Suggested Topics :

‘Binny and Family’ Review: Home is Where the Art is

The film is sweet, surprisingly sensitive and self-contained, despite its several moments teetering on the brink of succumbing to Bollywood excesses.

Director: Ssanjay Tripaathy

Writer: Ssanjay Tripaathy

Cast: Anjini Dhawan, Pankaj Kapur, Rajesh Kumar, Charu Shankar, Himani Shivpuri

Language: Hindi

Binny and Family isn’t supposed to work. It has all the signs of a self-righteous family entertainer. It ends with an Orkut-era quote (“happy family is the foundation of a happy nation”) by one of its own producers. The climax revolves around an inter-school drama contest. The second climax revolves around a preachy Hindi monologue to a British audience; if it brings to mind the ‘Vande Mataram’ moment from Karan Johar’s Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham… (2001), it’s because the catchphrase of Binny and Family is “it’s all about loving your grandparents”.

Moreover, half the Hindi film industry is thanked in the opening credits. Its release was pushed by a week to accommodate a “beautiful end-credits song”. Its premise is centred on a generational clash between modernity and tradition. Modernity is an 18-year-old NRI who smokes blunts in the toilet, modelling herself after Zendaya, listening to rap and partying every night; tradition is said teenager’s Bihari grandfather converting mashed potatoes into spicy aloo chokha at a London pub. You know how it goes.

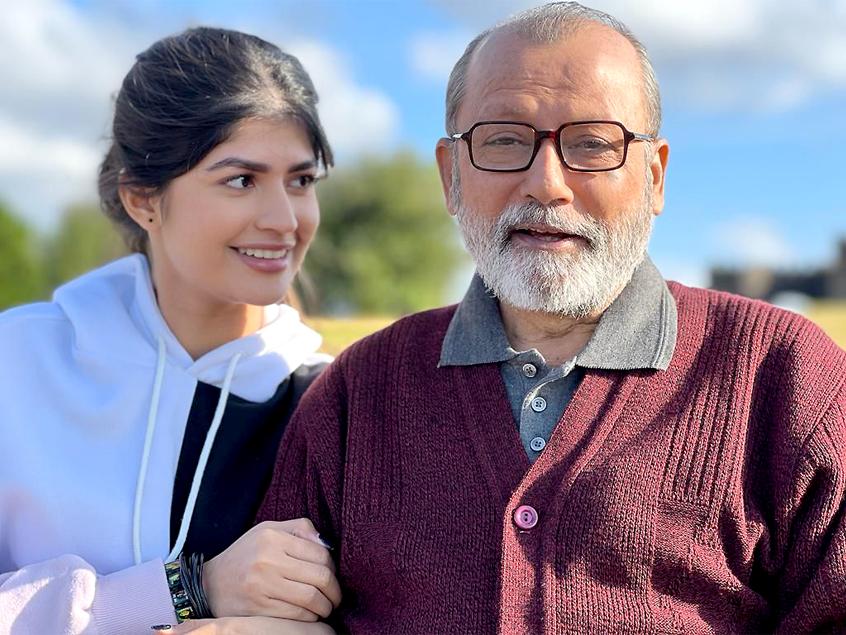

But somehow, against the odds, Binny and Family works. The film is sweet, surprisingly sensitive and self-contained. Even though it opens with a shot of a girl sprinting away from home and screaming into the void, it retains a sense of perspective and scale. The conflicts are mundane, not melodramatic. The biggest problem of the young protagonist, Bindiya ‘Binny’ Singh (Anjini Dhawan), is that she has to share her bedroom with her visiting grandparents (Pankaj Kapur and Himani Shivpuri) every year. All she wants is her own space. Things come to a head when one of them gets sick — and the arrangement threatens to become permanent. She can’t understand why they should be treated abroad; she’s convinced that their health is an excuse to escape their own loneliness.

It’s tempting to dismiss Binny as an entitled Gen Z brat, but the film deftly slips in some context: this is her fifth year in London after being uprooted from Pune, so the prospect of further displacement makes her lash out. Again, there are no flashbacks of her childhood — we learn of this from her parents’ regular chats. As a result, Binny’s father, Vinay (a lovely Rishi-Kapoor-ish Rajesh Kumar), is torn between old-school respect for his parents and new-age empathy for his daughter. Much of the film is shaped by this modest but heart-wrenching choice between the past and the future; between duty and desire; between roots and saplings; between caregiving and caretaking. One tragedy later, Binny finds herself at the crossroads of adolescent guilt and adult compassion. Her journey is so plausible that it's unsettling; the film doesn't pretend to be larger than that.

