Suggested Topics :

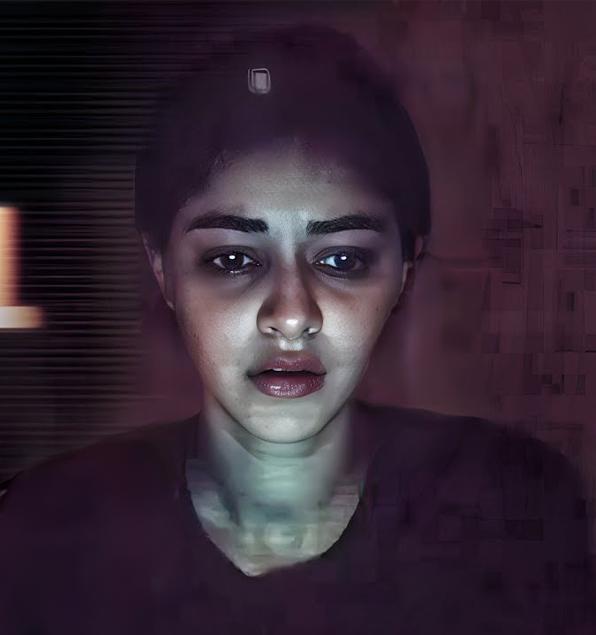

‘CTRL’ Review: Ananya Panday Anchors a Smart and Attentive Screenlife Thriller

It’s the kind of seamless actor-film fit that allows us to lament the imperfections of a culture without skewering it.

Director: Vikramaditya Motwane

Writers: Vikramaditya Motwane, Avinash Sampath, Sumukhi Suresh

Cast: Ananya Panday, Vihaan Samat, Kamakshi Bhat, Devika Vatsa

Streaming on: Netflix

Language: Hindi

In 2018, Aneesh Chaganty’s Searching put the life in screenlife. It marked the natural progression of ‘screenlife storytelling’ — a visual format where events happen entirely on computer screens, smartphones and cameras — into the real world. Until then, the horrors of technology had been literalised by the found-footage and supernatural genres. But Searching featured a father who looks for his missing daughter by following her digital footprints. His internet sleuthing reveals how little he really knew her; the technology he uses to find her is what had isolated her to begin with. Vikramaditya Motwane’s CTRL goes a step further; it expands the plausibility of the genre by unfolding in an age that puts the screen in screenlife. CTRL marks its progression into the reality of a virtual world — one where being watched is simply a natural consequence of feeling seen.

Nella Awasthi (Ananya Panday), one half of a Gen Z influencer couple, gets cheated on by her boyfriend, Joe Mascarenhas (Vihaan Samat). Enraged, she downloads an AI app — creating an assistant named Allen — to erase Joe from their shared life. Allen begins a 90-day task of deleting Joe from the couple’s thousands of pictures, reels and videos. He simultaneously manages her recovery, planning her comeback to ‘slay’ as a single social media ‘kween’. All is well until Joe actually goes missing, and Nella realises that this app is anything but harmless. In other words, imagine an influencer-culture baby of Her (2013) and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).

This premise does well to reveal the altered (or alt) vocabulary of modern existence. It starts with the title CTRL, which not only alludes to the app taking charge but also to how control is embedded in the very fabric of keypad living. Nella thinks she is at odds with an app, but she has herself earned a fortune in the currency of control. Her career is defined by the skill to influence strangers and be influenced by their needs. Her entire personality, including her relationship, has been governed by the commerce of content parading as the emotion of contentment. “I’m content” is more of an exhibition than an expression. Her video channel with Joe sold love as a subscription model, not a form of companionship.

When he goes missing, it is defined by Nella’s missing of — and her pixelated longing for — their attachment. Her idea of forgetting Joe, too, is rooted in the act of literally erasing him from (device) memory. This montage of digital expunging plays over a breakup ballad called ‘Uff yeh ulfat’; the sight of Nella watching Joe slowly vanish from photographs is so poignant that it’s unnerving. The implication being: if someone is not online anymore, did they really exist? Then, there’s the AI assistant whose name, Allen (voiced by a popular actor), is an anagram of Nella because his artificial intelligence is simply a subset of hers. He speaks in glitchy templates and phrases. Like her, he is also a tool to survey and influence; he mines data, she mines her life to turn it into data. Once Nella gets sucked into a conventional web of corporate conspiracy, whistleblowing and deep fakes, the message is clear: every identity comes with a username and password. It’s only towards the end that we learn that even ‘Nella’ is an anglicised twist on her legal name, Nalini. It’s like she moulds herself into a catchy concept to aid the logo of her relationship: Nella just sounds more compatible with ‘Joe’.

Another recent Hindi film, Dibakar Banerjee’s Love Sex Aur Dhokha 2, made a similar case against the Big-Brother-ification of culture and the algorithmic submission of society. But CTRL is more focused, trading rage and disdain for something deeper and leaner: resignation. There’s an inevitability about Nella’s fate that speaks to a generation torn between licensing out their identity and consenting to hidden terms and conditions. Regardless of her efforts, she is doomed to rise, fall and heal within the constraints of cyberspace. She can barely recognise herself if her face isn’t lit by the faint glow of a screen.

