Suggested Topics :

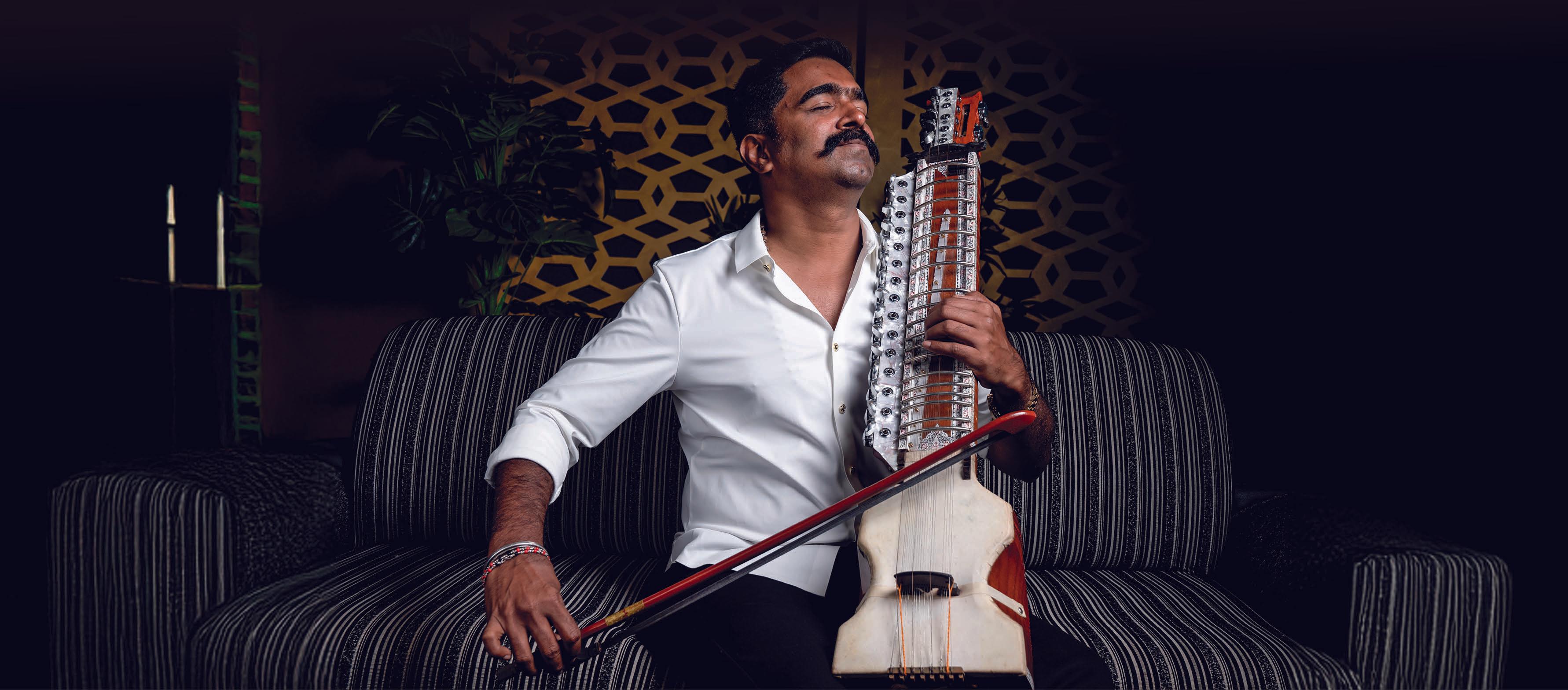

Ravi Basrur's Musical Alchemy: On 'KGF,' 'Marco' and The Rajinikanth Dialogue That Always Grounds Him

Ravi Basrur, the 'KGF' maestro, hammers hits from Basrur, his village in Karnataka. Inspired by Yakshagana beats and blacksmith sounds, he crafts blockbusters and directs heartfelt films rooted in passion.

Ravi Basrur’s pulsating background scores last year for the Malayalam blockbuster Marco and Kannada superhit Bhairathi Ranagal might be the flavour of the moment, but what plays constantly in his head and heart are the sounds of metal being beaten by his artisan father and the drums that serenaded him as a child in the village of Basrur in the Kundapura taluka of Udupi district in Karnataka.

“When you grow up on this coast of Karnataka, you will imbibe the rhythmic, hypnotizing tala-maddale (verbal, rhythmic, musical exploration of a story through debate), Yakshagana (a classical-folk dance form of Karnataka with songs and colorful costumes), and Kola (ritualistic performance devoted to family deities) somewhere, somehow. Then, there are the bhajans that continue to play from the nearby temples. All of them are inside of me, and I believe my music is born from that space. I have not learned music formally. It is these padas, songs that influence me to create a tune.”

Then, there is the small workshop of his father. “Initially, I heard the sound of iron, then sheet metal, then gold, the sound that is created when the hammer strikes each is unique. Those are a part of me too.” Incidentally, during the COVID-19 lockdown, Basrur was in his hometown, helping his father at the blacksmithery.

