Suggested Topics :

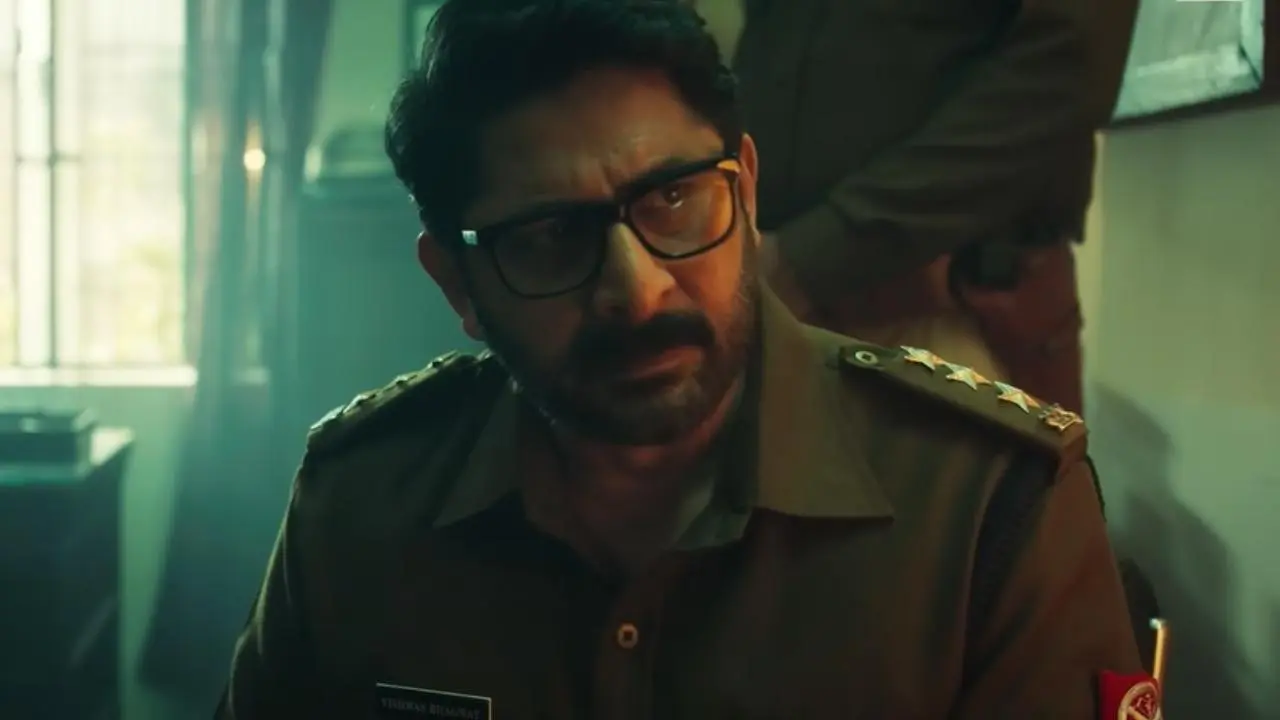

‘Bhagwat Chapter One: Raakshas’ Movie Review: Arshad Warsi Anchors An Overfamiliar but Potent Crime Thriller

Akshay Shere’s police procedural stays busy and sociopolitically alive to the India we live in today.

Bhagwat Chapter One: Raakshas

THE BOTTOM LINE

A well-crafted crime drama.

Release date:Thursday, October 16

Cast:Arshad Warsi, Jitendra Kumar, Ayesha Kaduskar, Tara Alisha Berry, Rashmi Rajput, Devas Dixit, Dadhi Pandey

Director:Akshay Shere

Screenwriter:Bhavini Bheda, Sumit Saxena

Bhagwat Chapter One: Raakshas starts like any Indian crime drama that wants the best of both worlds. The story is “inspired by true events,” but just about fictional and legally coy enough to stage itself as a franchise about a police officer who solves one case per film/season. It’s the Delhi Crime template. The ‘Chapter One’ in the title is a clue. As is the self-reverential opening slate: “To keep the truth alive, you must tell its story”. And a corny closing slate about courage that ends with an exclamation mark (!). In between these two quotes, however, Bhagwat defies its familiar status to stay humble, metrical and consistently watchable. Akshay Shere’s two-hour film has more in common with another well-crafted Hindi series. It shares its real-world source material with Dahaad (2023), the 8-episode thriller about a cop who gets drawn into a case of multiple missing girls and a potential serial killer. Like the show, the film does well to excavate the social fabric of a place that often serves as a portal between predator and prey.

The rural Rajasthan from Dahaad is small-town Uttar Pradesh in this film, specifically Robertsganj, a punishment posting for Crime Branch star Vishwas Bhagwat (Arshad Warsi) — the protagonist with mandatory anger issues, a happy family and a haunted past. In the weeks leading up to the Diwali of 2009, riots have broken out once the disappearance of a girl named Poonam Mishra becomes a political event; no-nonsense ACP Bhagwat gets right down to business. As an outsider, he has little baggage and no patience for the noise. He promises Poonam’s father that it’ll take him 15 days to find his daughter. But Bhagwat slowly realises that it’s way more complicated.

