Suggested Topics :

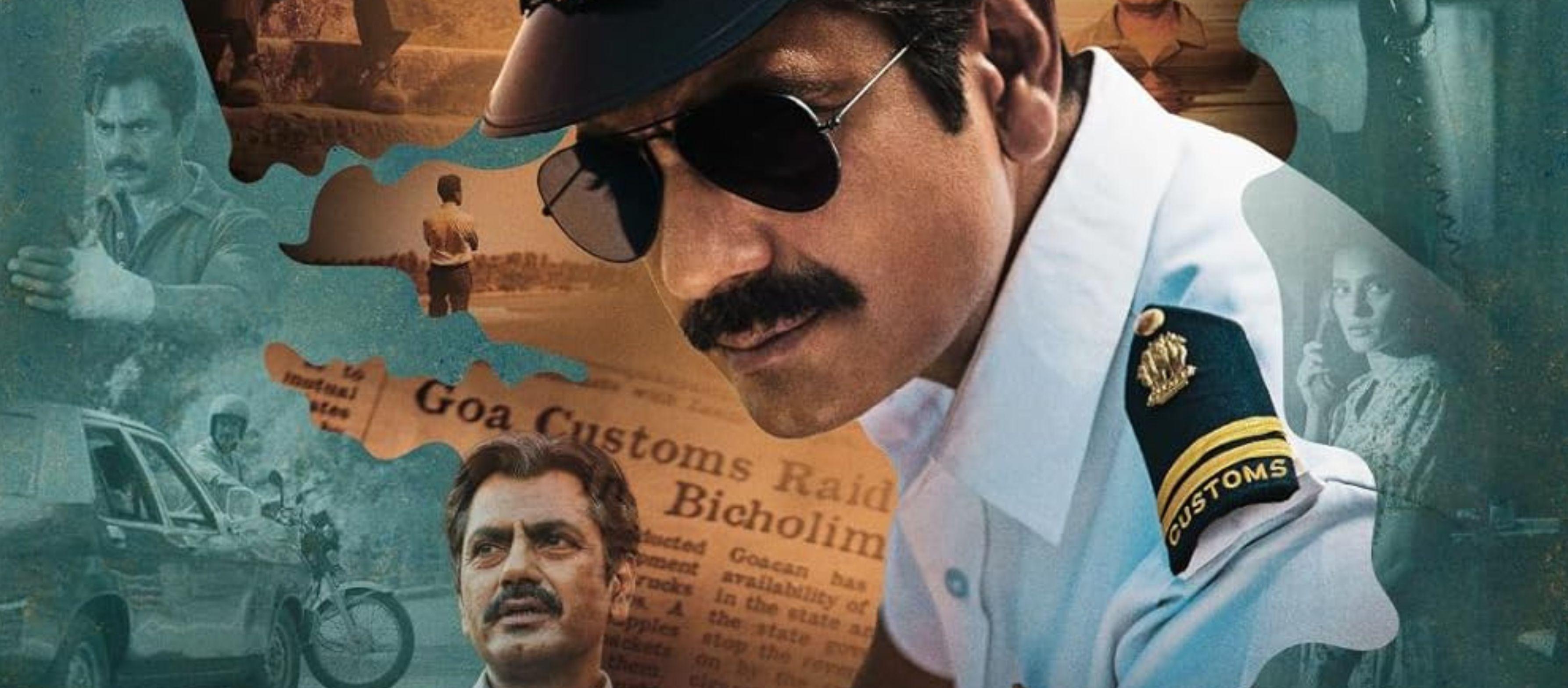

‘Costao’ Movie Review: A Promising Biopic That Snatches Defeat From the Jaws of Victory

The Nawazuddin Siddiqui-starrer expands our reading of heroism, but runs out of steam.

Director: Sejal Shah

Writers: Bhavesh Mandalia, Meghna Srivastava

Cast: Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Priya Bapat, Kishore Kumar G., Mahika Sharma, Gagandev Riar, Hussain Dalal

Streaming on: ZEE5

Language: Hindi

All things considered, Costao is not your cookie-cutter Bollywood biopic. It stars Nawazuddin Siddiqui as Costao Fernandes, the plucky Goa customs officer who killed the brother of a powerful minister in self-defense while trying to bust a gold-smuggling operation in 1991. This incident happens around 30 minutes into the two-hour-long film. At this point, he goes on the run; the Goa police as well as the politician’s goons search for him. The CBI soon puts him on trial for murder, and the gangster plans cold-blooded revenge. He is even attacked in a medical room by henchmen disguised as doctors. Most stories would stage his fight for innocence as an extension of this moment — as a tense battle for survival. One can almost imagine a high-pitched climax where he uncovers proof, exposes the smugglers, wins the case and clears his own name.

