Suggested Topics :

Indie Cinema in India Lost Theatres First. Then, Streaming Too

With mid-tier commercial fare staking its claim on OTTs, and theatrical avenues closing fast, independent cinema is once again back to where it began: on the margins.

Once upon a time, streaming was the promised land.

In a market where the only parameter for success was the box-office earning — anywhere between ₹170 crore to ₹250 crore for blockbusters or ₹67 crore to ₹84 crore for mid-budget films — streaming offered a space for a content revolution. Whatever was too left of mainstream for the multiplex, too sharp for the censor board or too regional for the Hindi belt was welcomed.

In India, where independent filmmakers had long been ignored by the theatres, platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, JioHotstar, ZEE5 and SonyLIV became something of a lifeline. “It felt like we could finally tell our stories without fighting the same gatekeepers,” says indie filmmaker Sumanth Bhat, who made the Kannada film Mithya, recalling the early days of the streaming boom. “We thought we had found our place.” But the habits, tastes, and definition of “mainstream” shifted — almost overnight.

By 2022, theatres were back, but not for everything. Mid-budget films, once the backbone of Indian storytelling, were vanishing. Spectacle had taken over. RRR, KGF: Chapter 2, Ponniyin Selvan: Part I, Vikram, Brahmāstra: Part One - Shiva. All thunder. No whispers.

And in 2023, the ceiling blew off entirely.

Shah Rukh Khan delivered three films in a single year, with Pathaan and Jawan alone making over ₹2,122 crore worldwide. Gadar 2, a throwback sequel nobody expected to explode, did just that. And Animal — a three-hour primal scream — closed the year with box-office numbers north of ₹500 crore (its total box office earnings were ₹934 crore).

In 2021, the highest-grossing Indian film was Pushpa: The Rise, an audacious Telugu-language actioner headlined by Allu Arjun. The film reportedly made ₹365 crore in just 50 days. It became a phenomenon. What’s notable is that Pushpa made almost the same amount of money as Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani would a couple of years later — ₹357 crore worldwide. But in 2023, Rocky Aur Rani’s earnings barely registered as a blip. That’s how fast the metric shifted. Anything under ₹500 crore felt like a footnote.

“An uncertain industry always returns to formula,” says one insider. “And the formula now is go big...or go to streaming.”