Most Indian stories tend to romanticise the old and condemn the young. Teens are often treated as aliens who speak in incoherent slang. But Binny and Family offers both sides some room for improvement. The gaze is balanced; it seldom judges Binny for being lost and rebellious, just as it doesn’t glorify the grandfather for being stubborn and patriarchal. The mashed potato scene is followed by Binny learning to eat with her hands to make the old man feel comfortable; he, in turn, takes etiquette classes to learn the way of the land. His Indian-ness isn’t used to take a swipe at ‘Western values’ either. There are familiar gags (“What kind of doctor is this Dr. Dre?”), but there’s also a sense of gravitas about how every generation is conditioned to think in a certain way. It brings to mind the measured gender politics of Laapataa Ladies, where each of its female characters strives to change while retaining the essence of who they are.

Even the South-Asian immigrant experience is addressed through the track of Binny’s parents. You can tell that they’re so taken by the cultural freedom of a new country themselves that they’re struggling to impose a consistent parenting style on Binny. Some of the funnier montages feature Vinay and his wife Radhika (Charu Shankar) pretending to be ‘sanskari’ the moment his parents arrive; the bar and party photos are quickly replaced by religious idols and books. It reminded me of the brief but charming scene from Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), where a homemaker and her two daughters routinely jive to a Eurodance track every evening only to switch to an Indian oldie the second her husband returns from work.

The film also alludes to the knotty tensions in a family where entire relationships are limited to distant visits. At one point, Binny mentions that she’s not had the chance to feel the warmth of a grandparent because she’s only ever seen them as houseguests with opinions; they’ve never had an opportunity to connect because most of this time is spent reinforcing social stereotypes and familial labels. It’s a mature observation from a budding writer who instinctively quotes Martin Scorsese (“the most personal is the most creative”) on stage. She writes a play inspired by the open-mindedness of her grandfather, as opposed to Amitabh Bachchan’s character writing a novel inspired by the cruelty of his sons in that bonafide classic for desi parents, Baghban (2003).

Evidently, Binny and Family does a lot of things right by virtue of not doing them wrong. There are several points where the narrative seems to be on the brink of succumbing to Bollywood excesses. For example, the death of a character is a big turning point, but the death itself becomes an off-camera mention; only the aftermath is relevant to the film’s emotional arc. Similarly, the drama competition isn’t milked; the play is suggested rather than shown, and the results aren’t dwelled on. (I was half-expecting a Dil To Pagal Hai moment, where an altered stageplay catalyses a happy ending.) The grandfather is often present during Binny’s other problems, but his old-fashioned masculinity is rarely staged as a rescuer. The track of Binny’s high-school crush, too, stays subdued; her Gujarati-influencer best friend is strangely endearing, not least when he chills with her over a plate of khandvi on his car bonnet. Their banter doesn’t try too hard; it plays a key role in communicating Binny’s thoughts and insecurities to the audience.

Another scene features Binny and her grandfather discussing love on a bench at night. Any actor other than Pankaj Kapur might have made this exchange sound a little pretentious. In fact, anyone else might have made the man’s willingness to evolve look like a cosmetic movie trope. But Kapur has this uncanny knack for letting silences do what a film’s background score and screenplay can’t. At times, it’s just the miles in his voice and the creases on his forehead that put the family in Binny and Family. His character is a fantasy in the context of the average Indian boomer, but he allows the viewer to enjoy the man’s transformation.

He also allows a newcomer like Anjini Dhawan to be — and excel as — a version of herself. She owns the lingo without flaunting it. There’s a natural curiosity — an uncharted rawness of sorts — between her and the adults of the film; it actually looks like she’s teaching them a thing or two about not having a mental filter. Dhawan’s performance is in perfect sync with a story that teases our preconceived notions of both the actress (she is Varun Dhawan’s niece) and the character she plays.

All of which is to say that Binny and Family does its job. I usually get defensive when I see Baghban-inspired themes in a mainstream drama. Perhaps it’s because, like most Indian men, I tend to blame my limitations on my elders for ‘holding me back’. Or maybe it’s because I’m reaching an age where I’m unsure about which side to root for. But Binny and Family slowly punctured my skepticism. It made me believe, if only momentarily, that a utopian middle ground can exist. I didn’t care for the cringey message about happy families, but I cared for its unwitting ode to dysfunctionality. It need not be the loud and cinematic kind of imperfection. Sometimes, it's just the small regrets and resentments — supplied by the courage to address them. This is, after all, a feel-good film about life’s most common feel-bad attachment.