The Poonam Mishra case leads his team to discover a local prostitution racket and series of neglected FIRs and missing girls over the years, many of whom were already invisibilised by a system that parades its cracks as exotic designs. Parallely, we see a blossoming romance in Varanasi; charming youngster Sameer (Jitendra Kumar) woos a local girl named Meera (Ayesha Kaduskar). While Bhagwat struggles to wrap his head around the magnitude of the case, Sameer and Meera inch closer to eloping and consummating their love. For those who know the genre, this is clearly not a whodunnit; the suspense is that there’s no suspense. The two arcs are so tonally unrelated that they’re obviously related: it’s a matter of time before a sinisterly sweet Sameer’s life and a studious Bhagwat’s journey clash.

The setting of the film is important. The point of the story is that society is inherently antagonistic; all criminals have to do is thrive in its blind spots and broad-daylight shadows. Robertsganj here is a stand-in for a culture steeped in patriarchy, prejudice and bigotry. Bhagwat immediately encounters this when majoritarian political leaders allege kidnapping and “religious conversion” of their daughters; Bhagwat has to remind them that the suspect’s name is not ‘Abdul’ and that the demons invariably breed within. The constables and neighbours meanwhile waste no time in slut-shaming the missing girl who spent hours whispering into the phone on her balcony every night. The inference — even from her own family — is that she was morally flexible, and didn’t care for their reputation and honour. Everyone is one breath away from saying she deserved it; ditto for the sex workers and single mothers whose ‘nature’ is to be swayed by shady men.

The biggest draw of such narratives is not just the complicity of a system rigged against minorities, but also the nonchalance of those who’ve mastered the art of gaming this system. The perpetrator is almost a cultural commentator in disguise. As a teacher with a lay of the land, he knows exactly what buttons to push; the mind games are rooted in his understanding of an India that’s done half his job for him. He pretends to be a nice guy and lets the environment conspire to camouflage him — preying on the vulnerabilities of the marginalised, while milking the stigmas that arrive with interfaith love, premarital sex and female agency. At one point, he reminds a girlfriend of his (fake) Muslim surname; at another point, he rants about the lecherous male gaze to win her trust. Part of his plan involves dealing with a Muslim jeweller so that, when push comes to shove, he can use the man’s survival mechanism and fears against him. He’s twisted of course, but he’s so wired to perform and rationalise his ‘social service’ that Bhagwat’s challenge is to provoke the monster out of him.

The role of buses and bus stops in such stories cannot be overstated, especially after what transpired in Delhi three years after the events of this film. Misogyny is the kind of nonfiction multiverse that happens to us while we’re busy making superhero-sized plans. Dahaad was built around a Dalit female inspector who learns to embrace her identity because of the manhunt. As a feature-length drama, Bhagwat doesn’t have the long-form licence for character development, so it resorts to broader strokes. For instance, the inspector is given a tragic backstory; it’s hinted that he joined law enforcement after a similar spree affected his own childhood. It’s a bit of a cliche, particularly the needless flashback, but you can see why it’s written — to drive home a truth about how the worst criminals (and godmen) tend to use faith and tradition as a front to feed the perversions of their masculinity. Bhagwat’s ready-made pragmatism makes sense then; he’s not just ‘liberal’ by virtue of being a big-city cop.

Warsi expresses a sort of lived-in intrigue that nearly distinguishes ACP Bhagwat from his Asur persona. The comparisons are natural, but the actor stays grounded enough to exist in the slipstream of the plot’s rhythm. Thanks to his performance, the few hiccups — like the placeholder role of his family; the done-to-death subtext (the title alludes to chapters of the Bhagavad Gita); the excessive use of falcon and food analogies — don’t grate as much. It doesn’t matter that the mythological themes that are supposed to shape the film end up feeling like a postscript. Speaking of comparisons, who knew that ‘Jeetu Bhaiya’ was a great psychopath all along? Jitendra Kumar’s TVF fame has often worked against him in films and other mediums. Even when he plays someone else, it always looks like a version of the post-engineering and crabby middle-class underdog.

But perspective is a strange thing. In Bhagwat, he plays the same man to a chilling effect — it’s smart casting, but also a reminder that narrative context makes a huge difference in the way we perceive the limitations of popular artists (think Bobby Deol’s mute act in Animal). Kumar’s character more or less unfolds in the league of Vijay Varma’s ‘everyman’ killer in Dahaad and Darlings as well as some of Vikrant Massey from Sector 36. It’s a fascinating turn, because all the actor’s habits and tics from his OTT roles (some of which admittedly annoy me) add to the dual-personality pattern of this one. It helps that the film makes the brave decision to extend beyond the chase into the aftermath — in courtrooms and prisons — so that we feel the full force of a “whydunnit”. It largely succeeds, despite the childish vibe of the closing slate. Given the chapters ahead, I would hope that the ellipsis-coded nature of the storytelling defeats the exclamation-mark energy of its intent.