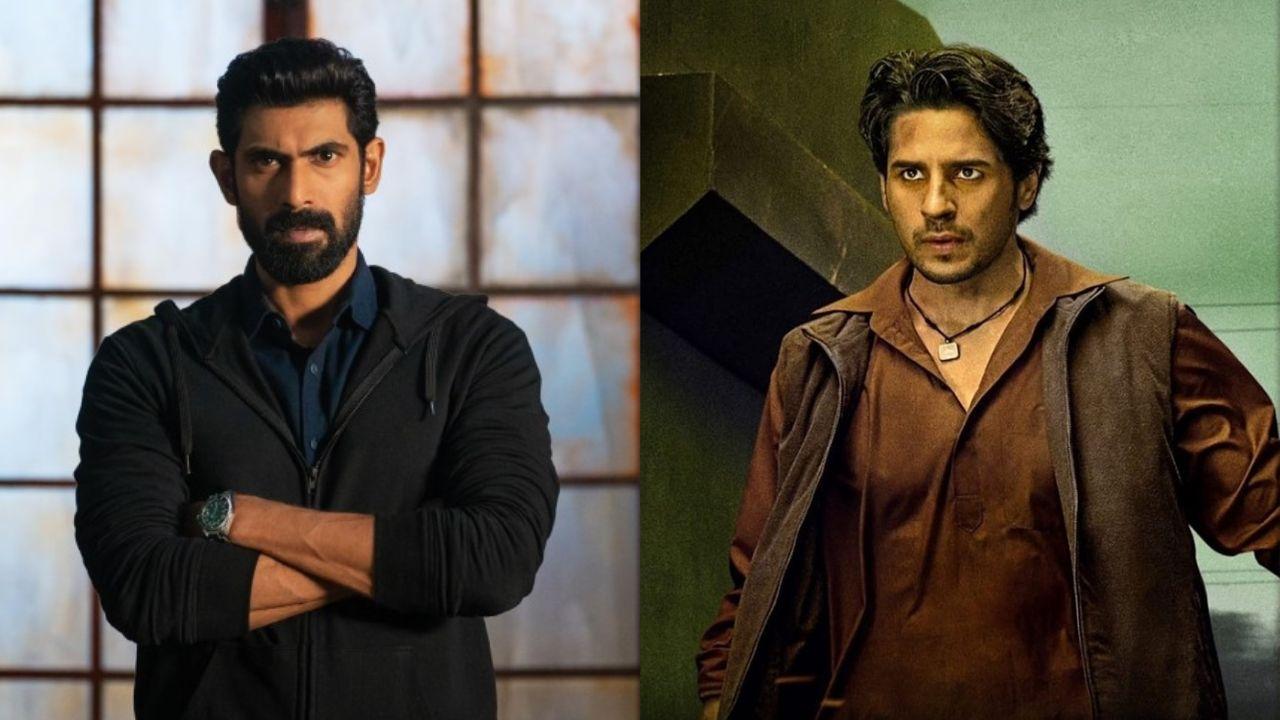

But even that equation had a hidden catch. A space where small films once lived — projects without stars, without marketing blitzes, without franchise-ready IPs — was now being colonised by the mid-tier. The Sidharth Malhotras (Mission Majnu), the Rana Daggubatis (Rana Naidu), the fringe Bollywood fare that suddenly became too “small” for theatrical release became the big bet on OTT platforms.

“Streaming became formulaic when the content that was considered too small for the ₹500 crore gross moved to streaming,” the insider added. “Obviously, a streaming film with a Bollywood star will attract more viewership than the content-forward stuff. People come for the stars.” Netflix’s own engagement report from December 2023 proved this point: Rana Naidu and Mission Majnu topped the charts. The algorithm didn’t lie. And suddenly, indie cinema didn’t just lose theatres, it lost streaming too.

The Never-Ending Hustle

In 2023, Jayant Digambar Somalkar made Sthal, a modest Marathi film set in a small village and told with stunning restraint. It premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and won the Netpac award for best film. Sumanth Bhat’s Mithya played at the Mami Mumbai Film Festival and travelled to several others. Harshad Nalawade’s Follower debuted at the International Film Festival Rotterdam. All elegant indie films, all made in 2023. All three released in Indian theatres in 2025. Why even bother? The tide had turned. The haven was no longer safe.

For filmmakers like Bhat, this shift has been devastating. “I made Mithya for the OTT space. I never thought of a theatrical release,” he says. “We can’t be delusional. A film like this has an audience, but it may not be a theatrical audience. People might love the film, but that doesn’t mean they’ll leave their workspace, go through Bengaluru traffic, bring their families, and go watch it.”

And yet, a theatrical release became non-negotiable. “There’s this mandate now: You have to do a theatrical run for OTTs to even consider your film,” Bhat says. “It’s just for consideration. There’s no assurance they’ll buy it. But you still have to spend on marketing and distribution — sometimes as much as your production budget.”

The irony stings. “The ‘first day, first show’ gets cancelled because no one turns up. Maybe the second day they give you a chance, but by Sunday, you’re out of theatres,” says Bhat. In the same breath, Bhat offers the heartbreaking truth that indie filmmakers now live with: “We’re already struggling to recover a small amount. And yet, we’re asked to spend half the budget on release — which you’re already mentally forfeiting — because you know you’re doing it only to get OTTs to look at it.” And then? Sometimes, they still don’t.

“Why should a producer lose money just because I want to make a film that’s personal to me?” asks Bhat. After years in IT and design, Bhat shut down two successful companies in Udupi, Karnataka, in early 2020, believing the time had finally come to make films. “I had harboured this dream for over 15 years, trusting the OTTs — and they were actually commissioning films back then. Buying films without even worrying about theatricals.” Then the pandemic hit. “By the time we recovered from that, the entire ecosystem had changed.”

“Indie filmmakers are not making these films to make supernormal profits,” Somalkar says. “But we should at least break even. Right now, even that is looking hard.” The filmmakers are now faced with a paradox: They’re forced to enter a system that has already rejected them, just to gain access to a platform that once existed to bypass that very system.

There was a narrative renaissance in Indian cinema from 2015 to 2020; the post–Ayushmann Khurrana, post–Rajkummar Rao wave. Everyone agreed that “content is king” was the path forward. Narrative-driven films found applause, awards, and even an audience. But the pandemic flipped the coin. Content wasn’t king anymore; content had to dance.

