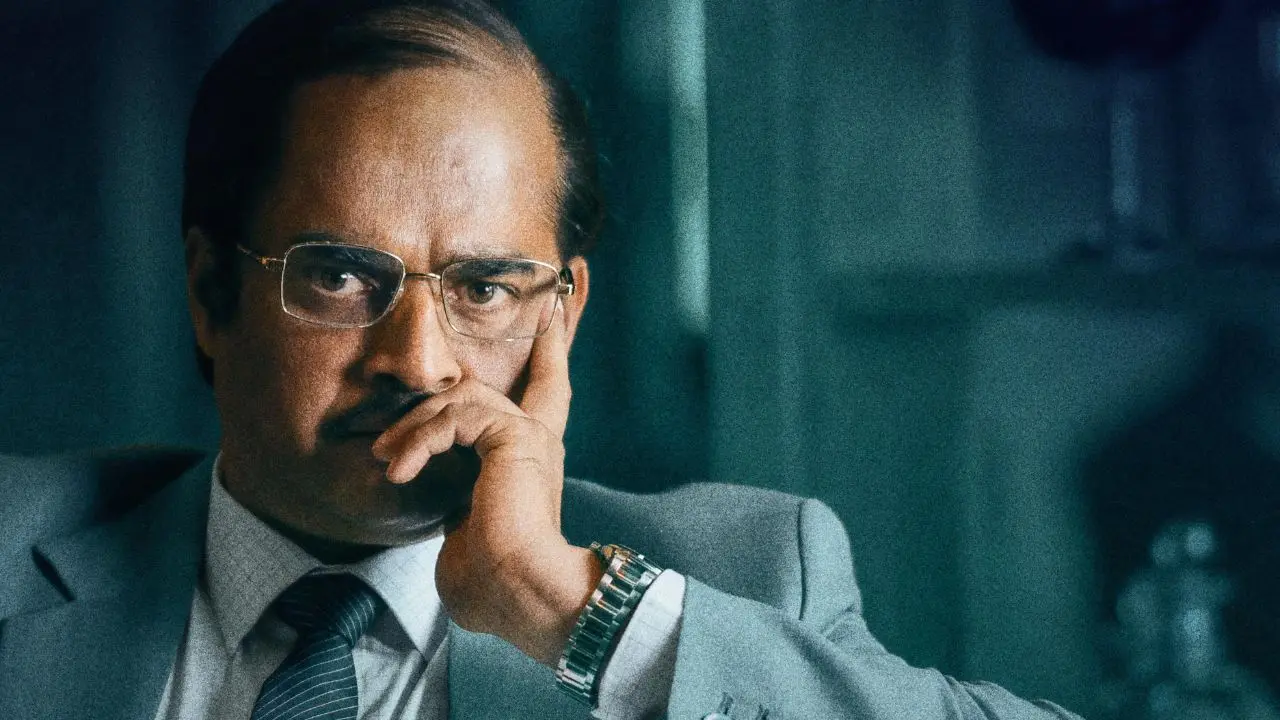

Akshaye Khanna’s character, and hair, particularly, has made quite an impression online. What were the kinds of conversations around his hairpiece?

I did his look in Chhava as well, turning him into Aurangzeb. Of course, he has a lot of experience working with wigs. I wanted to refrain from how he has already been shown and wanted his charisma to come across. There is a suaveness in his character, where his mere presence commands attention. He doesn’t need to say much. I gave him soft waves, and we showed the receding hairline. It is not a full head of hair. I remember doing the trial, he was looking at himself in the mirror, telling me he was reminded of his late father, Vinod Khanna.

What about Arjun Rampal’s character? At what point do you stop yourself from making such a handsome man look grotesque?

To make him look not attractive was difficult. I wanted his face to be layered under a lot of character streaks, and gave him a nice scar across his face. I wanted the menace and viciousness to come across. We did the gold plating for two teeth on top and the lower set as well. On the first day of shooting, he had asked if we could take another shot, with a closeup of his face, and he did this side smirk, and suddenly you realised, the teeth are what completed his character, Major Iqbal.

It is very important to me that even when they are not speaking, the character comes through strongly.

And Madhavan’s character? Was he always supposed to be lacking hair?

Yes, he was. I wanted his head structure to change. Madhavan has an elongated face. I wanted to make it round-ish. It is not very noticeable. You can see R Madhavan in the character, but a transformed version.

Talk to me about the prosthetics of torture—skin being pulled by hooks, brains being smashed, bodies by flung into iron nails. What are you using to make these scenes come alive, and how do we appreciate something you keep wanting us to look away from?

Haha, I suppose that is a job well done, then. Aditya was very clear that he wanted to show the brutality people go through and how actually, in gang wars, people torture each other in novel ways, to set an example as a warning. We would sit with Aditya and the action directors [Aejaz Gulab, Sea Young Oh, Yannick Ben, Ramazan Bulut] and would think of new ways we haven’t seen, of killing, of torturing. We would then sculpt those scenes.

Major Iqbal, for example, has hooked up a guy with fish hooks to extract information, and he is pulling the skin. So I made small folds of flesh and put the hooks in those pieces, so it gives the illusion of skin. I mostly work with silicon which has this lovely quality of imitating skin, when you colour it properly with good blood work. It is important for us to get the anatomy, the muscle structure right—nothing should give away that this is fake.

I know I have done this work and it is fake, but the execution was so good, that when we were shooting this scene, with the loud cries of the guy getting tortured, it made me cringe, and I walked off the set, because this brutality is a lot to take.

For the brain smashing sequence we deconstructed the body and brain parts—made from a mix of silicon and foam—to see what parts to smush off. We got an exact replica of the actor, so what you see is a dummy being smashed. The guy being flung into the iron nails is actually a person, though I made the iron nails out of foam, by coordinating with the production designer [Saini S Johray].

What was the most challenging look to crack or moment of violence to stage?

The challenge with Dhurandhar is that I had fifteen days to prep for this film. Besides, we shot a lot for this film. Usually a movie covers 80 to 90 locations. For Dhurandhar, we have covered 220 live locations.