Suggested Topics :

Nikkhil Advani on 'Freedom At Midnight' and 'Revolutionaries': I'm Historied-Out'

The filmmaker talks about his treatment of Partition history in 'Freedom At Midnight' Season 2, balancing historical viewpoints, and his upcoming series on Indian revolutionary fighters

(Mild spoilers for the new season of Freedom At Midnight)

Partition was the dark dawn (the spotted, night-bitten dawn, in the words of Faiz Ahmad Faiz) that loomed at the end of Freedom At Midnight. It was the saddest of cliffhangers. Nikkhil Advani’s series, which premiered its first season in 2024, is about the complex circumstances leading up to and after Independence. Adapted from Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins’ non-fiction book, the show, in its sombre concluding chapter premiering on January 9 on SonyLIV, wastes little time in getting down to it: the winners begin to look like losers at history’s gambling table; the price of liberation was fracture and fratricide.

Advani, a Sindhi whose family migrated from Pakistan to Bombay after Partition, understands the deep psychic toll the event took on the subcontinent. "My grandparents were luckier than most because my grandmother’s father was quite well-to-do, so the whole family and whoever else he could accommodate were bundled up on a flight to leave from Karachi."

Advani's paternal grandfather was employed at Habib Bank Limited and was entrusted with carrying a money belt to give to the branch office in Bombay. The bank had shifted its headquarters to Karachi in 1947 at Jinnah's behest.

"While my grandmother always told us this story to talk about my grandfather's honesty and value system, there were times I saw her lament that he could have kept the money, and it would have saved decades of hardship after they migrated."

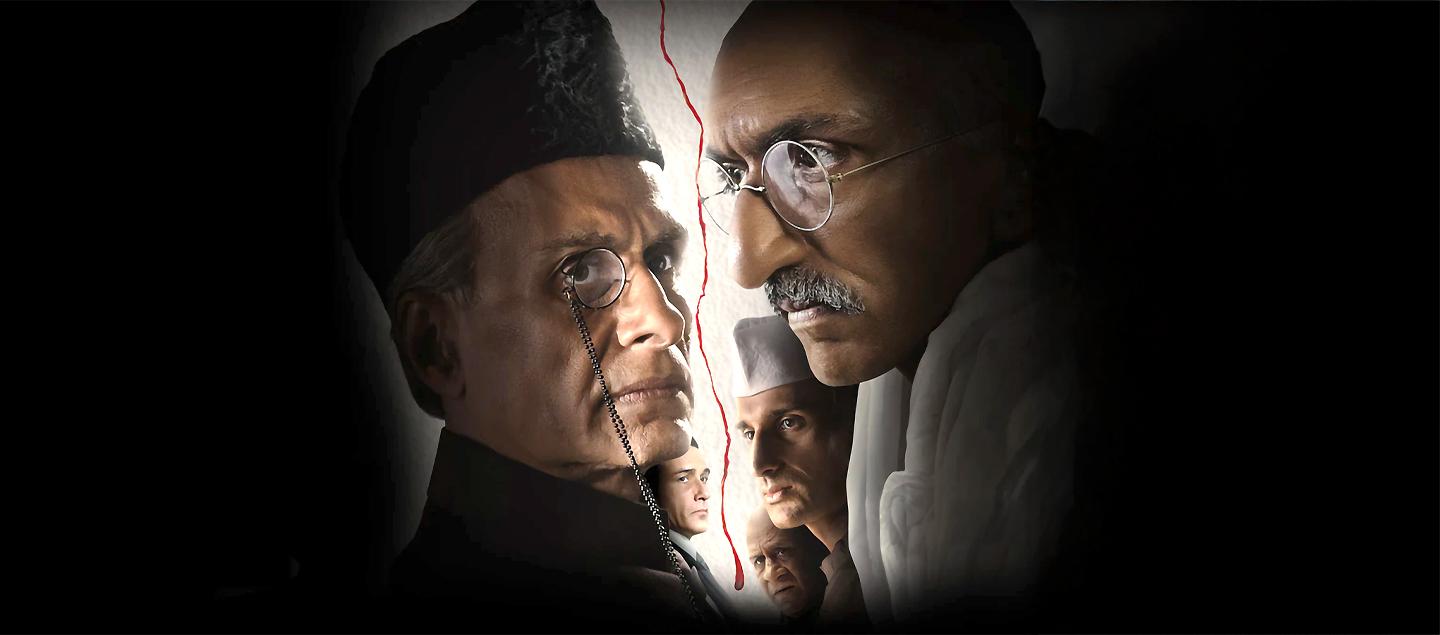

The first season of Freedom At Midnight was praised for its narrative density, the complex, fine-grained portrayal of historical figures like Gandhi, Nehru, Patel and Jinnah, and the grand sweep of events and emotions, while drawing criticism for its predominantly one-sided depiction of communal violence. Season 2 covers extraordinary ground, from the drawing up of the Radcliffe line to the butchery and bloodletting that led to the largest mass migration in human history. All along, a young man, angry and embittered, makes his way to Birla House.