Nella is also so used to being on camera that she assumes that she is the story; she doesn’t quite sense her role in a broader story. One might even say that CTRL is essentially a film about Joe, his mistakes, and his connection to something bigger than him; Nella is just a character in it. It’s not different from how Searching refers to a father’s physical and psychological search for his daughter; he seeks her story by trying to find her. That we learn of Joe at the same time as Nella does becomes an indictment of how little they knew each other despite ‘creating’ a life together. But Nella’s main-character energy — a peril of her profession — ensures that she only sees his infidelity as a sign of their distance.

The few false notes of CTRL aren’t deal breakers. It’s a bit of a stretch that Joe Mascarenhas (whose namesake in Rock On!! cheats on his wife with rock music) is sort of a tech vigilante by night. That’s not to say he doesn’t look capable, but it feels like a convenient bridge between movie genres. The film uses him to zoom out of the situation and morph into a social thriller. Even if it reiterates Nella’s cluelessness about them, his double life is too detached, and its exposition is too far-fetched. Sometimes, the film’s quest for digital snappiness and rhythm doesn’t allow the events to breathe. While this reflects the quick discourse cycles and shortening memory spans of today, it often happens at the cost of emotional impact.

But the film’s detailing — both technically and narratively — goes a long way. For instance, when Nella checks with Joe’s sister, you can see that the history of their chat is limited to superficial birthday wishes and replies. There is no mention of Joe and Nella’s break-up, which implies that the sister might have resented Nella for turning his mistake into a spectacle. One of the text messages appears to be a spammy property ad, mere days after Nella moves into a swanky new Bandra apartment — common proof that all devices have eyes and ears. A whistleblowing journalist writes for a website called “Andolan”, which is the name of not only Motwane’s production company but also a nod to the political affiliation and anti-establishment slant of the publication.

CTRL is also a rare Hindi film (alongside last year’s Kho Gaye Hum Kahan) that gets the tonal and visual components of the social media landscape. It depicts the Internet without being condescending to the youngsters who thrive on it. Tricky things like going viral or getting trolled look fluid; slipping in a Yashraj Mukhate troll-rap song and a Tanmay Bhat podcast supplies the accuracy. It’s also a testament to the collaborative slickness of cinematographer Pratik Shah, editor Jahaan Noble and colourist Sidharth Meer that it’s hard to tell the precise moment CTRL goes from screenlife drama to a ‘normal’ film. At some point, the cameras and gazes cease, and all we see is the off-screen aftermath. It’s a big change, yet the jump is just about detectable enough to feed the film’s investigation of reality. It’s only visible if you wonder where the news tickers, call icons, or markers have gone.

A prime reason for this is also the clever casting of Ananya Panday — and, in turn, her intuitive performance. Panday is proving to be adept at choosing roles that complement her reality; she knows her strengths and plays to them. As a Gen Z actor herself, it’s no surprise that her rendition of Nella is shaped by a sense of lived-in experience. You can argue that there’s not a lot of ‘acting’ needed, but being yourself on a screen is difficult in a cautionary tale about losing yourself in screens. Her character in Kho Gaye Hum Kahan walked so that Nella could run, like and subscribe. Not only do the computers and phones feel like an authentic extension of Nella’s body and intellect, but Panday also infuses her persona with subtle subtext and behavioural patterns. Nella can’t tell the difference between who she is and who people follow. Forget love, even her rage and heartbreak are performative.

When she catches Joe red-handed, her meltdown almost feels like a skit; her reactions are subconsciously hardwired to reach a wider audience. Instead of processing the grief, she seems to be acting out her interpretation of what heartbreak should look like in a woke setting. There’s a tinge of regret on her face after all the bravado; you can tell that Nella wonders whether she left him for her dignity or her brand. There’s a sense that, if not for her job, she might have had a private conversation with her partner of five years instead of milking the melodrama of being wronged.

When she gets a life-shattering shock in the middle of the film, Panday is uncanny as someone who doesn’t quite know how to react to something so real. It takes a while to notice that she’s rarely seen with an actual person, yet it never looks like Nella is alone. She’s always surrounded by the illusion of company. This stems from the performer’s spontaneous comfort with her ecosystem. Even when we see texts exchanged or Internet rabbit holes being pursued for prolonged periods, Panday’s presence seeps into the screen. Nella’s reactions while typing, too, tell its own story. It’s the body language of a person who needn’t pretend to pretend.

Most of all, it’s the kind of seamless actor-film fit that allows us to lament the imperfections of a culture without skewering it. It would’ve been easy to stage Nella as an unserious Call Me Bae-like character, but as he did in AK vs AK (2020), Motwane employs satire to question our relationship with the politics of influence. That someone as ordinary as Nella can investigate a disappearance speaks volumes about a system that composes the language of control. It also says something about how we’re more attuned to spotting electronic footprints instead of nervy heartbeats. After all, it’s no longer about technology; it’s about the inability to feel human — or inhuman — without it.