“We’re so consumed by what a theatrical film is supposed to look like that it has changed the grammar for cinema,” Somalkar tells The Hollywood Reporter India. “Even the people who loved my film, Sthal, came out and told me, ‘If you had added a couple more songs, we would’ve totally enjoyed it more’, and I couldn’t help but laugh,” he adds. And even if you clear the first hurdle — surviving the Friday slaughter and getting a streamer to pick it up — there’s still no promise of safety. “When it comes to Marathi or regional films, there are very few buyers,” says Somalkar. “Zee and Sony operate on revenue share. Amazon and Netflix rarely acquire them. Even JioHotstar follows the revenue-share model.”

In the revenue-share model, streamers host the film and pay the filmmaker a small amount — typically ₹4 to ₹8 per view or per hour watched — based on audience consumption.

That means the filmmaker takes on the risk and shares little of the reward. “Amazon doesn’t even acquire them outright. All the Marathi films you see on Amazon are on a revenue-share model. Netflix hardly acquires any unless it’s made by someone like Chaitanya Tamhane,” Somalkar adds laughing. And that’s assuming you’re even allowed to tell the story you want to tell.

“We really pinned our hopes on OTTs — that at least our films could come out somewhere. And that didn’t happen,” says Follower director Nalawade. For filmmakers like him, streaming was the last frontier for free expression. “Indian independents are known to push the boundaries a bit, right? With ideas, with the kinds of stories we go into,” he says. “And because of certain incidents that happened with streamers — where they were attacked for putting out a certain kind of content — they became cautious. That’s the second blow.”

The first blow was the economic squeeze. The second, the ideological muzzle. “Post-Tandav, things really started shifting for OTTs. They became very cautious.” In Tandav, a moment that referenced religious iconography snowballed into legal trouble that resulted in Amazon India seeking anticipatory bail for Aparna Purohit, Amazon Prime Video India head, and Ali Abbas Zafar, the show’s director.

That caution, he says, bled into acquisition strategy and left indies in the lurch. “Naturally, that affects independent films. Because independent films are trying to tell stories that are politically and socially uncomfortable. We are telling stories that hold a mirror to society,” Nalawade explains. “That was kind of a downfall for independent films.”

Risk is a liability. Provocation is unwelcome. Revenue must be assured. Platforms are increasingly reluctant to back a film that lacks big names and asks big questions. If you’re quiet, you might be ignored. But if you’re loud, you might be dropped.

Sundance, and Still Scared

If all of this wasn’t already dispiriting enough for the indie filmmaker, there’s now a new twist in the tale. A source in movie marketing told THR India that some streaming platforms are actually asking filmmakers to pay them to host their films. “This is absolutely ridiculous,” says Nalawade, fuming. “It’s not like distributors are asking for money because a theatrical release requires infrastructure. What is streaming charging for? Cloud storage?” He laughs, in disbelief. “It’s just a big hard drive.” The disbelief rankles more when you listen to Rohan Kanawade, the director of Sabar Bonda, a tender, offbeat queer drama that made history earlier this year. It became the first Marathi film ever to premiere at the Sundance Film Festival and went on to win the “World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic” at the event. But Kanawade, even in triumph, sounds hollowed out.

“What it took to make that film was five years of our life. And the main producer had to mortgage his house,” he says. “I was scared while making this film, even though we were spending this much money. I was really sad because, hearing the stories of my other filmmaker friends, I was scared. What if it doesn’t get a theatrical release? Or what if, later on, streamers don’t take it? What will happen?” He pauses. “I mean, I really wanted to enjoy the journey of making my first film, but I couldn’t. Throughout the making of the film, I was really worried. I see all my other friends who have already made their films also in the same boat.”

“I don’t know what we can do about it,” says Kanawade. That question — what can be done? — hangs heavy. In the same year that Sean Baker stood on the Oscar stage as Anora swept the awards and pleaded, “If you’re trying to make independent films, please keep doing it.... Long live independent film”, filmmakers in India are struggling to stay afloat. To put it in perspective: Anora was made on a small budget of $6 million. Harshad Nalawade’s Follower was made for ₹22 lakh, roughly $26,000. To be unable to recover even that much is not just unsustainable. It’s a tragedy.

THR India reached out to streaming platforms Amazon Prime Video, Netflix, Zee5, JioHotstar, and SonyLIV to ask what steps — if any — are being taken to support or even acknowledge this crisis. All platforms declined to comment.

With mid-tier commercial fare staking its claim on OTTs, and theatrical avenues closing fast, independent cinema is once again back to where it began: on the margins. Except this time, there’s no movement. No streaming revolution to save it. Just voices waiting to be heard.

To read more exclusive stories from The Hollywood Reporter India's May-June 2025 print issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest book store or newspaper stand.

To buy the digital issue of the magazine, please click here.