This is, by any measure, the biggest production of Advani’s life. Both seasons were written and shot in a single stretch; Advani worked with a team of six writers, with Abhinandan Gupta leading the adaptation work. The opening episode of S2 focuses on the messy, unfathomable business of splitting a nation in two. In their book, Lapierre and Collins riff on the grotesque absurdity of the undertaking: not just rivers and railways or the army and treasury, even the smallest of public assets were bitterly haggled over. In Lahore, for instance, a Superintendent presided over the division of the police band's equipment, down to the last 'trombone'.

"I wish I had more time to depict the full scope of the batwara," Advani says. "There is a passage about public libraries, about how individual books like the Encyclopædia Britannica were ripped in two between India and Pakistan."

The most entertaining stretch in the new season is the integration of the 565 princely states into the union—a mind-melting challenge taken on by Sardar Patel (Rajendra Chawla) and executed by VP Menon (lovingly played by KC Shankar). Advani unearths some colourful details in this stretch, like how the Nawab of Junagadh was exceedingly fond of his pet dogs, or how Menon—a teetotaller from Kerala—developed a whiskey habit while concerting with the Maharajas.

Junagadh also echoes into the episode on Kashmir, with Mountabben pressing on Nehru's conscience to promise a plebiscite once peace was restored in the valley (Maharaja Hari Singh, under siege from Pathan tribesmen backed by the Pakistani Army, had signed the instrument of accession). India then took the dispute to the UN Security Council.

"The United Nations resolution mandated demilitarisation from both sides for the plebiscite to take place. As Menon reassures Patel at the end of the episode, Pakistan will never leave their occupied territories in Kashmir, so the plebiscite will never happen."

For all its fidelity to source, Freedom at Midnight's biggest blind spot remains its riot sequences. Critics had pointed out how, despite the supposedly neutralising use of black-and-white, the show's depiction of violence remained skewed against a single community. In Season 2, there is a scene where Gandhi's car is pelted with stones upon his arrival in Calcutta on August 13, 1947. Yet, we never see the miscreants. This is not the case in the book, where the aggressors are clearly identified.

"It's not about me not wanting to show it," contends Advani. "You can tell the locality that has been destroyed is Muslim. The slogans being shouted are in plain Bengali (spoken by Hindus). Furthermore, in historical accounts, when Gandhi's grand-nieces Abha and Manu were asked about the attack, they said they did not see who did it and where it came from."

Advani denies charges of dialling down majority aggression, a pattern of willful evasion observed in recent historical dramas. "In Season 1, the violence of Direct Action Day was shown as a combination of both communities. One took off and then the other took off in retaliation. In Bihar, we show the 100 bodies which were all Muslim. There was a cycle of retribution that started after the League and Jinnah's aggravations. "

Season 2 culminates with a tense buildup to the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. However, instead of Nathuram Godse, the conspiracy to kill the Mahatma is relayed from the perspective of a lesser-known figure — Madan Lal Pahwa, a Punjabi refugee who unsuccessfully threw a bomb at a prayer meeting at Birla House on January 20, 1948, ten days before Gandhi was eventually assassinated by Godse.

"The world already knows who killed Gandhi. Wherever one may stand politically, the facts are undeniable. I did not want to give a figure like Godse the platform of my show. In fact, he stays out of the focus in the scene of the assassination. You just see his gun, the instrument that was used to kill the Mahatma."

Advani's next series, Revolutionaries, slated to stream on Prime Video, is a tonal about-turn from Freedom at Midnight. Adapted from Sanjeev Sanyal's book on armed revolutionary movements against the Raj, the series is a grand action epic spanning continents.

"It's about young, audacious revolutionaries like Rash Bihari Bose and Sachindra Nath Sanyal who took up the gun to overthrow the British," Advani says. "I am directing full-scale action after a long time. But the show is much more than that. These boys were extremely well-read and academic. There are beautiful nuggets about the Irish revolution and the intellectual and literary movements of that time."

This, Advani confirms, will be his last historical for a good while. Revolutionaries, if successful, might get a second season, while the curtains have surely fallen on Freedom at Midnight.

"I am historied-out," he chuckles.