Suggested Topics :

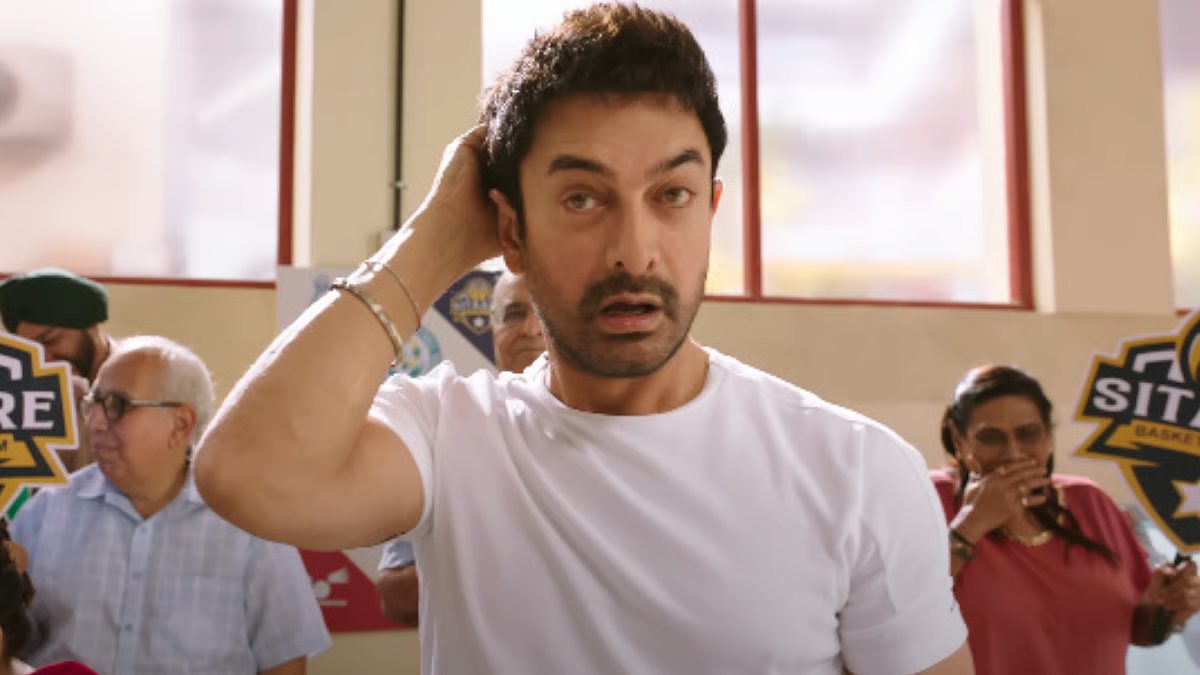

‘Sitaare Zameen Par’ Movie Review: Aamir Khan Wants Your Feelings

R.S. Prasanna and Aamir Khan’s remake of a Spanish sports dramedy is too preachy to be a classic underdog story.

Sitaare Zameen Par

THE BOTTOM LINE

A middling classroom experience at best.

Release date:Friday, June 20

Cast:Aamir Khan, Dolly Ahluwalia, Gurpal Singh, Genelia Deshmukh, Simran Mangeshkar, Aayush Bhansali, Samvit Desai, Rishabh Jain, Ashish Pendse, Rishi Shahani, Naman Misra, Vedant Sharma, Aroush Datta, Gopi Krishnan Varma

Director:R.S. Prasanna

Screenwriter:Divy Nidhi Sharma

Duration:2 hours 38 minutes

The nostalgia of Aamir Khan is hard to resist. He’s a one-man publicity machine. He resists streaming models. He bats for the theatrical experience. He is open about his failures and flaws. In an age of jingoistic fervour, bloated superstar spectacles and franchise cashgrabs, he produces and acts in a modest sports dramedy about a wayward basketball coach training a team of neurodivergent players (played, for once, by neurodivergent performers) for a national tournament. There’s no meta hero-entry shot; it’s just his character, Gulshan, matter-of-factly parking his car outside a stadium. He plays an unlikable man who isn’t afraid to look ordinary. In an industry ripe with hypermasculinity and vanity, he pokes fun at his own height and physicality — Gulshan is trolled as a “tingu” (shorty), even by his mom. He leads an old-fashioned remake full of newcomers and youngsters. And he’s an underdog after being ahead of the curve for years.