When the Unni Mukundan-starrer Marco came to him, it was a small film. “They showed me the footage. I instinctively felt it should bear no shade of my regular music and said we would use new software, and it worked,” says Basrur.

Also Read | Films To Watch In 2025: Yash's 'Toxic' And Salman Khan's 'Sikandar' To Rajinikanth's 'Coolie' And Kamal Haasan's 'Thug Life'

In an hour-long conversation over the phone from his village, where he has established the massive Ravi Basrur Music and Movies Studio on an acre of land surrounded by coconut groves, the usually reluctant interviewee travels back in time and back to the present, to place his music and life in context.

THR: Do you remember when you realised you had a flair for music?

Ravi Basrur: In impromptu competitions we had in our area, we would create music from the steel plates we used to eat from. But I did not give it any more importance than a passing hobby. Music was a part of our lives in the village, and I had no idea it would become my profession and transform my life and that of my family.

Looking back, I do remember a grandfather who made violins, and another who played the panchavadhya (five instruments). So, probably this life of mine was meant to be.

[Note: Trigger warning — mentions of self-harm, suicide.]

You’ve rarely spoken about your origin story.

RB: The age between 17 and 21 is full of trauma. You have to take decisions without the wisdom to think them through. Driven by multiple small loans as small as ₹85 and ₹350, I decided to donate my kidney and pay off my loans. I went to Mangalore without informing anyone, signed the papers, and was lying alone in a room before surgery. I suddenly realised anything could happen to me. I ran out and spent three days in the Mangalore bus stand.

Also Read | Vijay’s Final Film ‘Jana Nayagan’ to Release in January 2026

I saw an orchestra van (Shad’s Music World, run by Naushad) and requested the owner to allow me to play for three shows. I thought I would use that money to go to Bangalore. There was more horror waiting. I was kicked out of the place I was staying at in Bangalore and decided that would be my last day.

By chance, one Mr. Kamath, who gave me sculpting work on sheet metal, found me sitting anxiously near West of Chord Road and took me to meet someone in the field of jewellery. He told him I was a good worker and would set diamonds well but was overly fond of music. The gentleman began speaking, and in my hunger—I’d not eaten for three days—I told him to give me money for food and then speak. I came back after eating chitranna (mixed rice). He told me that I had great things in store. People had always told me that, and for some reason, I snapped, because nothing in life was positive. I told him to give me ₹35,000 if he thought I would become a big man so I could buy a keyboard. He did not think for a second. He told me I did not have to return the money.

That day, Kiran from Basrur changed his name to Ravi Basrur in honour of the man who gave him a second life and the village that birthed him. What happened next was nothing short of a miracle. I think of these human gods every day and worship them from a distance.

[Trigger warning ends.]

Also Read | Mohanlal and Prithviraj Talk Violence in Malayalam Cinema: On 'L2: Empuraan' and 'Marco'

THR: You’re someone who has forged deep bonds in the industry, working with the same directors, usually from their first film. How do these sustain in these fragile times?

RB: Let me put it this way: With most, I’ve walked with them from the first step. Sometimes, these are relationships formed by chance. I worked as a music producer for 63 films and was part of Prashanth Neel’s Ugramm (2014) in that capacity when he told me to compose. It was an unexpected gift after 10 years in the industry. It is like magic, that bond. Something similar happened with Narthan in Mufti (2017) and its prequel Bhairathi Ranagal. More recently, I felt that connect with the Marco team, with Singham Again (2024). Of course, with KGF (2018, 2022) and Salaar (2023). It is teamwork. And like Prashanth says, “On that day of recording, give every drop of your potential to the film.” I’ve seen what he’s gone through to make his movies.

THR: What does this mammoth success mean to you?

RB: Ondhu hothina oota. One single meal. That’s what this success means to me. We linger on in the field for the love of music. Success is something that might or might not happen. It is not the goal.

I don’t take credit for anything after a movie is made. It is not ours after that. I am often reminded of Rajinikanth sir’s dialogue: “Close your ears and mouth. Because only when you hear rubbish will you want to retaliate.”

When I entered the industry, all I had access to was a 12-by-12-foot room or a 15-by-15-foot one. That’s all I craved, and I made the music that brought me here, from there.

Read More | Allu Arjun to Collaborate With Atlee, Trivikram Srinivas Before Returning to 'Pushpa' Franchise

THR: You’re now known for your music in tentpole films, films that are mounted on a scale. Do you miss composing songs for regular films, or simple tunes?

RB: If you look at my discography before KGF, you will find many emotional, soft songs. But even now, I try to push in these numbers. Even in a film like Marco, you have the lilting “Udal Paadhi.” And, I continue composing for regular films, so there’s no question of missing something.

THR: Have you ever tried to analyse your music or why it clicks?