But Costao is not that story. The protagonist — a black belt in Karate and a former athlete who fancies football metaphors — spends the rest of the film paying the price of heroism. He also spends the rest of the film being irrevocably human. The CBI humiliates him every day; the widow of the slain criminal assaults him outside the courtroom; the sessions and high court judges uphold the accusations against him; he is forced to leave his home and move into customs housing quarters; the system abandons him; the gold is forgotten; the witnesses stay silent. Costao’s integrity is called into question. Apart from his loyal informer and empathetic boss, there’s nobody on his side. He has to pay for his own lawyer, too. Nearly a decade passes; it becomes a war of attrition, not plot points.

As a viewer, you keep wondering why his young daughter’s voice-over narrates the story. Like most precocious on-screen kids who address their parents by their first names, she refers to him as “Costao” instead of “daddy”. It’s a bit unnerving and creepy. But it makes sense when Costao reveals itself as more of a dysfunctional family drama unfolding through the lens of a lone-patriot movie. The case doesn’t take a toll on his personal life so much as his personal life being undone by a case. He can no longer afford to be a normal husband and father. He can’t attend his son’s sports day without spooking other parents and teachers. His little girl sees him get beaten up in public. He becomes a stranger to his kids (which explains the first-name gimmick). Most of all, his marriage suffers: his wife Maria (Priya Bapat) resents him for uprooting their peaceful existence and ‘choosing’ his job over them. One of the better scenes of the film features a loud showdown between husband and wife — and the silent estrangement that follows.

Basically, the momentum of a crime thriller and conventional patterns of a biographical film make way for a series of anticlimactic rhythms. The pragmatism of life takes over. Every time you expect Costao to resolve issues with a flourish or do something extreme, it doesn’t happen. Anti-drama is not an easy path to take, for both character and film-makers. Especially because there’s a long-term transfer and split involved; not many movies are culturally equipped to explore a journey of small defeats. The one-man-versus-a-system template is a familiar one, and it usually depends on our inbred perceptions of the genre. Credit to Costao for showing the unglamorous consequences of doing the right thing. The man’s workaholism and self-righteousness become his weakness.

Unfortunately, there’s a “but”. This “but” is similar across most ZEE5 productions. Costao isn’t cinematically equipped to explore the path it takes. The broader intent is fine, but the film fails to engage on a scene-to-scene level. It tries too hard to establish Costao’s reputation in the beginning. We know he’s well-respected and no-nonsense and not a big ‘process’ man, but the little details — like a moody dinner date with his wife; or a montage of his mission to stake out the smugglers — feel too curated to make any sort of deeper thematic impact. Ditto for the daughter’s voice-over trying to sound observational and older: for instance, comparing her dad to pure gold (“valuable but useless without dilution”) in his introductory shot.

There’s also the fact that the writing doesn’t commit to painting Costao Fernandes as a flawed hero — it eventually ends in the my-papa-was-not-absent-but-awesome vein, which defeats the point of his legacy. It’s almost too shy to delve into the anatomy of a broken family. It’s not a crime to confess that a hero need not be a great person, but just when Costao wades into unlikable-character territory, it pulls back. There’s a reluctance to humanise him too much; a child’s perspective of what went down further sanitises the struggle. The Family Man-styled portions don’t land with the sort of everyman wit and gravity that mark the lives of high-stakes professionals sparring with civilian emotions. The average choreography and awkward timing (like the cross-cutting of the verdict being read out) do not help the film’s case in the court of lawless aesthetics.

Siddiqui’s performance is one of the conflicting factors. He’s made a career out of playing deadpan Nana Patekar-coded strivers on screen; his portrayals of masculinity and small-town Indianness are at once satirical and serious. There’s always a sense that he approaches a commercial film from the space of knowing better. The downside of having such a distinct stamp is that it’s hard to detect characters — as opposed to personalities — within the acting. In other words, it’s difficult to perceive anyone but Siddiqui in author-backed roles. Sometimes it works (like in Serious Men and Raat Akeli Hai), but sometimes the auto-fiction is consumed by the reality of the actor — like with Manto and now Costao. The setting, period and real-world details melt away when he appears and does his thing. The trademark briskness is so common that the slightest sign of niceness (like a smile or softer delivery) feels performative, as if the character is pretending to be someone else.

It’s a very specific problem to have — where an actor’s talent begins to work against them. Superstars suffer from this all the time, so perhaps it says something that Siddiqui’s syndrome stems from being an alt-hero disruptor. On paper, he is Costao Fernandes. The metaphor of trying a man for being unorthodox and effective at his job is not lost on us. But there’s very little Costao left by the time the credits roll. It becomes just another story about an underdog’s toxic love story with his country. While it’s tempting to appreciate a Hindi biopic that refuses to be a one-note hagiography, Costao makes the bailable mistake of raising hopes only to dash them. Depending on who you are, the film swings between ambitious and disappointing. But it’s no longer about whether the glass is half full or half empty now — it’s the water inside that’s close to its expiry date.