But the thing about nostalgia is that it often conceals a hesitance to evolve. Despite the dire state of mainstream Hindi cinema, staying static is not the same as staying rooted. Sitaare Zameen Par is the kind of movie that does the bare minimum because it knows it’s going to be judged as a sepia-tinted throwback at a time when being dated is almost a virtue. It also knows that its execution is secondary to its intent. A remake of a 2018 Spanish film called Champions, this spiritual successor of Taare Zameen Par (2007) is simplistic to a fault. The infotainment tone is not new, but for a film whose tagline is “everyone has their own normal,” the gaze itself is oddly ableist. Each of the Down Syndrome and Autism-afflicted members of the team has a quirk that is passed off as humour. There are times when we can’t tell if they’re supposed to be amusing or Gulshan’s ignorant view of them is supposed to be amusing.

I get that the writing aims to show us the mirror for reducing them to their conditions, but the lines are blurred. The middle ground is uncomfortable. Each of these characters is also given a sad backstory of sorts, as if to further spotlight their disability in a discriminatory society. This does the opposite of normalising them. Even within this subconscious subgenre of speaking from a space of condescension, it’s not inventive enough. Most of all, the film isn’t about the Sitaare (stars); it’s still about the Sitaara (star). It revolves around Gulshan’s transformation through the medium of this team — a problematic Delhi man-child sees the light during his 3 months of community service as their coach. They exist to redeem him. “I am not their coach, they are my coach,” he concludes, lest we dare to draw our own conclusions.

All of which is to say: Khan’s Gulshan is the elephant in the room. In successful social entertainers — particularly the vintage Rajkumar Hirani ones (3 Idiots, PK) — the strings were always visible; it was the puppeteering that was enjoyable to watch. But in Sitaare Zameen Par, it’s all strings. This might have worked if, like in the Munna Bhai movies, the staging itself is the message. Here, Gulshan always looks like he’s pretending to be a jerk so he can be schooled and we can be schooled. It’s like he’s blatantly being the setup to become the punchline. Remember the Munna Bhai M.B.B.S. (2003) scene where Munna and gang simulate an entire carrom session in the hospital ward to lift an old Parsi man out of depression? The audience was in on their little scheme. The whole of Sitaare Zameen Par feels like that scene, except it’s the performer who’s pretending and not the character. The country is that old Parsi man.

Gulshan’s personality is curated to turn every moment into an answer. He flings his hands up in exasperation so often that he looks like a dad play-acting to summon a reaction from his children (us). You can tell that he says something offensive — things like “paagal” or “mental” or “moms don’t have lives” — so that he can immediately be corrected. The chastiser is either his exceedingly tolerant wife Suneeta (Genelia Deshmukh) or Sartar (Gurpal Singh), the wise old principal of the institute. Suneeta and Gulshan are on a break because she wants to have a baby and he doesn’t; trust an old-school movie to conflate a difficult husband’s defects with his reluctance to have a child. We learn — we always learn — his issues stem from his father abandoning the family, and naturally, the team brings out his paternal instincts. Sartar’s scenes are limited to educating Gulshan about the students. Gulshan mutters something mean (or asks: “their families must find it tough, no?”), he responds patiently, rinse, repeat. I almost expected Sartar to be revealed as a genie, a Santa Claus-coded figment of Gulshan’s stunted imagination.

