Suggested Topics :

‘Jugnuma – The Fable’ Movie Review: A Bewitching Brew of Superstition and Storytelling

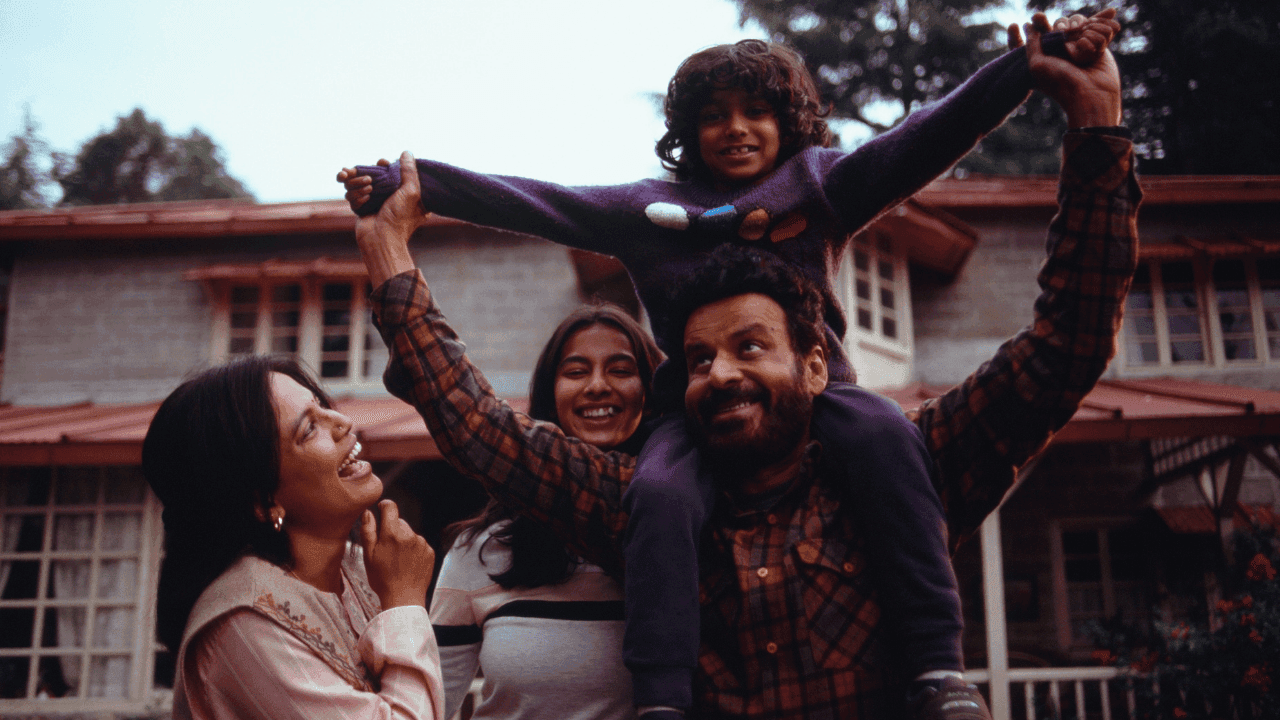

Starring Manoj Bajpayee, Raam Reddy’s second feature is a myth-busting triumph of beauty and curiosity.

Jugnuma – The Fable

THE BOTTOM LINE

One of the finest Indian films this year

Release date:Friday, September 12

Cast:Manoj Bajpayee, Priyanka Bose, Deepak Dobriyal, Hiral Sidhu, Tillotama Shome, Awan Pookot

Director:Raam Reddy

Screenwriter:Raam Reddy

Duration:2 hours 39 minutes

Raam Reddy’s Jugnuma – The Fable opens with a long, unbroken shot. It’s the summer of 1989 in a Northeastern Himalayan town, and Dev (Manoj Bajpayee), a middle-aged and soft-spoken landlord, starts his day by walking to the toolshed in the backyard of his colonial mansion. It looks like an average routine. On the way, he greets his wife Nandini (Priyanka Bose), his playful son Juju (Awan Pookot), his two dogs Jack and Alex, and a couple of locals. The camera follows him into the dark shed, where he straps something onto his body and strolls down a path. He’s wearing what looks like mechanical wings and, before it fully registers, he casually jogs off a cliff edge, flaps those wings and flies into the valley. This is how he surveys the thousands of acres of the orchard estate inherited from his grandfather. It’s pesticide season; his route is wider. I’ve seen many striking movie beginnings, but none like this, where reality nonchalantly collides with fantasy in the same breath. In the next few minutes, we know why.

