Suggested Topics :

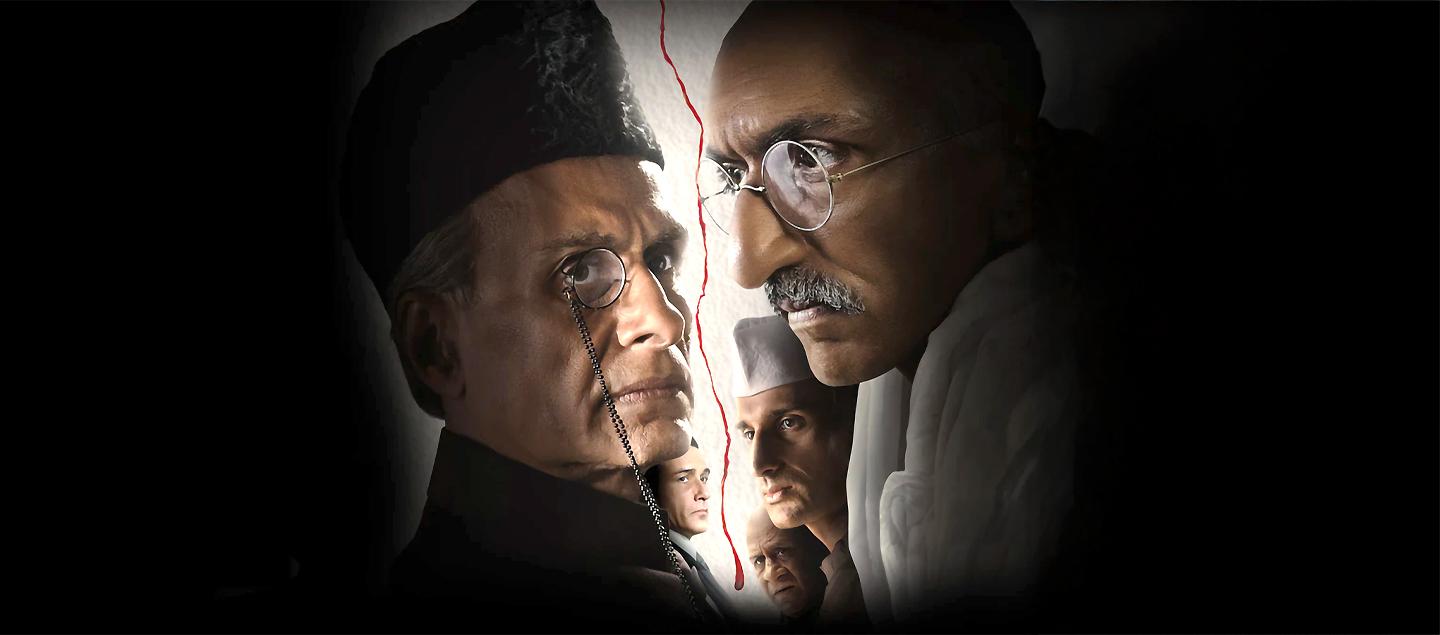

‘Freedom at Midnight’ Review: A Brave And Bulky Historical Thriller

Nikkhil Advani’s 7-episode Partition drama is ambitious, campy and politically expressive.

Director: Nikkhil Advani

Writers: Abhinandan Gupta, Gundeep Kaur, Adwitiya Kareng Das, Divy Nidhi Sharma, Revanta Sarabhai, Ethan Taylor

Cast: Sidhant Gupta, Chirag Vohra, Rajendra Chawla, Arif Zakaria, Luke McGibney, Cordelia Bugeja, Rajesh Kumar, Ira Dubey, K.C. Shankar

Streaming on: Sony LIV

Language: Hindi

As children, most of us learn to see 1947 as India’s finest moment. The event is simple: India gained freedom from the greedy British Raj and that’s that. As teenagers, we start to sense that perhaps it wasn’t all smooth and happy. With independence came the pressure to move out and grow up. But it doesn’t matter much because, either way, colonialism ended. As we get older, however, a full and bittersweet picture emerges: a nation is free, only to be violently divided into two on the basis of religion. It was never as simple as the British leaving or a newly born country celebrating its revolutionaries. This fuller picture has been molded — and revised — into shapeless stories by a future reeling from its scars. History is what happened, but these days, history is what we choose to believe.

In that sense, Nikkhil Advani’s Freedom at Midnight is an unusual entry in the Partition canon. Based on the 1975 book of the same name, the 7-episode series unfolds as a bureaucratic backroom drama situated in an anticlimactic and complicated year between the short-lived joy of independence and long-term despair of partition. It is rooted in a post-gut clarity of grappling with one question: now what? The freedom fighters are past their heroic primes; they’re now messy architects, angry and anxious and disorientingly human, often burdened by the chilling connotations of identity. They’ve reached the summit — a triumph that every Indian child will learn of. The series captures the moment they discover the real challenge is going back down — a journey that every Indian adult will strive to unlearn.