It’s a template designed for a generation that would rather tag an AI chatbot on X (formerly Twitter) than nourish their own curiosity and feelings. Most expressions and lines in the film seem like a direct result of a viewer’s invisible prompt: Grok, please explain. When Gulshan gets emotional towards the end, the voice in my head went: Grok, is this true? When he mansplains his own awakening to Suneeta, the screen that separates the film from its audience is incidental; he’s not breaking the fourth wall, he's guilting it into breaking. Much of the 160-minute film features Khan’s trademark Epiphany-face (or e-face) — the one where his character discovers or realises something big. Think of Bhuvan’s reaction when he accidentally notices Kachra’s ability to spin the ball in Lagaan. Or Akash when he realises he’s in love during the opera performance in Dil Chahta Hai. Or Dev when he suddenly realises that Priya ghosted him because she lost her legs in Mann. Gulshan goes “acha?” (is that so?) frequently enough to flatten the film into a series of noble, no-smoking-like disclaimers.

The few effective pieces are the ones that spoof the e-face — like an aquaphobic but animal-loving student unwittingly having a bath while trying to rescue a drowning mouse; or Gulshan unable to process that his mother might have a boyfriend. It’s the equivalent of the frame going black and white when the camera enters Raju Rastogi’s ‘poor’ household in 3 Idiots. But these moments are the exceptions, not the norm (I’m afraid to write “norm” because someone could pop up and humble me for enforcing my normal on theirs). There’s also the small matter of the sport itself getting lost in all the lessons. The point is to show that the game is just a metaphor for life, but it’s never clear how the team keeps winning despite Gulshan’s struggle to train them. There is no improvement arc; most of the action is confined to Gulshan’s colourful experience as a coach. They go from 0 to 100 across musical montages that refuse to offer evidence.

The writing remains predictable, which is fine (Laapataa Ladies weaponised the art of predictability), but it’s also lazy. The conflict emerges when the tournament final is in Mumbai and the gang can’t afford to travel. I like that the film doesn’t offer a serious solution to this — it goes goofy with Gulshan and Suneeta (and her failed acting ambitions), but it doesn’t have enough fun with the track. It’s almost a bit scared to go full-comedy because then it might be accused of trivialising the subject. The second half opens with a scene in which Suneeta’s ‘eccentric’ Parsi employee buys an old vanity van and parks it outside her shop. It’s such a random thing that you immediately know this van will become the team’s unofficial bus. Right on cue, the team creates chaos on a DTC bus and gets thrown out by insensitive North Indian passengers who insist that there should be separate buses for “these people”. It’s like the film consistently chooses the easiest setup without any dressing. You can see the conceit coming from so far away that, forget spoon-feeding, the viewer is compelled to swallow the plate as well.

On a personal note, Sitaare Zameen Par is one of the rare screenings I entered with my fingers crossed. Somehow, given the circumstances, and given what Aamir Khan means today, the stakes felt high. It’s impossible not to root for the movie within the broader landscape of Bollywood. Even as a film critic: or perhaps, especially as a film critic. I found myself hoping to be moved, as I was for much of Laal Singh Chaddha and Secret Superstar. Formula done well, I chanted. If this meant being the same student that Gulshan, his team and every adult in the film becomes, so be it. I was always a solid student, even when the teacher was dull. The song ‘Papa Don’t Preach’ rang in my head. I was ready. What followed was not disappointment, but heartache. The kind you feel when the player you always secretly liked implodes in yet another semifinal.

Sometimes, though, you want to feel so desperately that you start to latch onto the smallest signs of life. A one-liner, a slow-mo basket, a reaction shot, an instrumental passage in a song. For example, when a sheepish Gulshan spots the judge that sentenced him at their game — she’s the aunt of a team member — he stops berating the player and starts mollycoddling him loudly. His switch provides a fleeting glimpse of ‘90s Aamir Khan: the voice inflections, the chuckle, the wide eyes and tongue-twitching. For once, Gulshan is actually pretending. I willed myself into laughter here, like a famished rodent feeding on sunbaked scraps. The scene wasn’t that great. But the hall around me had already erupted, presumably in the same pursuit of family-friendly solidarity. If you’re determined to have a good time, not even the film can come in the way. I could hear a silent prompt echo towards the screen: Grok, is this funny?