RB: No. Because, honestly, I believe I am not talented. I’ve not formally learned music. This is some God-given gift. If something is destined to be mine, it comes my way. There are so many others who can compose like me. Why should I be given a particular movie? I liken myself to a tap—music flows through me.

I composed a song in Kundapura Kannada (a dialect) and it was lying unused. I ended up using it for Salaar six years after it was composed. “Sooreede” was meant to go to Prabhas, that’s the only way to see it.

THR: You have a spiritual bent of mind and approach life philosophically, right?

RB: Most definitely. We use the pre-existing seven swaras in permutations and combinations. I’ve been speaking to you without any prompt for an hour now. Don’t you think the human ability to think and speak is bigger than AI? I am a believer and am not being immodest when I say that what I have heard is what emerges out of me, with a little bit of my idea of music.

No one can claim to be an original, except probably someone who cannot see and hear—their thought and imagination will be original. Else, we are all influenced by something or someone.

Also Read | Casting the Net Wide: How Casting Directors in India Are Changing the Game

THR: Is that why you avoid listening to songs now?

RB: Yes. I don’t listen to anything and request my team to not bring anything to my notice. I’ve been given a chance to serve music and I have to do it honestly.

But, yes, growing up, I used to listen to music. We had a radio that we tuned, and it would play Hindi songs. Later, when television happened, we would wait for Chitramala to listen to the rare Kannada song on it. My favorite used to be the composer Hamsalekha. When traveling to Bangalore, we would play it through the route. How can I forget the impact of songs from his Premaloka (1987)?

Life was nicer with fewer choices. Now it’s like a veritable buffet and nothing meets our expectations, nothing gives unbridled joy.

THR: How important are lyrics to you?

RB: I cannot compose without lyrics. That’s my drawback. I need at least dummy lyrics. And so, most of the time, I am given lyrics and I then work with the director, understand the tempo, and come up with a tune. Somehow, I feel that when you listen to a song, you should know its root, and lyrics are the root.

THR: Does fame sit on you easily?

RB: I run far away from labels. I believe the crown should be in the hand, not on the head. Only then will you know its weight. I pray I never wear that crown.

Read More | 'Item' Numbers in 2025: The Hook Step, the Gaze and the Influence of Instagram Reels

THR: For the outsider, you’re someone who made it big after leaving home early. How do you deal with people who look up to that as inspiration?

RB: Bombay taught me a lesson no other city can—you can survive with even ₹10. It also taught me to think before taking up something. If you do something without thought and it does not work out, plumb the depths before giving up and moving on.

Every two or three days, I see so many young boys from other cities show up at the studio, hoping to make it big. I give them all a half-hour lecture, tell them about my life, what I went through in a new city, and request them to think before making any decision.

I began an orchestra in class 8, became an orchestra singer, learned to play the keyboard in 12 days. We did not have a harmonium at home, and I got access to it when the bhajan group would spare it for a few hours. At home, using a slate and a pencil, I’d draw the keyboard and practice.

I went to Bangalore to become a dancer. I did not. Till Ugramm, all I faced was failure after failure. And no one who sees me now knows that I had a low phase too.

THR: You also sing for other composers, including A.R. Rahman?

RB: I have, yes, but if I sense the texture of my voice does not suit the song, I’m the first to request them to use someone else.

THR: You have said you’re a work-in-progress, working on yourself?

RB: Yes, I observe people. A lot. And if I see a trait that I believe is good, I tend to pick it up. If it suits my personality, I keep it. Else, I let go.

For example, I deeply admire Appu sir’s (the late Puneeth Rajkumar’s) simplicity. I carry that with me. Yash’s dedication is deeply inspiring. He saw where he would be, even when working in TV serials. He invested in creating today’s Yash.

From Prashanth, I’ve learned to never speak ill of anyone. I’ve known him since 2009, and except cinema, he does not speak about anything else. Not about anyone else’s movies, not about people, nothing. That’s why he is where he is.

Read More | Thaman Explains Why 'Game Changer' Album Didn't Work: None Of The Songs Had a Proper 'Hook Step'

THR: What’s your one indulgence?

RB: Once a year, I try to make a movie. About 30 people are part of my team. I have always loved direction. Once I became financially strong, I decided to devote three months of time to make a movie on a limited budget. I even turned hero for one.

What I make in films, I give back to it. Now we have our own camera set-up, lighting gig, and edit suite in our Basrur campus spread across an acre. I split my time between here and Bengaluru.

So far, I’ve made Gargar Mandala (2014), Bilindar (2016), Kataka (2017), Girmit (2019), and Kadal (2023). Up next is my 12-year dream project, Veera Chandrahasa, a film about Karnataka’s heritage. Post-production work is complete, and we are planning to release it soon.

To read more exclusive stories from The Hollywood Reporter India's February 2025 print issue, pick up a copy of the magazine from your nearest book store or newspaper stand

To buy the digital issue of the magazine, please click here.