Freedom at Midnight is a difficult show to make. Firstly, it’s about politics. It’s handicapped at a narrative level. The drama almost entirely depends on verbose conversations, meetings, debates, speeches, decisions, exposition and heavy dialogue. Unlike The Crown, or closer to home, Rocket Boys, a chunk of the period staging is indoors: in grand chambers and corridors and offices. The stakes are exciting, but the process is not. As a result, the filmmaking feels the pressure to offset the bureaucratic theme — to make politics look faster than it is. For instance, a relentless ticking sound scores the static scenes, lest we don’t sense the tension between Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru’s Indian National Congress (INC) and Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League. Corny partition metaphors, like half a biscuit sinking into a tea cup, keep surfacing. The background music builds up to multiple crescendos, inflating the more ‘mainstream’ moments — like Lord Mountbatten entry shot as the last Viceroy of India, or Gandhi’s comeback montage to Delhi after stabilizing a broken Bengal.

I like that the show leans into the stagey and excessive tone. Indian productions tend to creak under the weight of historical authenticity, but Freedom at Midnight embraces its cosplay-ness. The imitations were never going to be “realistic,” so they remain a bit campy — not least Sidhant Gupta’s Nehru, whose colonial hangover and Hrithik-Roshan-coded diction change with the pitch of a scene. This is Gupta’s second successive Partition performance after Jubilee (2023); there’s something about the way he infuses vintage characters with modern mannerisms. He may not be ready for a role of such gravity, but the pulp-fiction of it all brings to mind the freestyle acting of a Ridley Scott movie. In contrast, Chirag Vohra’s Gandhi and Rajendra Chawla’s Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel are genuinely immersive turns. Chawla not only nails the Gujarati twang, he injects Patel’s shrewdness with pangs of paternal sincerity. Vohra capitalises on his Scam 1992 fame and delivers the most physically canny rendition of Gandhi in recent memory.

The catchy opening credits reflect the tone, too. The theme itself combines a rousing Western arrangement with the sentimentality of Indian instruments; the graphics range from the literal erasing of newspaper ink and the elasticity of a khadi string to borders of blood dotting the maps of Punjab and Bengal. Most of the English actors speak in ornate headlines. A nice scene features Nehru and Patel lost in the Viceroy’s huge mansion, breaking into laughter once they can’t find the exit. The symbolism doesn’t leave much to our imagination, but perhaps it doesn’t want us to imagine anymore. Nikkhil Advani might be a hit-or-miss film director, but he’s a refined showrunner with an eye on the discourse around him. He flirts with the Ae Watan Mere Watan syndrome — a condition in which progressive writing swallows the craft — but manages to reign it in.

That said, the show has its flaws. Not for the first time, Jinnah (Arif Zakaria) is a broad-strokes caricature whose personality is reduced to pipe-smoking, coughing, scowling and “I am the sole spokesperson of Muslims” rants. There are times when the writing tames him out of guilt — especially when he makes a case for a state of religious minorities rather than a religious state. Yet, the very next moment, he’s back to being a sociopath. The riots, too, become an extension of his image; the violence feels one-sided, with non-Muslims often at the receiving end. The simplification of his League stops inches short of bigotry, the kind this series is supposed to be an antidote to. Another screenplay issue is that, no matter how many negotiations take place, every episode ends with a “partition is imminent” cliffhanger. It’s hard to keep track of changing minds, sullen moods and shifting allegiances after a while. The execution tries to flaunt the complexity of the moment. At points, the show departs from its texture — like when the Mountbattens are traumatised by their visit to a shattered village — to reveal how those involved in the making and breaking of India were human.

The second reason Freedom at Midnight is a tough show to pull off is because it’s political. More importantly, its politics swim against the tide. In an age where every second historical drama takes potshots at Gandhi, Nehru and his INC successors, Freedom at Midnight has a set-the-record-straight vibe. That’s not to say it whitewashes them, but it goes to great lengths to normalise the party and convey that it was just as divided — and fragile — as the country they represented. There are no good and bad factions: some leaders want a unified India, but others are prepared to “lose a finger to save the hand”. Gandhi’s penchant for emotional blackmail, Nehru’s naive idealism and Patel’s subtle biases are portrayed as small parts of relatable wholes. The series doesn’t put them on a pedestal, but it also refuses to judge them through the lens of hindsight. Some scenes reach for sympathy-inducing histrionics, as if nobody except Jinnah is at fault. But regardless of who deals and wheels, everyone seems to have a conscience. The magnitude of the stakes is not lost on anyone.

The season finale, in particular, is cleverly compiled. The flashbacks of Jinnah’s early rivalry with Gandhi is intercut with a revenge arc that becomes a redemption arc. It feels like the origin story of a communal crack that, over the decades, morphs into a full-blown canyon. There are rifts and resignations, channel breakdowns and moral compromises. Yet, there’s a distinct feeling that everyone is fighting for their own truth; none of them can envision the petty ramifications of their actions in the 2000s. Once the ‘transfer of power’ plan is put into motion, the series mines the conflict between independence and identity. The Congress becomes the star of a dysfunctional family drama; they mull, disagree, sulk and err without being pigeonholed as heroes or villains in a victory that yields no winners. Freedom at Midnight is not done yet, both as a television drama and a historical flashpoint. The partition will end at some point, but the severance continues to provoke dark beginnings. History is what’s happening, but in this case, history is what we choose to recognise.