We hear a narrator from 35 years later, describing this seemingly utopian life of Dev and his family. The shot unfolds just like that: a grainy (16mm) and stream-of-consciousness memory that’s too old to separate mundanity from magic. We learn that the rickety voice belongs to Mohan (Deepak Dobriyal), Dev’s loyal estate manager. Dev’s teenage daughter Vanya (Hiral Sidhu) arrives from the hostel for her holidays, but soon, the tranquility is punctured. Parts of the estate get engulfed by mysterious forest fires: first trees, then bushes around the bungalow. Nobody knows who it is. Tensions rise; Dev distrusts his employed hands, they distrust him, Mohan is politely laid off, superstitions are activated, a corrupt cop adds fuel to the fire(s), a mother (Tillotama Shome) narrates a fairytale to her son, and a group of horse nomads is attacked by the villagers. Not even Dev’s flights across the valley yield answers. Simultaneously, Vanya’s fascination with one of the nomads triggers a sexual awakening of sorts. Every now and then, Mohan’s voice re-emerges, almost as a reminder that someone else — presumably his grandchild — is listening to his yarn in 2024.

Much of Jugnuma is both concealed and defined by its hypnotic visual language. It’s like hearing a story with your eyes. Reddy and DOP Sunil Borkar capture a bygone moment in time, but the cumulative nature of this moment is never beyond doubt. There’s always a sense that the film remains faithful to the elasticity of the narrator — the melange of the past and future, heightened folktale and human truth, reveals the toll of 35 more years of living for someone like Mohan. His storytelling is a fluid aggregate of the setting he remembers and the world he went on to inhabit; the lines are blurred. He is speaking as a wary veteran whose worldviews bleed into the fable. You can tell that his experience, biases, traditions, dreams and influences subconsciously combine to form a socio-political portrait of a more contemporary India.

The hints are embedded in the slow-burning conceit. The conflicts are familiar. The vast orchard estate symbolises a cultural landscape and country inherited by the majoritarian ruling class — both in terms of caste and religious privilege. The owner first questions his own downtrodden ‘citizens,’ who in turn cast suspicions on a tribe of spiritual outsiders and border migrants who were minding their own business. When the law of the land fails, he summons the military: a colonel and his team take over the investigation. Even the surrealism of the family and their surroundings makes sense from this perspective. The names — Dev, Nandini, Vanya, Mohan — are a sign; they represent the shapeless role of lore in a nation that’s wired to conflate history with Hindu mythology. Reddy’s writing reclaims the divide between the two. The bedtime story that the local tells her son revolves around fairies who might be stuck as misfits in the wrong dimension. It’s almost a way of implying that Indians across eras have weaponised faith and gods so hard that maybe the epics have been unwittingly displaced by life. It’s like watching the sky reduced to the earth that pollutes it.

We imagine them as higher beings who look and behave differently, but the tragedy of them adopting the trappings and fears of the real world — oblivious to their own powers — is beautifully staged. Instead of oozing divinity and blessings, they’ve been forced to misinterpret their job profiles; they become settlers, and surrogates for the very establishment that leverages their legacy. The film simply captures a few weeks in which the fabric is ruptured and the balance threatens to be restored. At some level it’s a poignant and Shyamalan-esque eco-drama, where the social conditioning of the narrator determines the compatibility between fiction and the humans that distort it. If we keep telling ourselves stories, these stories are primed to lose their wings. When Dev leaps off the cliff edge every morning, it’s normalised because we think he’s keeping an eye on his property. The film seamlessly reaches a stage where the surveillance swoops acquire new, coming-of-age meaning — like using ‘work’ as a front to preserve one’s essence. He’s flying because he’s supposed to.

The performances in the film play out as their own parables. Each of the characters seems to be coming to terms with the possibility that they’re incomplete; they’re searching for themselves as much as the culprits. Whether it’s Priyanka Bose’s quiet and ambivalent presence as Nandini or Hiral Sidhu’s subversive turn as the rebellious teenager, they allow the family to exist both introspectively and retrospectively. Dobriyal lends Mohan a measured but mystical sense of compliance, and Shome’s scene-stealing cameo traces the outline of the story within the story. Bajpayee plays Dev as a patriarch who’s snapping out of a spell without realising it. It’s as if he’s drawn to the fires instead of feeling bad about them. There are layers to the way he reads the epiphany of his character.

The little details — like how physical and busy Bajpayee is when he has no dialogue or when the focus is elsewhere — work wonders (and expand the wonderment of scenes). There’s a lived-in intrigue about Dev that makes him look complicit and vulnerable at once. Even when he’s not in the frame, his confusion bleeds into the hidden designs of the premise. It’s a deceptively malleable performance that turns the meditative quality of Jugnuma into more than an aesthetic. The triumph of the film is that it seems to have no preconceived notions of what it’s about; it almost gets surprised by the way it unfolds. The reluctant protagonist is at the mercy of his teller, yet Dev’s disenchantment with the estate somehow reflects a quest to belong. It’s a homecoming disguised as a reckoning. After all, times are so dire that even mythology suffers from an identity crisis. Even fables are hoping to be rescued.